Many pollsters expect record-breaking voter turnout for this year’s presidential election, but there are still many people who cannot or will not cast a ballot.

Voter turnout among adults in the United States has not topped 60% since 1968. Nonvoters tend to be younger, less educated, less wealthy and less likely to be white than voters, as disadvantaged communities are more likely to be disillusioned with voting and to face numerous barriers to access, studies have found.

Nonvoters are the number one topic in this election, said David Paleologos, director of Suffolk University’s Political Research Center.

That’s because so many other people are voting who usually don’t.

Paleologos said high voter turnout is usually due to high-quality candidates that generate excitement, but not this time around. Instead, he told Capital News Service, President Donald Trump “will probably be responsible for driving the highest turnout the country’s ever seen,” which he expects will favor former Vice President Joe Biden.

“You’ve got people who have been on the sidelines in the political process, and they’re going to either validate (Trump) in his last four years, or they’re going to vote him out,” Paleologos said.

Some will remain on those sidelines, including Jesus Figueroa of Arkansas and Peter Vigil of New Mexico, who are among 5 million people who are disenfranchised due to felony convictions. Because of systemic racism, this especially impacts Black Americans, with one out of 16 adults disenfranchised due to past felony convictions, according to an estimation by the Sentencing Project, which is a Washington-based, nonpartisan organization that advocates for a more equitable justice system.

“Honestly, it kind of feels dehumanizing,” Figueroa said in an interview. “You’re free but you’re still locked away from enjoying the basic rights of being an American.”

Vigil said: “There’s no reason why they should withhold your right to vote, because you’re not hurting anybody by voting, and you’re actually helping the process.”

Additionally, there are over 20 million immigrants in the United States who cannot vote because they are not citizens, including those with permanent legal status with green cards.

Jessica Schonhut-Stasik, a green card holder studying astronomy in Hawaii, said “if I had the opportunity, I would vote with my whole heart,” but she worries about those who would still be left behind.

Schonhut-Stasik said that the process to get a green card was very difficult and expensive, and that being British, white and surrounded by a supportive academic community, she said she knows it is far more difficult for most other immigrants, ”the ones who need policy that’s on their side the most.”

Mexico is the largest country of origin for lawful immigrants, but Mexicans are disproportionately unlikely to be granted citizenship, according to the Pew Research Center.

Then there’s voter suppression, which Allan Lichtman, distinguished professor of history at American University, said “in part results from one of the Framers’ biggest mistakes, and that is there is no constitutional right to vote.”

Amendments that have expanded voting rights identify reasons that states cannot take those rights away, eliminating “the most blatant forms of discrimination,” Lichtman said. But “new, more subtle forms of discrimination have come into effect,” often falling “most heavily upon minorities,” he added.

These forms of voter suppression include voter ID laws, which disproportionately impact Black Americans in many states. Black Americans also face longer lines at the polls on average, and are more likely to have their ballots rejected.

Lichtman says an amendment affirming the right to vote for all Americans “is critical,” and “certainly would have both practical and inspirational effects.”

Language barriers, disability, lack of time to learn about candidates or to vote, and confusing policies or paperwork also disproportionately impact disadvantaged communities and decrease voter turnout. Generational factors can compound the difficulty in overcoming these barriers, according to research by Rachael Cobb, professor of political science and legal studies at Suffolk University.

For those who have grown up in families or communities that generally do not vote, “you never get on the voter list, nobody pays attention to you, you’re not part of a network of people who are voting,” Cobb said.

“So the whole experience is in some ways alien to you,” Cobb said. “It’s an ignorant thing to say that (voting) is really easy.”

