With the coronavirus pandemic looming over the election, including evidence of a new surge, most states are handling an historic level of voting before the official Election Day on Nov. 3.

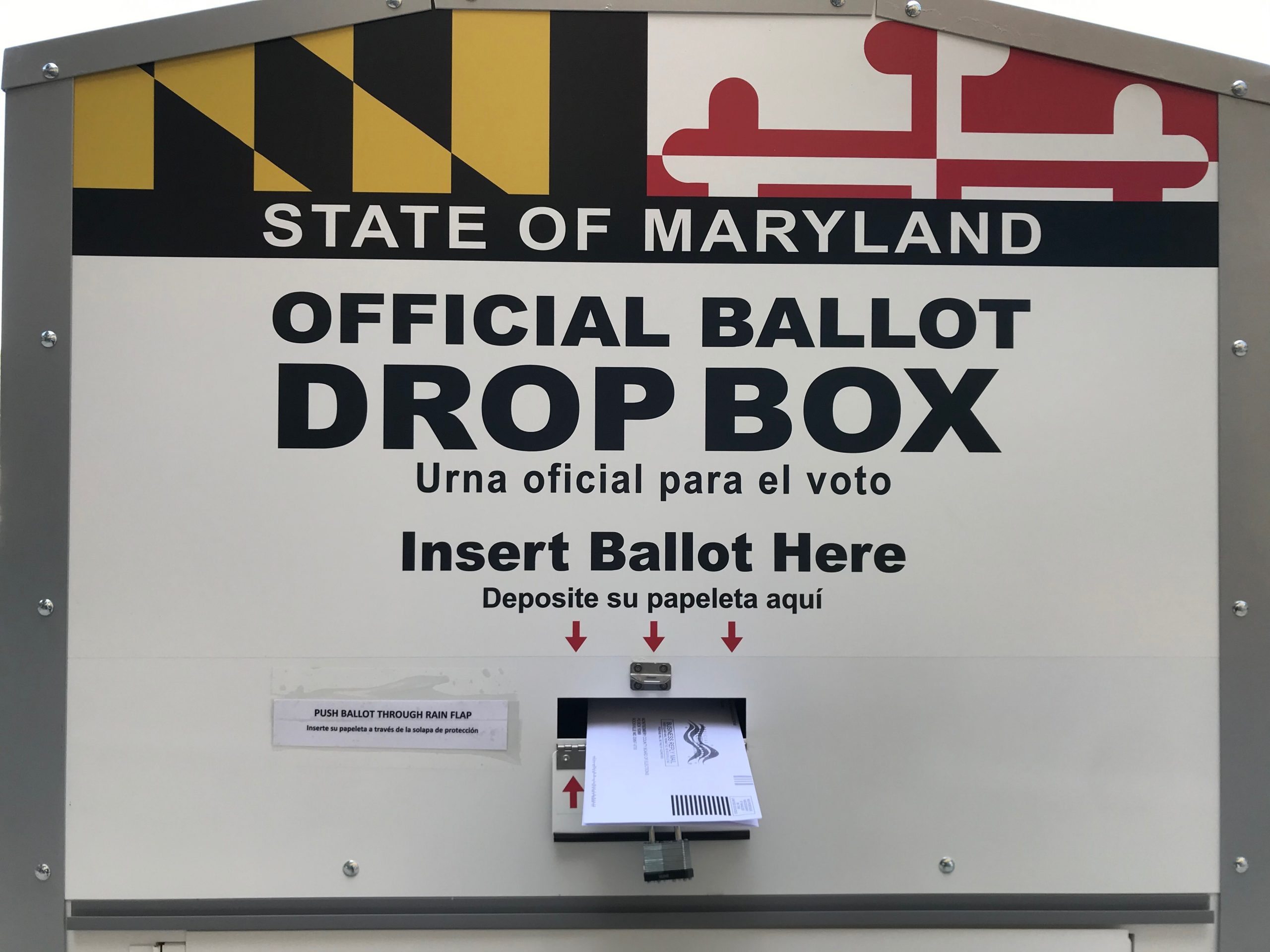

Voters who choose to vote early are returning their ballots by mail, or dropping them off in person at local election offices or various secure drop-off boxes if their states allow them to do so.

However, the methods by which voters are casting ballots appear to depend on which candidate they favor: 60% of President Donald Trump’s supporters were planning to vote in person on Election Day, compared to 58% of Joe Biden’s supporters planning to vote entirely by mail, according to the Pew Research Center.

However, many Republican-leaning states have few or no ballot drop boxes. Early voters instead have been instructed to drop their ballots off at, in some cases, a single location per county.

“With strict absentee voting deadlines, mail delays, and limited choices for returning ballots, voters could face no alternative but to vote in person,” said Raul Macias in an analysis for the Brennan Center for Justice, where he serves as counsel in the Democracy Program. “However, many voters requested absentee ballots precisely because they have concerns about voting in person. These voters could be forced to choose between their vote and their health.”

Three states — Mississippi, Tennessee and Missouri — don’t allow voters to drop off their ballots in person by any means.

North Carolina, meanwhile, is the only battleground state that did not deploy any ballot drop-off boxes. In the Trump win column in 2016, the state this year is relying on its 100 county election offices to serve as drop-off locations for its 10.5 million residents, which is nearly one location per 100,000 residents.

Pennsylvania, another battleground state that was won by Trump four years ago, faced a lawsuit filed by the president’s campaign to prohibit the state from using ballot drop boxes. But on Oct. 10, a U.S. District Court ruled that the campaign failed to prove that voter fraud is “certainly impending” with the use of drop boxes.

