WASHINGTON — Two decades after the terrorist attacks, the White House’s new executive order to declassify confidential documents regarding Sept. 11, 2001, underscores the government’s propensity to keep secrets long after they are useful, according to some intelligence experts.

“It is frustrating because it shouldn’t have been necessary to issue this order,” Steven Aftergood, director of the Project on Government Secrecy at the Federation of American Scientists, told Capital News Service.

Twelve years ago, then-President Barack Obama issued Executive Order 13526, requiring that “information shall be declassified as soon as it no longer meets the standards for classification under this order.”

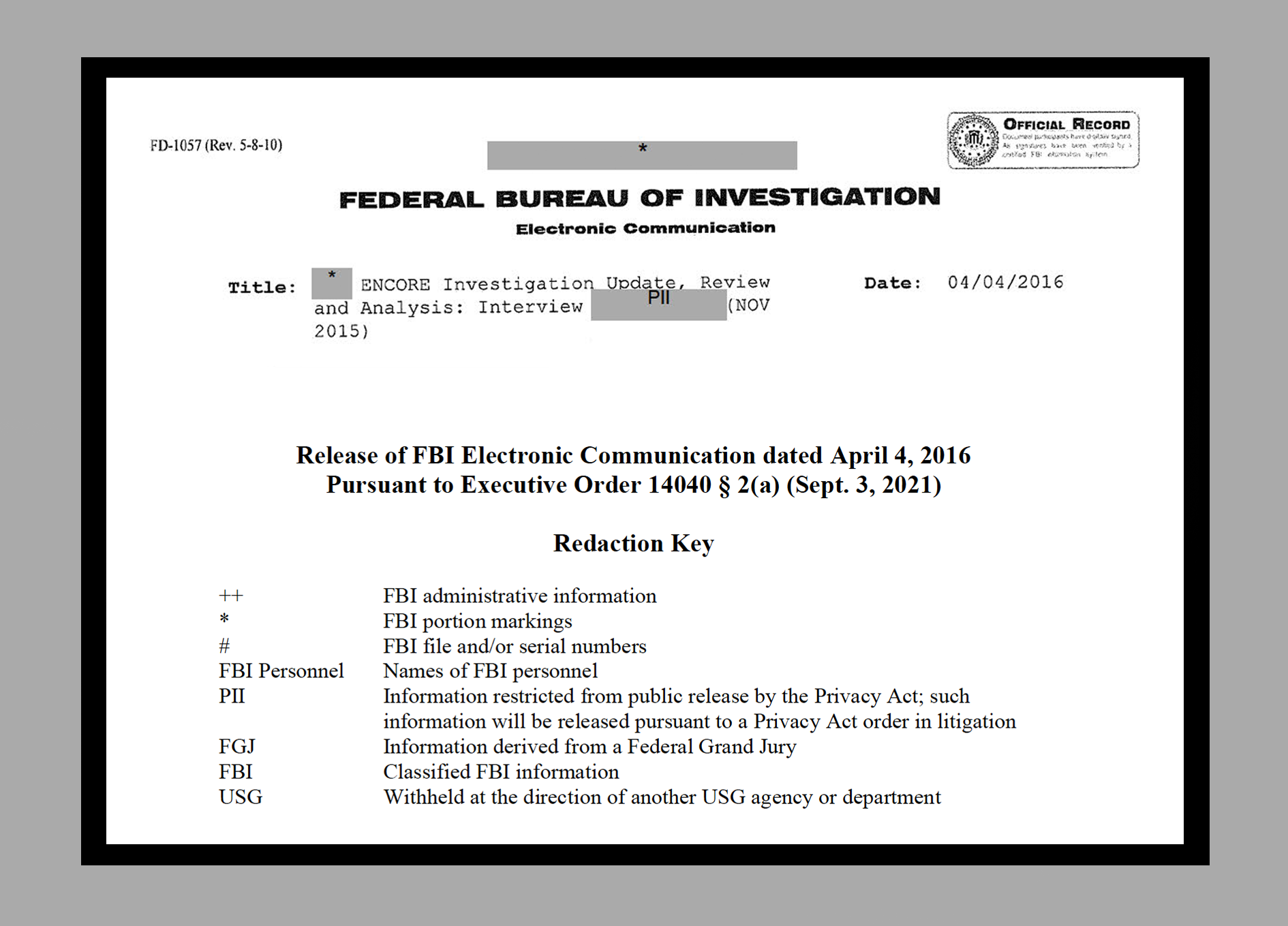

On Sept. 3, President Joe Biden signed an executive order directing federal agencies under the jurisdiction of the executive branch to exclusively review Sept. 11 records that can be declassified within six months.

Biden said he “made a commitment to ensuring transparency” in the wake of the terror attacks, one he’s now honoring, according to a statement. But Aftergood says otherwise, suggesting the new executive order is too limited in scope, compared to the Obama-era mandate.

“If this order was going to be issued, then it should have been bolder in its requirements,” he added.