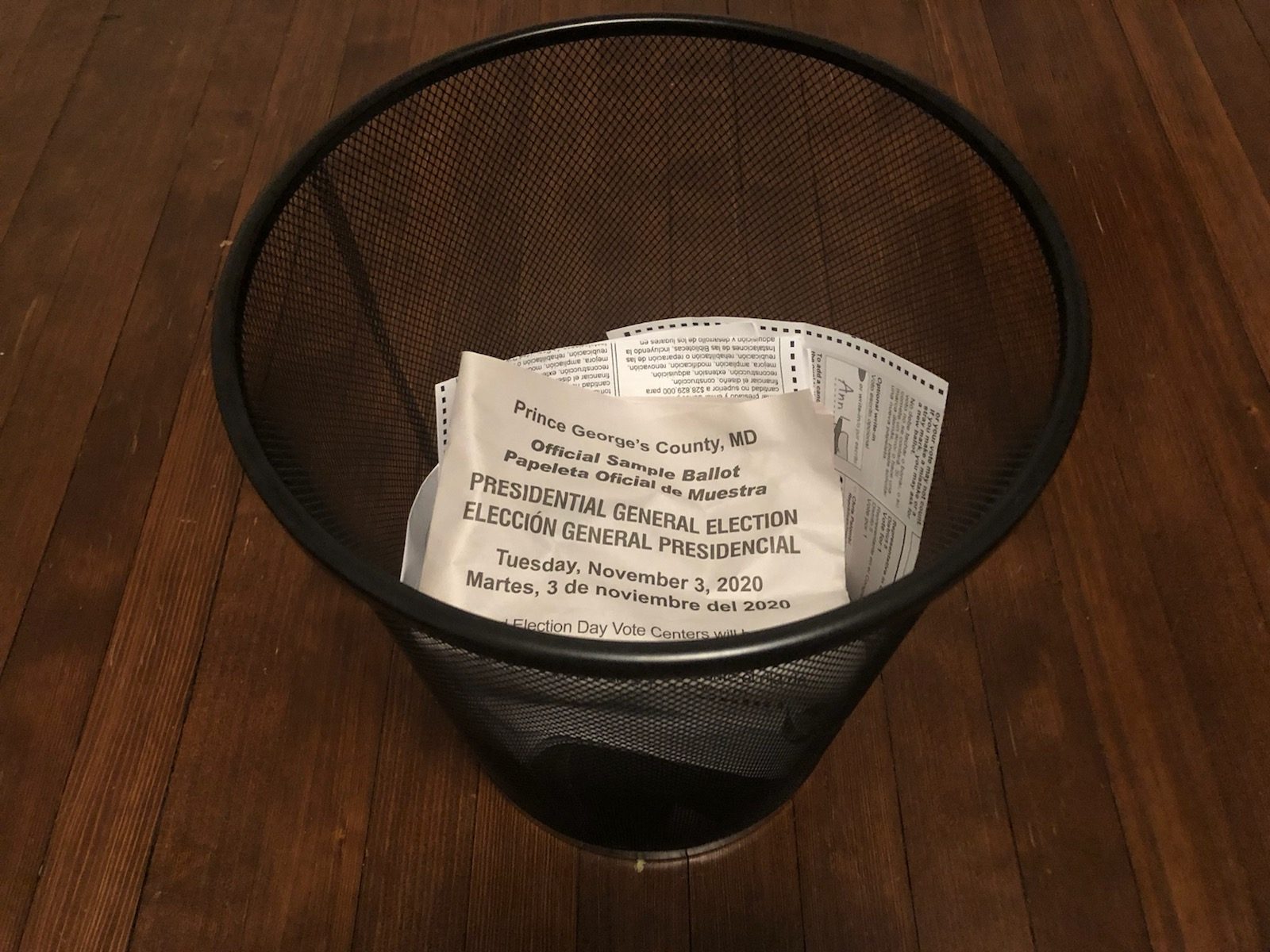

All of these barriers can contribute to a lack of faith in the electoral process, which is a major reason that people do not vote, according to a Knight Foundation survey of chronic nonvoters released in February.

Caitlin Donnelly, program manager of Nonprofit Vote, an organization that assists nonprofits in voter outreach efforts, said many people feel resentment toward elected officials that they perceive largely ignore them “until it’s election time.”

“They see all this attention showered upon them in the summer before an election, and then those people are gone the day after the election, and their issues aren’t tended to,” Donnelly said. “That can feel like, ‘What’s the point of voting?’”

Some people may abstain from voting to avoid participating in a political system they perceive to be broadly corrupt.

Ryan Rickard of Kansas City, Missouri, said he does not vote because he does not want to legitimize the United States government.

This year, he says he is sympathetic with those who want to vote Trump out, but – citing both candidates’ records on immigration, foreign policy and race – he said he doesn’t know that “Biden won’t be worse.”

“Those two men are bad people,” Rickard said. “We are being coerced into leaders that we do not want and forced to abide with their decisions.”

Rickard points out that voting has not been equally accessible to all throughout the nation’s history, and that today “we still can’t, in fact, ensure that everyone who wants a vote is given a voice.”

“All of this should give us pause that maybe there’s a better system,” Rickard said. “Something better out there.”

The majority of voters and nonvoters alike agree that in the United States “things have gotten on the wrong track,” according to the Knight report.