The Biden administration’s attempts to revive talks with Iran over curbing its nuclear program are complicated by continuing tensions over human rights abuses, the unsolved fate of the longest-held American hostage, Iranian proxy attacks on U.S. troops in Iraq, and bipartisan pressure from Congress to expand the parameters of any new deal.

The State Department announced on Feb. 18 the United States would accept an invitation from the European Union High Representative to attend a meeting of the five United Nations Security Council members and Iran to discuss the future of the Iranian nuclear program.

The Biden administration has since rescinded former President Donald Trump’s determination that all U.S. sanctions against Iran must be restored; also rescinded were heavy travel restrictions on Iranian diplomats posted to the United Nations.

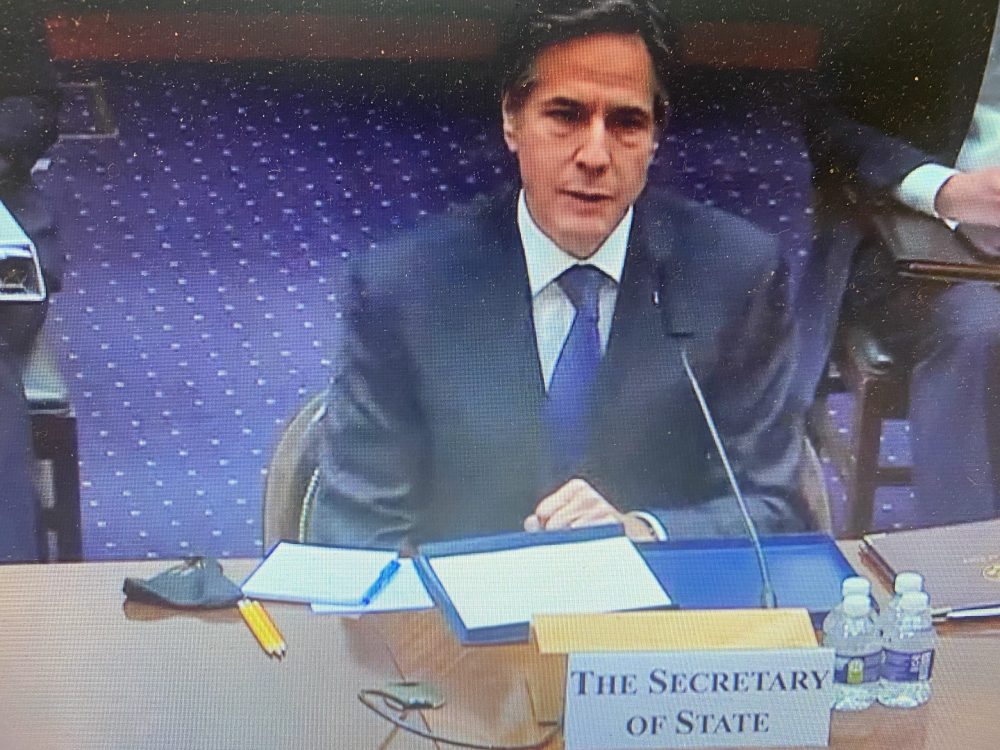

Despite these steps, the administration has made it clear the United States would only return to the 2015 nuclear agreement if Iran would comply with the original terms. Secretary of State Antony Blinken reassured lawmakers Wednesday at a House Foreign Affairs Committee hearing that those requirements have not changed.

Iran announced on Feb. 23 that it had halted voluntary implementation of additional protocols agreed to under the deal, a sign interpreted by the international community that Tehran intended to ramp up its nuclear program.

Iran also initially indicated it was not willing to attend EU-brokered talks with Washington regarding the deal. Iran’s leaders cited as a prime reason for the continuing heavy sanctions imposed by Washington.

“Considering the recent actions and statements by the United States and three European powers, Iran does not consider this the time to hold an informal meeting with these countries, which was proposed by the EU foreign policy chief,” Iran Foreign Ministry spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh said Feb. 28.

Iran has since softened, announcing last Friday that it would be ready to resume talks if the United States and other western powers provide a “clear signal” that sanctions, dating back to the Carter administration, will be lifted within a year.

In a meeting with Irish Defense Minister Simon Coveney, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani said, “Iran is ready to immediately take compensatory measures based on the nuclear deal and fulfill its commitments just after the U.S. illegal sanctions are lifted and it abandons its policy of threats and pressure.”

In an interview with the Financial Times, former Revolutionary Guards commander and potential conservative presidential candidate Mohsen Rezaei said sanctions would have to be lifted monthly, with top priority given to financial transactions and oil exports.

Even so, the fraught U.S.-Iran relationship has multiple unresolved issues.

