ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Aggregated race data – which lumps Asians into one category despite their different countries of origin – is masking health and educational disparities in Asian American communities, people across Maryland and the country told Capital News Service.

Nationally, Asian Americans are the fastest-growing racial group, increasing 36% from 2010 to 2020, according to a Brookings Institution analysis of census data in September.

They come from many different cultural and ethnic backgrounds across Asia, but aggregated data may represent some groups more than others, said Neil Ruiz, associate director of race and ethnicity research at the Pew Research Center, in an email to Capital News Service.

For example, Chinese, Indian and Filipino Americans are more represented in aggregated data than Pakistani or Laotian Americans, because the former groups make up a much larger share of the country’s Asian population than the latter, Ruiz said.

The larger groups tend to have higher income levels and more formal education than the smaller Asian origin groups, Ruiz explained.

Effectively, experiences from the smaller groups may get buried.

“Without disaggregated data, communities will remain invisible and ignored in legislation and in the allocation of resources,” said Lan Đoàn, a postdoctoral researcher at New York University’s Center for the Study of Asian American Health.

Possible resources going unallocated include vaccination outreach, COVID-19 testing, food stamp benefits and language translation services, Đoàn said.

“That’s why it’s important to have better data,” Đoàn said, “So we can say – look, X percent of the population is in high need, and they require funding and resources.”

ASIAN DISPARITIES

The nation’s disaggregated datasets are few and far between, costing considerable money and time to create and implement, Đoàn said.

However, the U.S. Census collects and shares disaggregated data that helps pinpoint some disparities.

In terms of education, about 33% of all Americans ages 25 and older had a bachelor’s degree or more in 2019 — but only 18% of Laotians and 15% of Bhutanese had the equivalent, compared to 75% of Indians and 65% of Malaysians in the U.S., according to a Pew Research Center report in April that analyzed census data.

Mongolian and Burmese Americans had the highest poverty rates among all Asian origin groups, at 25% – more than twice the national average and about four times the poverty rates among Indians, according to the same report.

“There’s a myth — kind of along the ‘model minority’ myth — that most Asian Americans are well off and have stable jobs and therefore don’t have to worry about healthcare,” said state Sen. Clarence Lam, D-Howard and Baltimore Counties, who serves as vice chair of the Maryland Legislative Asian-American & Pacific-Islander Caucus.

“But we have members of the community – who are maybe newer immigrants, maybe working more than one job and don’t have health insurance – that need our support to get adequate healthcare,” said Lam, who is also a physician and program director at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

“Without that data, it’s hard to do targeted outreach. Data disaggregation is important in that way,” Lam said.

COVID-19 STAKES

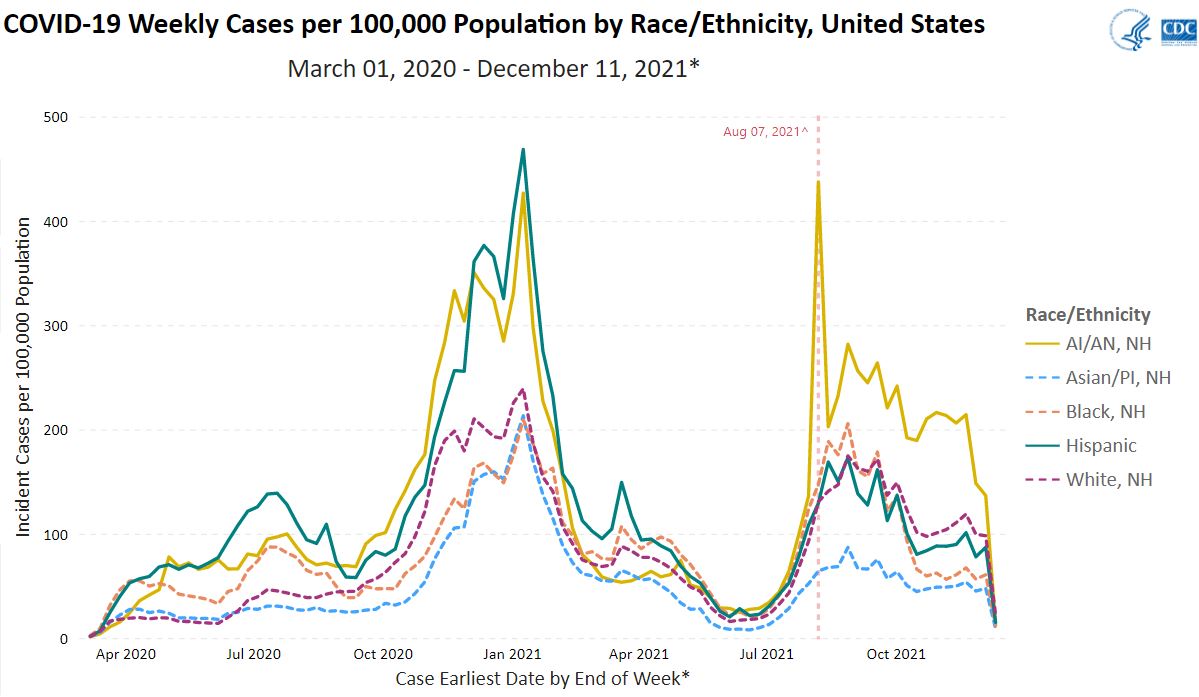

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, a federal agency, displays aggregated race data in its COVID-19 tracker, as of Thursday.

