WASHINGTON – A year and a half into the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers and health organizations are still trying to determine the extent of its impact on Americans’ mental health, but early data suggests it is significant.

Self-reported symptoms of anxiety and depression among American adults have more than tripled during the pandemic, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics has been gathering data on mental health changes during the pandemic with Household Pulse Surveys. Data released for early September shows 28.1% of American adults self-reporting symptoms of anxiety and 22.4% reporting symptoms of depression.

This time two years ago - roughly six months before the pandemic took hold - 7.4% of American adults reported anxiety symptoms and 6.4% reported depression symptoms, according to a National Health Interview Survey, also conducted by the NHCS.

Early in the pandemic, many mental health professionals expressed fears that the added stressors would lead to an increase in the suicide rate across the nation. Provisional data from the CDC shows national suicide deaths actually decreased by 5.6% from 2019 to 2020. While the decrease in completed suicides holds true for the state of Maryland, emergency department visits for suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts have increased during the pandemic.

September is National Suicide Prevention Month.

“We know that suicide risk has increased, even if suicide death has not shown increases on the general population,” Dr. Jodi Frey, professor at the University of Maryland’s School of Social Work, told Capital News Service. “So what that tells me as a researcher, and previously as a practitioner, is I don't need to wait for data to show me that deaths are increasing. If I know risks are increasing, we need to act now.”

In Maryland, 9,837 individuals went to emergency departments for suicide attempts and thoughts of suicide in the first half of this year, compared to 9,200 individuals during the same period in 2019, according to the state Department of Health.

The number of people using the state’s public behavioral health system (which includes services like therapy) is down for 2021 compared to the 2019 figures so far, according to Dr. Aliya Jones, Maryland Department of Health’s Deputy Secretary of Behavioral Health Administration.

“And that can certainly translate into people having more behavioral health crises” that require emergency care, Jones said. “People are clearly in distress, and are utilizing crisis services more than they have before.”

Amid increases in emergency care for suicide attempts and suicidal thoughts, state health officials also have noted a decrease in patients at psychiatric hospitals during the pandemic.

“I think that the decreases on the inpatient side may just represent that people are possibly staying in the hospital longer than they were before because it's harder to move people back into the community, particularly if you're moving them into residential environments because of the concerns about COVID,” Jones said. “COVID status makes it difficult.”

She also noted a possible decrease in available inpatient psychiatric beds, as some may have been commandeered to serve COVID patients during the pandemic.

According to Frey, assessment and response to suicide risk has also been improving over the last few years. She said hospitals have been using screening tools and other assessments to provide the least-restrictive plans for people struggling with suicidal thoughts.

“Going to the emergency room is usually not helpful to someone who has suicide ideation. And in fact, research shows us that it can be harmful,” Frey said. “So we really think about, as suicideologists, the emergency department and inpatient care, as a last resort, and try to think about what coping and supports a person has in their family and community so that they can receive care without necessarily going inpatient.”