With that suit no longer a barrier, Pennsylvania is using 143 ballot drop boxes across the state. This is on average over two locations per county. Larger and more populated counties, such as Philadelphia County, have up to three — and, on average, over one per 100,000 residents.

Other Republican-leaning states, or those with Republican governors, also have decided to use only election offices as drop-off sites and not to install drop boxes. Those states include Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, New Hampshire, Oklahoma, South Carolina and West Virginia, according to a FiveThirtyEight guide.

Officials in Texas and Ohio recently came under fire for trying to restrict ballot drop boxes to one per county. After conflicting rulings by several courts and legal back-and-forth, confusion remains.

Although a federal judge initially blocked Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s order restricting ballot drop-off locations to one per county from taking effect, a federal court has since upheld the restriction in a ruling last week.

But in a separate case in state court, a different judge on Oct. 15 struck down the order. The state has appealed the ruling, which means the original directive will stand for now until there is another ruling.

Caleb Jackson, an attorney on the federal case, called Abbott’s order “ridiculous.”

“We hoped that we would get the win and that the win would stand, but for now the win does not stand,” said Jackson, a voting rights attorney for the Campaign Legal Center, a nonpartisan group. “So unfortunately, Texas voters, because of their governor, are forced to use a burdensome system in order to cast their vote.”

Similarly in Ohio, several legal challenges have been mounted against Secretary of State Frank La Rose’s move to leave in place a May emergency coronavirus plan for one ballot drop-off location per county, used in the primary, for the general election.

La Rose contradicted his own rule by allowing Cuyahoga County — which includes Cleveland and is the second most-populated county in the state — to set up an additional drop box across the street from the election office.

He then released a statement earlier this month saying his order never prohibited counties from confining the location of ballot drop boxes to county property. But at the same time, La Rose rejected Cuyahoga County’s plan to install more drop boxes at six public libraries.

A federal judge initially dismissed the lawsuit brought by a civil rights group in late September. On Oct. 9, following an appeal to reconsider the case, the judge again allowed La Rose’s directive to stand.

With less than two weeks to Election Day, it is unclear where and how many ballot boxes will actually be in place in Ohio.

Even if groups in Ohio or Texas bring their cases to the Supreme Court, which would be the next step, it is unlikely that they will be heard and ruled upon in time, especially as the early voting period in both states has begun.

In accordance with Texas’ one-box-per-county rule, and if Ohio follows a similar plan with one extra location in Cuyahoga County, the two states will have 254 and 89 ballot drop boxes, respectively.

This is, on average, less than one ballot box per 100,000 residents. In comparison, Maryland, a Democratic-leaning state with nearly half of Ohio’s population and not even a quarter of that of Texas, has nearly 5 ballot drop boxes per 100,000 residents.

Herb Asher, professor emeritus of political science at Ohio State University, told Capital News Service the restrictions on the number of ballot drop boxes is not a “key issue,” as Ohio offers other means of voting.

But he called Trump’s efforts to undermine the United States Postal Service, which led to some public distrust in mail-in voting, “a sin.”

“If you didn’t have a single ballot box, you’d still have, you know, hundreds of mailboxes, you could mail it back,” Asher said. But he said he understands that people are “nervous about this because of the president’s attacks on the postal service.”

“I think it was a deliberate attempt on the president’s part to reduce turnout or make it less likely that people will vote,” he said.

However, other experts say restrictions on the number of ballot drop boxes are themselves a form of voter suppression that is especially consequential in counties and cities that are heavily populated and have large minority populations.

“If you have a county that isn’t that large geographically and only has 500 people…the order doesn’t have any effect,” Jackson, a Texas native, said.

“But,” he added, “when we’re talking about Harris County (Houston), Travis County (Austin), Fort Bend (County in suburban Houston), which are not only huge, they’re also…more diverse than the state…and in reality, far more blue than the rest of the state, I think that it’s pretty clear what Governor Abbott was trying to do, which is suppress votes and make it harder for voters in those counties to vote.”

Texas’s most populous county, Harris County, had initially planned to have 11 drop box locations but it does not plan to reopen them amid the legal dispute, a spokeswoman told CNN. This will leave its 4.7 million residents with only 1 location. About 44 percent of the county population is Latino or Hispanic, and 20 percent is Black.

Similarly, the 1.3 million residents of Franklin County, Ohio, which includes Columbus, will share one drop box location. The county’s population is 23.8% Black and 5.8% Latino or Hispanic.

The heavily Democratic state of New York also decided not to install any ballot drop boxes, according to Newsday, a move that is especially consequential in New York City.

With the 88 early-voting centers only accessible after Oct. 24, the city’s population of 8.3 million, largely composed of people of color, have had to visit one of five election offices — one per borough — if they wanted to drop off their ballots before the early voting period begins.

“This is not just a partisan issue,” Jackson said. “Voter access is an issue that should not be dependent on who’s a Republican and who’s a Democrat. Both parties should try to make it as easy for all eligible voters to vote as possible.”

With a record early voting turnout — over 45 million so far, according to the University of Florida’s U.S. Elections Project — it doesn’t seem that voters are deterred by the suppressive measures, Jackson said.

“I think people are seeing what’s happening,” Jackson said. “They’re seeing what Governor Abbott and what politicians and other states have been doing, and (see that) if they’re doing all of this, then there must be a real reason they need to vote…Their vote really must count.”