Asians comprised 5.8% of the total U.S. population, but only 3.1% of COVID-19 cases and 3.6% of COVID-19 deaths, according to the CDC tracker.

However, a September CDC report said, “aggregated race data can obscure health disparities among subgroups.”

Maryland’s COVID-19 dashboard also displays aggregated race data, as of Thursday, with Asians comprising over 14,500 cases and 355 deaths in the state – the lowest number of cases among the six racial and ethnic groups listed, and the second-lowest number of deaths.

Limited research reports on disaggregated COVID-19 datasets offer clues about disparities among Asian Americans.

In New York City’s public hospital system, disaggregated data suggested that South Asians had the highest rates of COVID-19 positivity and hospitalization among Asians — second only to Hispanics for positivity and Blacks for hospitalization — between March and May of 2020, according to researchers last year at NYC Health + Hospitals and New York University.

The South Asian group comprised Afghani, Bangladeshi, Indian, Nepalese, Pakistani and Sri Lankan people, the report said.

Additionally, Chinese patients had the highest COVID-19 mortality rate of all groups, according to the same report.

A peer-reviewed version of the report was not available online, as of Thursday. It is scheduled for publication in Public Health Reports, a peer-reviewed journal, this month.

A different report found that 4% of the country’s registered nurses were Filipino, but more than 31% of registered nurses who died of COVID-19 and related complications were Filipino, according to National Nurses United, a nurses’ union, in September 2020.

MARYLAND RESPONSE

For Maryland, “a good first step is to expand current racial identity categories on state forms to include opportunities for respondents to identify not only as Asian or Pacific Islander, but to indicate national origin as well,” said Janelle Wong, an Asian American studies professor at the University of Maryland and a researcher at AAPI Data, in an email to Capital News Service.

“Our Asian American elected officials are important actors when it comes to moving this pressing issue forward,” Wong said.

State senator Lam told Capital News Service, “We have considered it but do not have any legislation planned at this time,” as legislation would be difficult to update while understandings of Asian American and Pacific Islander communities improve and evolve, Lam added.

State departments and agencies can also adopt their own policies for data disaggregation and “we’d be open to working with them on developing provisions that address this issue,” Lam said.

“We are examining other states and their policies to address data disaggregation to see if there are methods or policies that we can adopt from them that have been effective,” Lam said.

YOUTH ACTION

Despite the lack of state legislation, high school students organized in Maryland to advocate for data disaggregation.

“Following the Atlanta shootings, we decided that we were going to put together a working group of Montgomery County students,” said Kelly Ji, a senior at Wootton High School in Rockville, Maryland, and president of the Asian American Progressive Student Union, or AAPSU.

The Atlanta shootings refer to a March 16 attack in Atlanta-area spas, where eight people – including six Asian women – were shot to death. A white man pleaded guilty to four of the deaths, months after people around the country mobilized for Asian civil rights.

“One of our biggest demands is data disaggregation. We’re pushing for that in our school system and in our county,” Ji said.

The students founded AAPSU in 2020 to promote racial equity in the Asian American community, according to the organization’s website, and executive board members collaborate across eight Montgomery County high schools.

Data disaggregation is “incredibly important for shedding light on overlooked racial and educational disparities … so we can create more individualized plans when it comes to these marginalized groups’ healthcare or education,” said Alex Nguyen, AAPSU’s policy and advocacy director and a senior at Springbrook High School in Silver Spring, Maryland.

“I’ve always felt detached from my Asian identity because my experiences were dissimilar from many others who were affluent,” Nguyen said.

“But learning that there were different groups even within the Asian diaspora led me to join AAPSU on behalf of other Southeast Asians who may not know about these differences,” Nguyen added.

The organization plans to send its formal list of demands to the Montgomery County Council and Board of Education this month, Ji said.

“As we’ve been meeting with county council members and other people, it’s gradually dawned on us how big of a task this is to undertake,” Ji said about pushing for data disaggregation.

“The amount of work it requires just means that it’s all the more important, because it’s so difficult to put into place,” Ji added.

The student group modeled its data disaggregation efforts on an approach that succeeded thousands of miles away in the Los Angeles Unified School District, Ji said, where the county’s Board of Education unanimously passed a resolution to disaggregate student data in 2019.

“L.A. Unified’s student data system has expanded from previously only 18 ethnic categories to now over 200 ethnic categories,” said Andrew Murphy, who advocated for data disaggregation in Los Angeles and works as director of policy and advocacy at the nonprofit Leadership for Educational Equity.

Over 40 nonprofits and community organizations helped pass what could be the most progressive policy in U.S. schools on race and ethnicity, Murphy said, adding that advocates were inspired by other data disaggregation efforts in Oakland, California.

“Data disaggregation only began gaining traction in California a few years ago, and it’s only now during the #StopAsianHate movement that innovative policies like data disaggregation are making (their) way to the opposite side of the country,” Nguyen said.

The #StopAsianHate movement refers to people rallying this year on social media and in person to denounce the increase in hate crimes against Asians during the COVID-19 pandemic.

More than 10,000 hate incidents against Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in the U.S. were reported to Stop AAPI Hate – a coalition that tracks and responds to hate incidents – from March 2020 to September 2021, according to a Stop AAPI Hate report in November.

“When our public institutions avoid disaggregating their racial data, they can offer their sympathy with the AAPI community as much as they want, but they will continue to systematically perpetuate the model minority myth and overlook individuals,” Nguyen said.