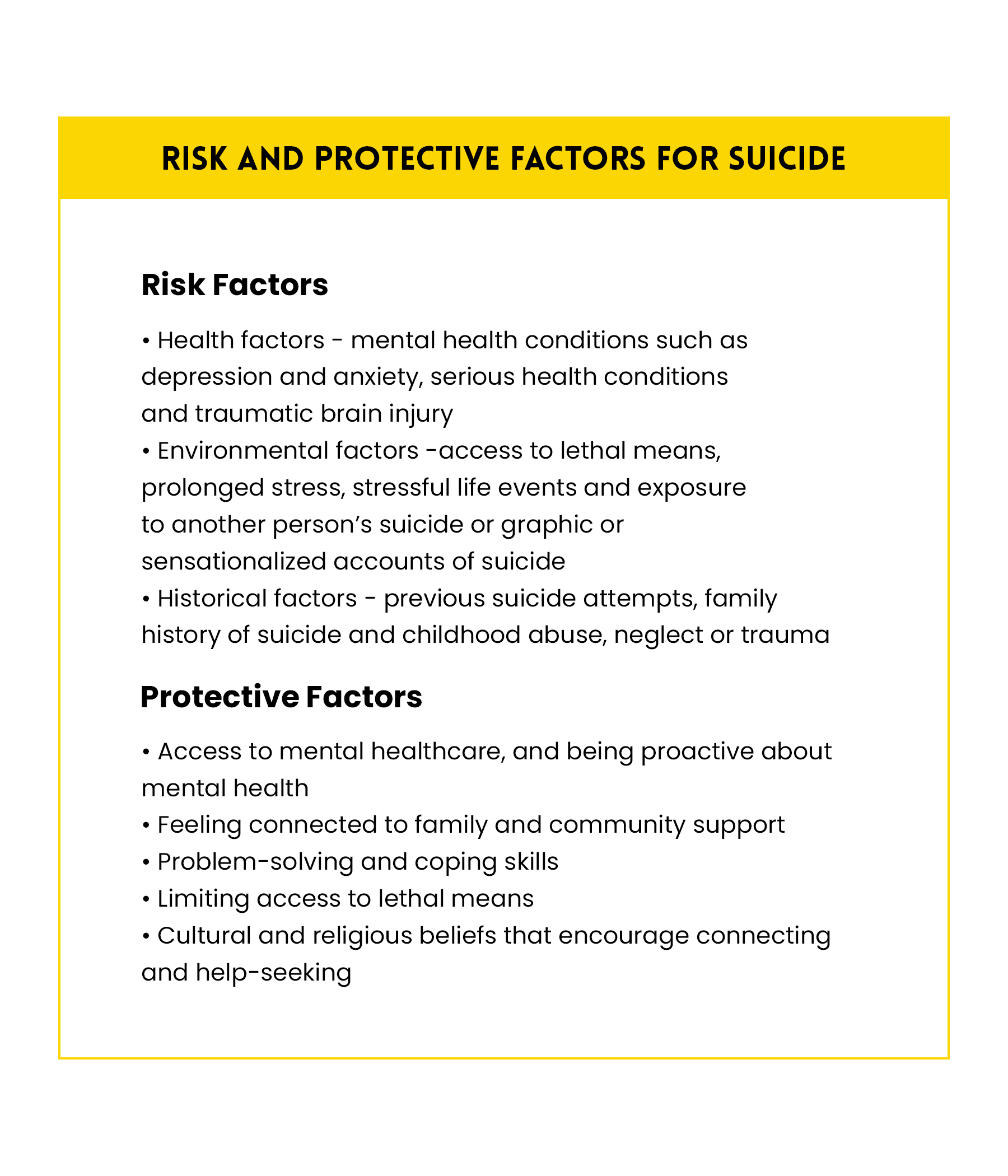

While the impact of the pandemic on overall mental health and suicide risk is being documented, suicide has no sole cause.

“Suicide happens when multiple stressors, multiple health issues and other risk factors converge,” said Meredith Glaze, loss and healing chair of the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention National Capital Area Chapter. “And that's what creates that sense of hopelessness, a sense of despair, that may eventually lead to someone to die by suicide.”

The Maryland Department of Health has noted that the largest numbers of people seeking emergency care for suicidal thoughts and attempts during the pandemic were those under 17 and people between the ages of 35 and 54.

Jones attributed the younger group seeking emergency care at least partially to the impact of not being in school, where students can often receive behavioral health resources and social support. She added that kids re-entering schools may help bring those numbers back down to more traditional metrics.

Other demographic populations have experienced disproportionate increases in suicide risk during the pandemic as well.

“When you talk about suicide and suicide prevention, I think it's important for us to recognize that we were already functioning in a very stressed, and what I would probably consider a broken, mental health system,” Frey said. “Meaning that a lot of people, particularly those in more vulnerable groups, that are at higher risk now for suicide due to COVID implications.”

Frey specifically noted that exceptional stress is affecting essential workers, those experiencing job loss or unstable employment or housing, and people of color.

“Particularly in Maryland, we've seen research over the past year and a half showing that suicide rates for Black Americans have increased, where some of the rates throughout the country have actually decreased for suicide death,” Frey said.

Suicide ranks 11th among leading causes of death in the United States, with COVID-19 currently 3rd after joining the list last year, according to The Journal of the American Medical Association.

Glaze said there are ways to spot and help those in crisis: be mindful of other people, pay attention to warning signs such as someone talking about suicide or showing big changes in behavior, have honest conversations about any concerns and provide resources such as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline.

Looking ahead, Frey says she’d like to see an investment of funds in training for mental health professionals, as well as support to allow graduates the opportunity to do triage and therapy as they work on getting licensed.

“It was critical before COVID, and now it's a crisis,” Frey said.

Long-term, Frey said, it’s also necessary to re-assess the overall mental healthcare system and insurance policies related to mental health. She said finding ways to expand the workforce and make sure providers are paid and encouraged to stay in the system could help more vulnerable populations receive care.

“Mental health care should be a right, not a privilege,” Frey said. “And right now, I think for a lot of people, it's a privilege that's not affordable.”

If you are struggling with thoughts of suicide, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1(800)273-8255 or visit its website at https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/. The Lifeline offers 24/7, free and confidential support.

You must be logged in to post a comment.