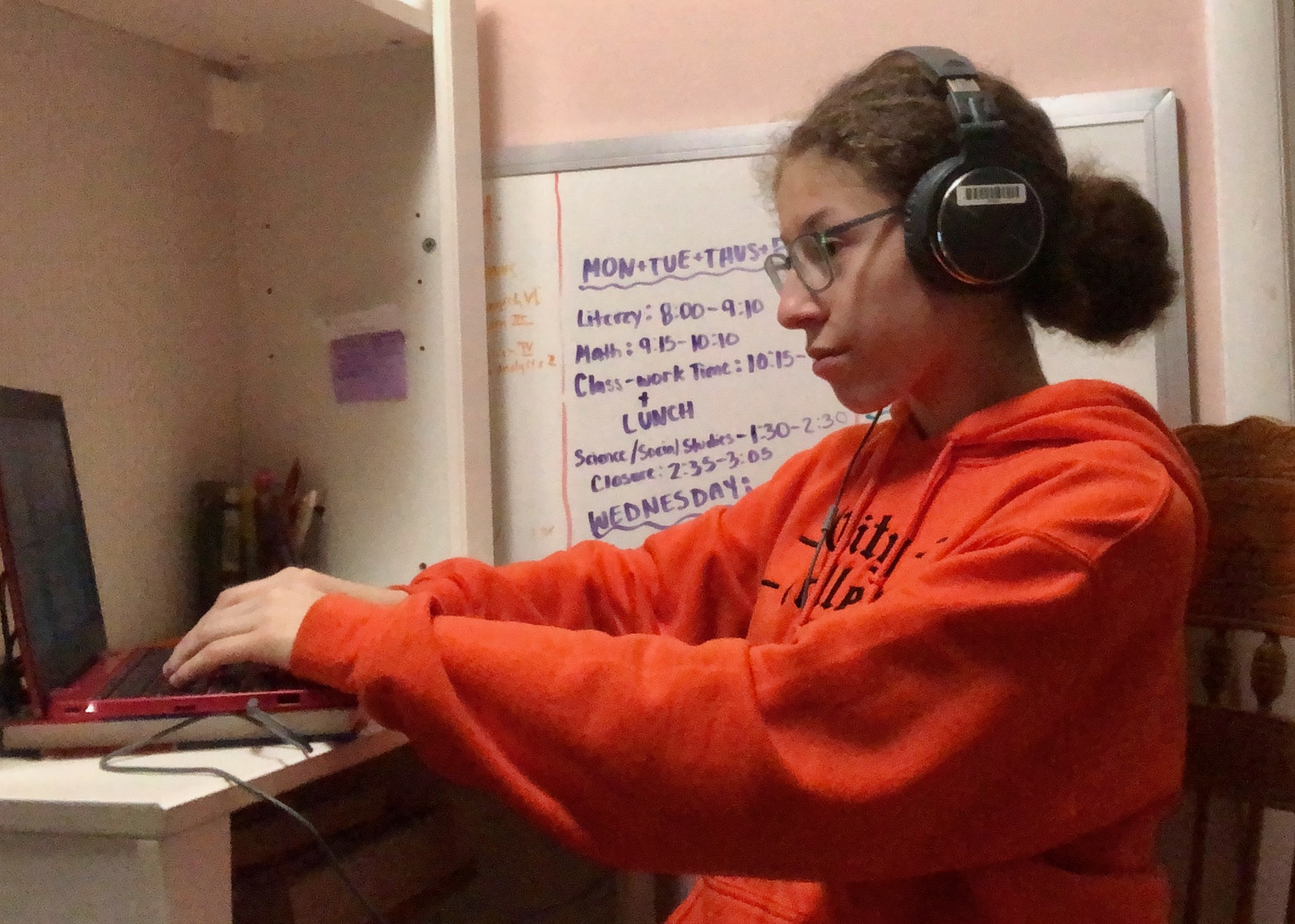

ANNAPOLIS, Md. — After Kimberly Vasquez’s two younger sisters log into their virtual classrooms from their Baltimore home, there’s barely enough bandwidth left for the high school senior to get into her class.

“It’s a constant conflict and battle, trying to get connected, trying to learn,” the 17-year-old Vasquez said.

