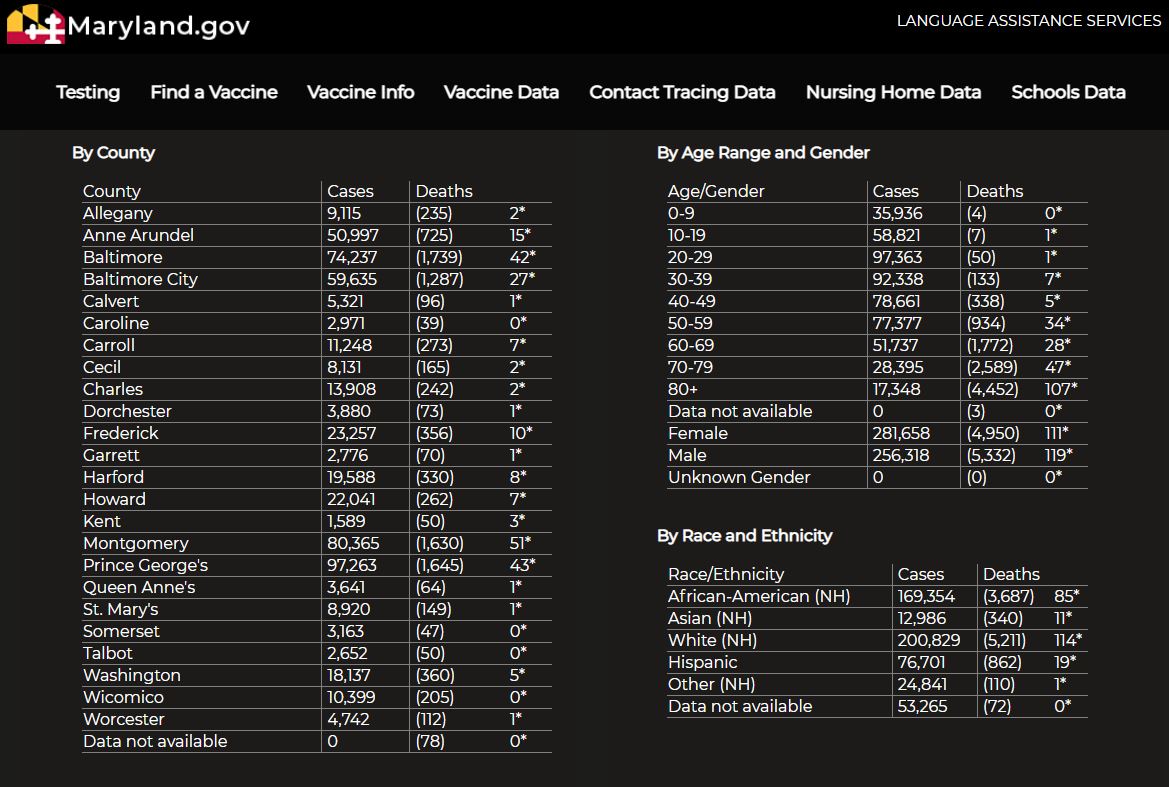

ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Lumped into the “Other” racial and ethnic category, American Indians and Alaska Natives are effectively invisible on Maryland’s state website for COVID-19.

More than 120,000 people who identify as Native American live in Maryland, but without public-facing numbers of COVID-19 cases and deaths, it is a mystery how many the disease has affected — and how many resources should be allocated to help them.

“Not only is that bad public health, but it’s also very dehumanizing for American Indians and Alaska Natives on our native lands,” Kerry Hawk Lessard, executive director of the health services nonprofit Native American Lifelines of Baltimore, said to Capital News Service.

The Maryland Department of Health puts American Indians and Alaska Natives in the “Other” category for COVID-19 cases and death numbers “due to low statistical occurrence given the population of Native Americans in the state,” department spokesperson Andy Owen wrote in an email to Capital News Service.

