STORY HAS BEEN CORRECTED.

An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated that 80% of Nonprofit Prince George’s County member organizations operate on $25,000 or less. Actually, 80% of all nonprofits registered in Prince George’s County operate on $25,000 or less. Nonprofit Prince George’s County reported that 50% of its 150 members operate on $250,000 or less, which is the lowest tier of financial information recorded. The sixth and seventh paragraphs have been updated. The earlier version also misquoted Tiffany Turner-Allen in the 24th paragraph. She said “pressure bursts pipes,” not “pressure must pipe.”

ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Tiffany Turner-Allen said she is tired of her nonprofit organization and workers being seen as resilient and coworkers calling themselves martyrs to their community causes.

“We’re expected to do good and do well from a place of scarcity,” said Turner-Allen, who runs Nonprofit Prince George’s County, a group supporting other nonprofits on a $300,000 budget.

Minority-led nonprofits struggled disproportionately during the pandemic, fueled by hard-to-reach government funding and catastrophic losses on every income source, according to Maryland Nonprofit survey data released Dec. 1.

To counter this distress, over 215 nonprofits and individuals are calling for state administrators to allocate $1 billion of Maryland’s reported budget surplus to aid struggling nonprofits, with half of that spent in the near term, and half set aside in years to come.

When the pandemic hit, Turner-Allen, who is Black, said she worked 16-hour days or longer seven days a week with a 1-year-old at home. Her organization didn’t have the money or staff to ease the pressure, she said.

On average, 80% of over 4,000 registered Prince George’s County nonprofits operate on $25,000 or less, Turner-Allen said to Capital News Service in a phone interview.

Of Turner-Allen’s organization’s 150 member nonprofits, 50% operate on $250,000 or less, the lowest tier of financial information the organization collects. Smaller organizations may not have the resources to participate in Nonprofit Prince George’s County meetings, she said Wednesday.

When a full-time employee can cost $30,000 to $40,000, these smaller organizations rely on volunteer work, but volunteers are burnt out, she said.

“Prince George’s County has experienced the brunt of the pandemic,” Turner-Allen said, calling the county a “majority-melanated community” that felt great job loss and death tolls.

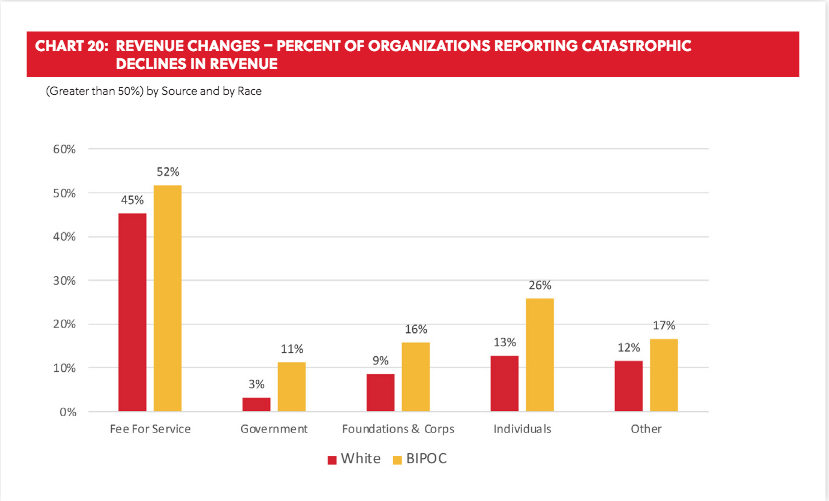

Minority-led nonprofits made up 60% of those with revenues under $25,000, and were more likely to have experienced declines over 50% in all revenue sources, according to Maryland Nonprofits’s COVID-19 Pandemic and Racial Equity Survey.

The survey received 710 unique responses from nonprofits across the state about finances from August 2020.

The Paycheck Protection Program, which reached 60% of responders, was the government funding opportunity most used by surveyed nonprofits. It was less accessible, however, to those led by people of color, the survey reported.

“They were less likely to be eligible, less likely to hear about it and more likely to be declined than white-led organizations,” according to the report.

Turner-Allen tried to ameliorate the struggles of fellow nonprofits, and started work in June on a resource center for nonprofits in Vista Gardens Marketplace, a shopping mall in Bowie.

After months of work painting, organizing furniture donations and calling in favors for wiring while her young son napped on a corner cot, Turner-Allen said the center has rented out three of its four office spaces to nonprofit organizations needing administrative spaces — but it won’t break even until all four are filled.

The center also offers mailboxes for rent, giving nonprofits an opportunity to apply for some grants requiring a physical address.

Funding has been inaccessible in more ways than that, Turner-Allen explained.

Some applications require the same long application no matter how much money is applied for, increasing the administrative burden on smaller nonprofits, she said — those without the resources to complete an application are sometimes unable to apply for more resources.

Others, like that for an operating assistance grant through the Maryland Department of Housing and Community Development, first announced aid would be distributed in August, but she said as of Dec. 7, nearly halfway through the fiscal year, money still hadn’t been doled out.

Carol Gilbert, assistant secretary for Neighborhood Revitalization in the state housing department whose office manages the grant, said in a phone call Tuesday that the awards are in the final stages of review and likely will be announced by the end of the calendar year.

“I’m not saying they’re not overwhelmed,” Turner-Allen said of grant-managing agencies. “I am saying that if a nonprofit operated in the same way the government is allowed to, we would be shut down.”

There’s an expectation that nonprofits can simply shoulder financial burdens, she said, continuing to do more with less in a crisis, the full mental strain of which is yet unknown.

Turner-Allen compared resilience versus value to the care of a rugged pick-up truck versus an antique car. The truck is driven through mud and rocky roads, taking dings and scrapes because it’s perceived it can. The antique car, however, is protected, kept under cover and wiped down.

“Pressure bursts pipes. Get out of the narrative that we’re resilient, and start valuing Black and brown leadership.”

Turner-Allen spoke at a “Putting People First” press conference Dec. 1 announcing a letter to state administrators requesting that $1 billion of surplus funds be reallocated to aiding nonprofits.

“The stress and strain is unbearable, and it is untenable,” she said at the conference, hosted by Maryland Nonprofits.

Over 215 organizations and individuals have signed the letter, which has been submitted to Gov. Larry Hogan, Comptroller Peter Franchot, outgoing Treasurer Nancy Kopp, and Senate President Bill Ferguson, among others.

The letter lists four improvements for grant allocation processes: adequate staffing for public grant and contracting agencies; delegating administration to nonprofit intermediaries; simplified applications and reports; and timely payments.

The letter also lists overall priorities moving forward, including emphasizing basic human need services, like bilingual behavioral health services and food and rental assistance, as well as increasing pay to essential human service workers, who are likely to be women, minorities and sole breadwinners.

The letter also requests emphasis on funding vocational schools and apprenticeships to help skilled workers enter the workforce to support a post-pandemic economy.

You must be logged in to post a comment.