Her family has Comcast Internet Essentials, a low-cost broadband plan for low-income households that promises no more than the Federal Communication Commission’s minimum bandwidth for high-speed internet. But FCC guidelines caution that if several users are on a network simultaneously, the bandwidth that Internet Essentials provides may not be sufficient for video streaming on multiple devices.

The college-bound student said watching her grades fall because of remote-learning obstacles is “heartbreaking” and makes her feel “like a failure.”

Across the state in rural Allegany County, the mountains on either side of Dawn Vanmeter’s home block a cell signal from reaching her family’s school-issued hotspot, a device the size of a cell phone that acts as a WiFi router.

So each day, Vanmeter stuffs a backpack with books, supplies, a computer and snacks before driving her two granddaughters, Abby, 8, and Ayedann, 10, just a few miles away to her son’s house atop a hill.

“He has better access to the cellphone tower than I do,” she said.

These families live in two of the most digitally disadvantaged parts of Maryland, and are just an example of the thousands of households who have lacked the equipment or the internet access to attend virtual school during the pandemic.

State officials since 2018 have been addressing rural access issues where broadband infrastructure does not yet exist. But lawmakers who say progress has been too slow are already earmarking legislation that would address statewide broadband access.

In both Baltimore City and Allegany County, the number of households without a broadband connection hovers around 40%, but usually not for the same reasons.

Allegany County residents are hamstrung by topography that blocks cell signals, and a population density too low to justify the investment of broadband providers.

In Baltimore, broadband infrastructure is plentiful. But urban connectivity often comes down to affordability, according to state officials and city stakeholders. Broadband capacity may also be a culprit.

The burden of the state’s digital deficit landed on the shoulders of school districts in March when schools transitioned to remote learning. And to keep children “in school,” officials across Maryland had to act fast to get computers and internet service to those without.

Still for some, the Vasquez sisters and Vanmeter’s granddaughters, the tools provided are inadequate to give them a virtual ride to school.

The chief information technology officer of Allegany County Public Schools, Nil Grove, said she and her team gave out 8,000 Chromebooks and 1,300 hotspots to families. But there were still students in the areas around Flintstone, Mount Savage and Old Town, where Vanmeter lives, who do not have the option of high-speed lines, and cannot get a signal through a hotspot.

“We tried with most every one of them,” Grove said. “We tried to see if ‘Oh, take the hotspot and put it in this window. Now let’s try it in your bathroom.’ ” But Grove said there was nothing more she could do for about 200 students.

At the end of September, the county bused approximately 25 unable-to-connect elementary and middle schoolers to Flintstone Elementary to use the building as an internet hub.

Vanmeter’s oldest granddaughter joined them. The students connected to virtual class from their socially distant desks in the school gymnasium. Weeks later, the county allowed a few grades at a time to begin hybrid learning, with teachers coming in person to lead classes.

But as COVID-19 cases spiked statewide in early November, Allegany County officials sent students back home, including Abby and Ayedann. Wednesday the county reported a case positivity rate of 13.22% — the highest in the state.

One Baltimore technology advocate said addressing the problem takes more data than just knowing where broadband exists and doesn’t exist; it’s about knowing how efficient it is for those who have it.

“There’s this voiced frustration from within communities that are saying, ‘We aren’t getting access. We aren’t getting connected, even when we have a connection,’ ” said Andrew Coy, the executive director of the Digital Harbor Foundation.

The former senior adviser to the Obama administration’s technology and innovation team said the standard minimum FCC delivery speeds internet service providers, like Comcast, boast are inadequate and need updating.

“These gaps are chasms, and they are going to have immediate and long-term health implications, educational implications, economic implications,” Coy said.

Kristie Fox, vice president of communications for Comcast’s Beltway Region, declined to be interviewed but wrote in an emailed statement: “The digital divide is a vast and complex problem that requires collaboration – with the school district, elected officials, nonprofit community partners, and other private-sector companies – so everyone is part of the solution.”

The state so far has invested $14 million in partial grants projected to expand rural broadband to 15,000 households through its Office of Rural Broadband. Gov. Larry Hogan, R, created the office by executive order in 2017 “to provide affordable high-speed internet service to every Maryland home by the year 2022.”