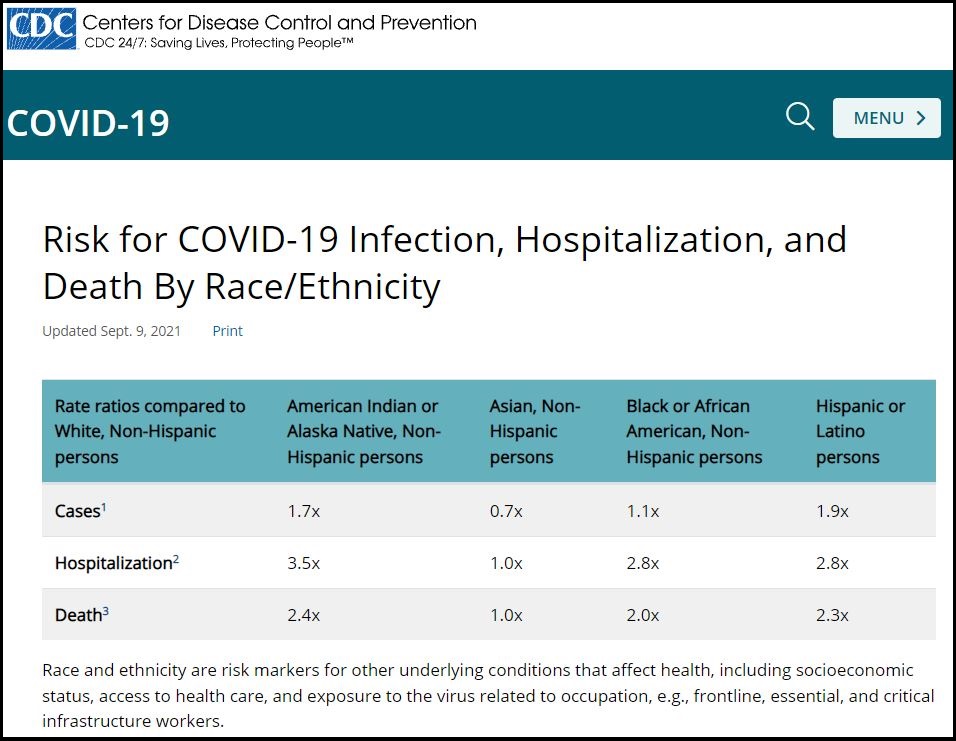

However, American Indians and Alaska Natives are at the highest risk for death and hospitalization from COVID-19 among all races and ethnicities, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“There is no regulation that requires this manner of reporting,” Owen wrote, when asked if any regulation requires Maryland to put American Indians and Alaska Natives in the “Other” racial and ethnic category.

Race and ethnicity are self-reported data points, Owen added.

However, the Maryland Department of Health does not publish the number of self-identified Native Americans or Alaska Natives who contracted COVID-19 or died from the disease.

Owen did not specify which other races and ethnicities are included in the “Other” category of the state’s COVID-19 dashboard.

In Maryland, 31,845 people identify as American Indian and Alaska Native alone, comprising 0.5% of the state’s total population, according to the 2020 U.S. Census.

“So our lives don’t matter because there aren’t enough of us?” Hawk Lessard, who identifies as a descendant of Shawnee, Assiniboine, and European people, said to Capital News Service.

An additional 96,805 people in Maryland identify as American Indian and Alaska Native in combination with one or more races, according to a Capital News Service analysis of data from the 2020 census. This group comprises an additional 1.6% of the state’s total population.

Nationally, American Indian or Alaska Native people are more likely to die from COVID-19 than any other race or ethnicity, according to a September CDC report.

Compared to their non-Hispanic white counterparts of a similar age, American Indian or Alaska Native people are 1.7 times more likely to be infected with COVID-19, 3.5 times more likely to be hospitalized, and 2.4 times more likely to die from the disease, the CDC found.

In Maryland, “there is an invisibility to Native people that is amplified by the state’s refusal” to publish COVID-19 case and death numbers for American Indians and Alaska Natives, said Hawk Lessard, who also serves as a governor-appointed member of the Maryland Commission on Indian Affairs.

“It means that we don’t know what the health status of Native people is,” Hawk Lessard said, which negatively impacts COVID-19 outreach, testing and vaccination efforts.

Not all Maryland jurisdictions follow the state’s example.

Baltimore City, for instance, includes “American Indian or Alaska Native” and “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander” as options in its COVID-19 dashboard, though the Maryland Department of Health does not.

Jennifer Hunt, a civil servant for the federal government and a former board member of Native American Lifelines, helped convince the Baltimore City Health Department last year to begin publishing Native people’s COVID-19 data.

“We noticed that our race was not on the city dashboard,” said Hunt, who identifies as a descendant of the Choctaw tribe.

In July 2020, Hunt co-wrote a letter with Baltimore City Councilman Zeke Cohen requesting the city’s health commissioner to add American Indians and Alaska Natives to all data collection efforts.

“Within 48 hours, we were up and running on the Baltimore City COVID dashboard,” Hunt said.

The story is markedly different in Montgomery and Prince George’s counties, where some of the largest Native populations in Maryland live, according to data from the 2020 census.

Neither county’s COVID-19 dashboard lists “American Indian or Alaska Native” as a category. Like the state of Maryland, Montgomery County also puts Native people in the “Other” category.

“Collapsing racial-ethnic groups with small cell counts is standard practice when reporting health data to avoid unintentionally identifying anyone,” Mary Anderson, a spokesperson for Montgomery County Health and Human Services, wrote in an email to Capital News Service.

To comply with federal health privacy laws, the Montgomery County health department avoids publishing COVID-19 case and death numbers that are smaller than 25, Anderson explained.

As of Sept. 15, there were 170 cases of COVID-19 among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Montgomery County, Anderson added.

Though the case number was higher than 25, the county did not publish it.

“The counts of cases among Native Americans were too small to allow for reporting when stratifying by other variables (age, sex, month, etc),” Anderson wrote.

Adrian Dominguez, chief data officer at the Urban Indian Health Institute, told Capital News Service that he disagrees with the county’s decision to not publish the data.

According to Dominguez, the department can publish the aggregate number -- 170 COVID-19 cases among American Indians and Alaska Natives in Montgomery County -- without publishing the smaller numbers corresponding to those individuals’ age, sex and month of infection.

“Either they don’t know what they’re doing, or they’re intentionally not wanting to show this information,” Dominguez said.

In addition to Maryland, 13 other states do not clearly publish data about American Indians and Alaska Natives in their COVID-19 dashboards, according to a February report by the Urban Indian Health Institute.

The states are Alabama, Delaware, Florida, Hawaii, Indiana, Kentucky, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia.

“In a world where data is dollars, erasing people from data is essentially erasing them from the system,” Meredith Raimondi, director of congressional relations and public policy at the National Council of Urban Indian Health, said to Capital News Service.

“If we don’t have adequate data to show this need is there, then the money won’t come and the resources won’t come...I’ve seen in the past year and a half how much it literally impacts lives,” Raimondi said.

[Like what you're reading? Subscribe to our newsletter for more!]

*Story corrected from its original version. Updates name of National Council of Urban Indian Health.

You must be logged in to post a comment.