On Tuesday, the State Department urged the Iranian government to address the disappearance 14 years ago of former FBI agent Robert Levinson. U.S. officials believe he was taken hostage off Iran’s coast, but Tehran has denied it knows anything about him. Levinson’s family has said it is likely he died in Iranian custody.

“We call on the Iranian government to provide credible answers to what happened to Bob Levinson and to immediately and safely release all U.S. citizens who are unjustly held captive in Iran,” Blinken said in a statement. “The abhorrent act of unjust detentions for political gain must cease immediately.”

Also on Tuesday, the State Department designated two interrogators with the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps “for their involvement in gross violations of human rights, namely the torture and/or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment of political prisoners and persons detained during protests in 2019 and 2020 in Iran,” Blinken said.

Under the designation, the two will be barred from entry to the United States.

“We will continue to consider all appropriate tools to impose costs on those responsible for human rights violations and abuses in Iran,” Blinken said. “We will also work with our allies to promote accountability for such violations and abuses.”

Iran and the United States also are colliding in the Mideast, where Iran-backed militia in Syria last month attacked American troops in Iraq. President Joe Biden subsequently ordered retaliatory airstrikes.

Such clashes underscore concerns among Democrats and Republicans in Congress that renewing the nuclear deal must encompass broader issues such as Iran’s efforts to expand its influence in the region and its sponsorship of terrorism.

In a letter Tuesday organized by Reps. Anthony Brown, D-Largo, and Michael Waltz, R-Florida, a bipartisan group of 140 House members told Blinken that the United States and its allies “must engage Iran through a combination of diplomatic and sanction mechanisms to achieve full compliance of international obligations and a demonstrated commitment by Iran to addressing its malign behavior.”

“Three core tenets – their nuclear program, their ballistic missile program, and their funding of terrorism – must be addressed from the outset,” the lawmakers wrote.

The nuclear deal, formally known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), has been in limbo following the U.S. withdrawal in 2018 by Trump.

Negotiated during the Obama administration and in partnership with the five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, the agreement was created to limit Iran’s nuclear program and uranium enrichment.

In response to Washington’s withdrawal, Iran began ramping up nuclear activity, enriching uranium up to 20%, above the 3.67% limit set in the 2015 deal, but under the 90% level of weapons-grade uranium.

Under the terms of the nuclear deal, Iran is only allowed to enrich uranium with a certain type of less sophisticated centrifuges. Since the United State’s withdrawal from the agreement, Iran has installed advanced centrifuges.

A report issued Monday by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) found that Iran began enriching uranium with a third centrifuge cascade, directly violating the clause regarding centrifuge technology.

Tensions between Washington and Tehran have been mounting since the withdrawal, escalating in 2020 with the death of the commander of Iranian forces, Qassim Suleimani, in an airstrike in Iraq.

Iran will prove as intransigent under the Biden administration as it was during the Trump years, according to Ellie Geranmayeh, senior policy fellow and deputy director of the Middle East and North Africa program at the European Council on Foreign Relations. She spoke at a Brookings Institution panel on Iran last month.

Geranmayeh believes that despite Iran’s economic state, the government believes it can manage and even prolong an impasse for another four years if need be, while also expanding nuclear activities to the levels negotiated in the initial 2015 agreement.

She added the Iranian government’s position on the country’s economic status can be backed up from data coming from the International Monetary Fund and World Bank that “suggest that Iran, even with Trump-era sanctions in place, even with the COVID pandemic, is likely to see a marginal upward growth.”

She said that, based on the data suggesting that sanctions are not hurting Iran that much economically, she doesn’t “see any appetite in Tehran right now to negotiate the JCPOA minus or JCPOA plus.”

However, she said that Iran has left the door open to diplomacy “without moving the goalposts,” making it possible for its return to the negotiating table.

But Alex Vatanka, the director of the Iran Program at the Middle East Institute, believes Tehran has no choice but to come back to the table given its current economic troubles.

“They don’t have much choice about what they like and what they don’t like,” Vatanka told Capital News Service. “The question is, how much more sanctions can they endure? They are economically not in a good place.”

He said Tehran’s hope is to reach a settlement, whether directly or through mediations by the Europeans. But in order to get there, Tehran has to go back and restrict its nuclear activities to convince Washington to lift the sanctions.

Vatanka said if the talks preliminary to negotiating are successful, then “you can envision a situation where Iran and the U.S. can talk about other issues of concern, including Iran’s regional agenda, its ballistic missile arsenal, and more.”

When it comes to the issue of sanctions, which date back to President Jimmy Carter and the dissolution of the Iranian monarchy, Vatanka said the easier solution for the U.S. will be to “lift principle sanctions on (Tehran), including Iran’s ability to sell oil related to be able to access international banking system that those two things are the most important part of the sanctions that they like.”