Congress has been grappling with the overclassification of documents for decades and the pandemic made that problem significantly worse. Mark Bradley, director of the Information Security Oversight Office in the National Archives and Records Administration issued a stern warning in its 2020 annual report to the president.

“The pandemic adversely affected every aspect of our Classified National Security Information and Controlled Unclassified Information systems,” Bradley wrote. “It shuttered buildings, limited or prevented access to classified networks, forced many federal workers to telework or work remotely, delayed the modernization and deployment of badly needed technological updates, crippled oversight efforts, and dramatically slowed the declassification of historically important records, increasing an ever-expanding backlog.”

David Priess, a former CIA intelligence officer during the administrations of Bill Clinton and George W. Bush, said national intelligence agencies are “perennially underfunded and under-resourced,” which delays their ability to process and produce classified records for public release.

“The whole point of these documents on 9/11 coming out is, if we’re going to do it, we need to do it without redactions, because that’s kind of the point,” Priess added.

Jeremy Bash, a former CIA chief of staff and Defense Department in the Obama administration, told CNS there “are always delicate balances to strike” in declassifying aging documents.

“But I think we should err as much as possible on the side of transparency,” Bash said. “I’m confident that if the president, after consulting with the relevant agencies, determines that we can protect sources and methods, I’m confident that declassifying information about 9/11 is in the public interest and will not compromise national security.”

Even though the 9/11 Commission Report — published with many redacted pages in 2004 — was created at the direction of Congress, it’s now technically in the possession of NARA, an independent executive branch agency whose origins date back to 1934.

“A large percentage” of an estimated 570 cubic feet of the commission’s supporting records remain classified for national security reasons, even though some were opened in January 2009, according to the agency.

In an explanation to Capital News Service, the National Archives said it is exempt from Biden’s executive order. Only documents used in court cases and records from PENTTBOM, the codename for the FBI’s probe on 9/11, are being reviewed for declassification, according to the Archives’ interpretation of the new order.

Yet anyone may still be able to file mandatory declassification review requests for 9/11 Commission records through the Center for Legislative Archives, even though the agency lacks legal authority to actually release them.

Last November, the Interagency Security Classification Appeals Panel, a presidential appellate panel composed of representatives from federal intelligence agencies that oversees appeals for mandatory declassification, released 26 documents created by the 9/11 Commission.

Sens. Chris Murphy, D-Connecticut, and Ron Wyden, D-Oregon, are seeking to depoliticize classified information by creating congressional accountability and oversight of ISCAP through the reintroduction of the Transparency in Classification Act, a bill that had languished in the previous Congress.

Murphy, who sits on the Senate’s Foreign Relations Committee’s Near East, South Asia, Central Asia, and Counterterrorism subcommittee, believes “overclassification for political purposes undermines Congress’s ability to hold the executive branch accountable and unnecessarily keeps the American public in the dark.”

“Regardless of the administration, protecting the integrity of the classification system is a matter of national security—not politics,” Murphy said in a statement. “We’ve seen the serious harm that politicization of intelligence can cause, and our legislation restores congressional oversight and supports President Biden as he works to unravel the damage done by his predecessor.”

Although the FBI already released a 16-page memo from August 2016 on Sept. 11 — the first of its kind since the new executive order was enacted — Aftergood said he wanted to “see something more ambitious.”

He would like to see “drop dead” dates established for sensitive documents: classified designations on any records exceeding 40 years in age would expire and be subject to immediate declassification.

Aftergood said the Biden executive order should have explicitly stated that all 9/11 documents are to be declassified — except in cases where methods or sources are susceptible to being compromised.

Implementing a definitive “drop dead” date would “free up a lot of bureaucratic resources,” Aftergood insisted, allowing agencies to review more complicated documents instead.

Incredibly, federal agencies still conduct most declassification reviews by hand, according to the Public Interest Declassification Board, created by Congress to advise the executive branch on policies regarding the handling of national security information.

The board issued a report last year recommending ways the nation’s classification and declassification of documents can be conducted more efficiently.

“Transformation will be difficult,” board Chair Trevor W. Morrison and Acting Chair James E. Baker wrote in their transmittal letter to then-President Donald Trump. “When it comes to declassification, the government is still in the analog age.”

“The current system was created before the United States entered World War II, and it remains entrenched today,” Morrison and Baker said. “Despite rapid increases in the volume and variety of digital data, the government still relies upon inefficient and ineffective paper-based processes.”

The federal government is woefully ill-prepared for classifying and declassifying digital information, the board warned.

The Information Security Oversight Office estimated that the government spent $18.4 billion on its security programs in fiscal 2017. Just $102 million of that was spent on declassification of information.

Priess believes all of the power still lies with the president to make the final call on what becomes public and what stays secret.

He asked: “Is there a president who is willing to say, ‘You know what, the historical value of these documents and the need to be open and transparent overrides any remaining national security concerns?’”

“9/11 is the core issue here but declassification is a problem that extends across the executive branch,” Aftergood said. “It needs some focused attention, if we’re going to ever get it right.”

[Like what you’re reading? Subscribe to our newsletter for more!]