To get state funds, jurisdictions, cooperatives or neighborhoods partner with an internet service provider and raise half of the project’s funding through federal grants or in-kind donations. The office grants the funds for the other half.

Director Rick Gordon said that even though his office is “off to a good start,” challenges exist, like enticing service providers to expand into broadband deserts.

“I’m an engineer, given enough time and money, anything’s possible,” Gordon said. “The goal is to make sure that the time is managed and the money is being used appropriately to reach the end result.”

Still, he said, the office is on track to achieve their goal and to date the governor has given them the annual funds they’ve requested. Gordon said his initial cost projection was $100 million to get broadband to around 71,000 rural unserved households.

But that projection is based on an FCC definition that classifies “unserved households” as those without the infrastructure for download speeds above 25 Mbps. Census data shows that, in fact, nearly 200,000 households in rural counties lack a broadband connection, regardless of whether the infrastructure exists.

The office focuses on the 18 of Maryland’s 24 jurisdictions that are defined by state law as rural, and some rural portions of other counties. No similar state entity exists to tackle urban digital disparities. This year marked the first that the office directed funds into Baltimore in the form of federal pandemic relief grants.

Economist Alex Marré said it’s key for states to have a comprehensive approach because broadband provides rural and urban consumers similar economic benefits, like shopping for low-cost goods and accessing healthcare and education. But rural areas are just that much further disadvantaged when it comes to the internet because the infrastructure may not even exist in their area.

“Even if everybody could afford an internet subscription, there’s just not the fiber laid out there,” said Marré, who studies broadband infrastructure as a regional economist for the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond.

The COVID-19 pandemic, Marré said, has “really just driven home how broadband, which used to be thought of as kind of this luxury 10 years ago; I mean, it is a necessary utility today.”

Maryland lawmakers interviewed by Capital News Service agreed that a statewide solution is needed and that it’s time to start thinking about the internet as a necessity.

Allegany County Delegate Jason Buckel, R, said the lack of connectivity is “clearly disadvantaging” his more isolated constituents. The government, he said, should facilitate internet access for all Marylanders as they do roads, water and sewer service.

“We need the government to make it possible, and subsidize it to an extent so that the private sector provider could get that high speed internet real real close to our house,” he said.

Delegate Brooke Lierman, D-Baltimore, wrote in an email: “State and private actors have been trying different strategies over the years to push connectivity forward, but none of it has been fast enough or comprehensive enough.”

In the next Maryland General Assembly, Lierman said she plans to introduce legislation with Sen. Sarah Elfreth, D-Annapolis, to “broaden the reach and mandate” of the Office of Rural Broadband to address disparities in all 24 jurisdictions, “not only so that every resident in Maryland can be connected to the internet, but also that every resident in Maryland knows how to use the internet.”

Sen. Katie Fry Hester, D-Carroll and Howard, who co-chairs the Joint Committee on Cybersecurity, Information Technology and Biotechnology, said she will introduce legislation to address the per pupil and school staff member digital costs.

Expanding the Office of Rural Broadband, Hester said, is important because “needs change, and the amount of work has changed, and it’s not just rural broadband.”

Policy advocates expect to throw their support behind broadband expansion efforts in January’s General Assembly.

“It’s all about the big picture, obviously, of how we can move the ball forward,” said Drew Jabin, a policy associate with the Maryland Association of Counties.

In the meantime, Vasquez has taken matters into her own hands by becoming a connectivity activist. In partnership with Coy’s Digital Harbor Foundation, she produces a podcast on Baltimore’s internet disparities.

And her student-led advocacy group, Students Organizing a Multicultural and Open Society, or SOMOS, in May sent a letter to Comcast with a list of demands, including faster speeds and free access for low-income families.

In its response, Comcast “welcomed a partnership” with SOMOS to “raise awareness of the Internet Essentials program” to get more Baltimoreans connected to the internet, and detailed assistance they had already established during the pandemic, like canceling late fees and providing two months of free service for new customers.

Vasquez says the mental exhaustion of getting repeatedly “kicked out” of her virtual classroom sometimes makes her want to give up trying to connect.

“It’s hard to remind myself that it’s not because of me,” she said. “It’s just, I’m not provided with the tools that I need.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.