As the agency responsible for enforcing Title IX, the U.S. Department of Education collects data that should show whether high schools are providing equal athletic opportunities to girls and boys. Except it doesn’t.

Instead, the data the department gathers from school districts ignores some athletes — mostly boys — and often overstates girls’ participation in sports.

As a result, 50 years after the passage of Title IX, it’s still impossible to tell whether high schools are complying with the law unless someone complains. That burden usually falls to teenage athletes and their parents, who often aren’t aware of their rights under Title IX.

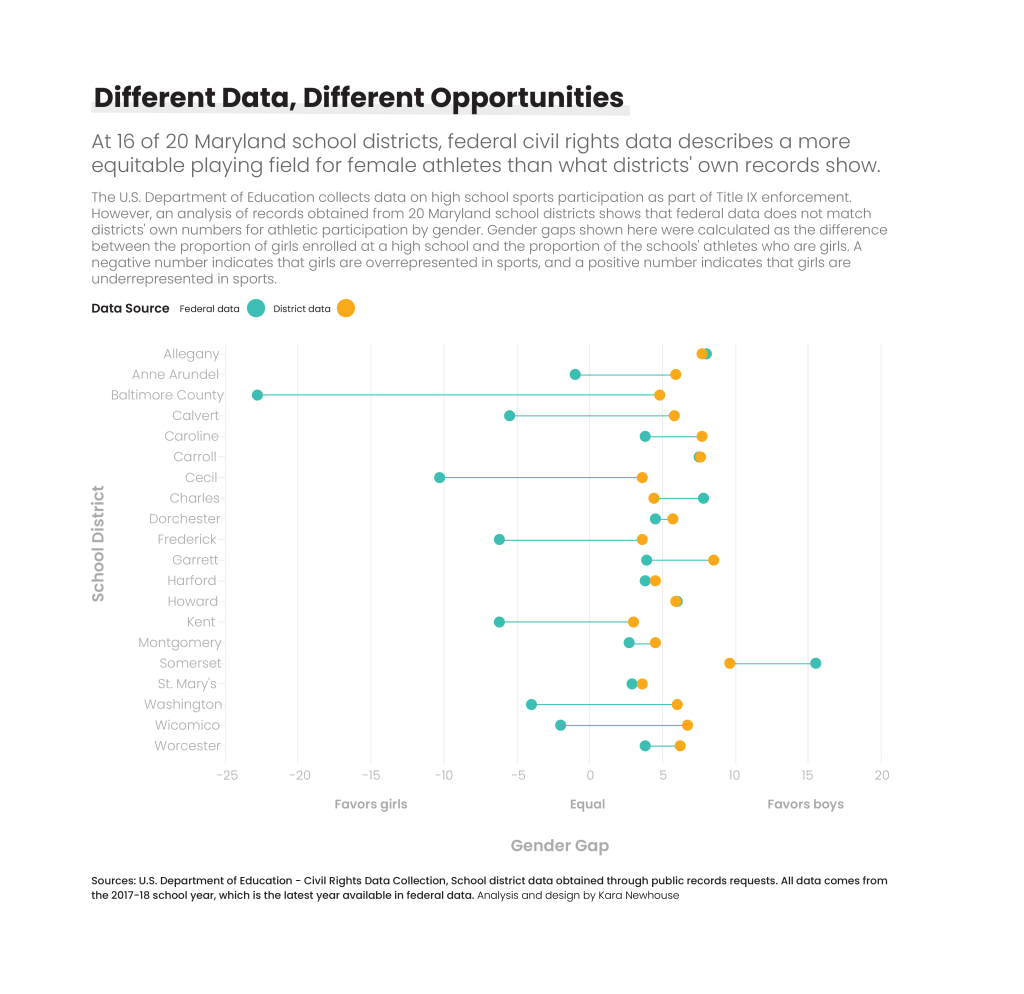

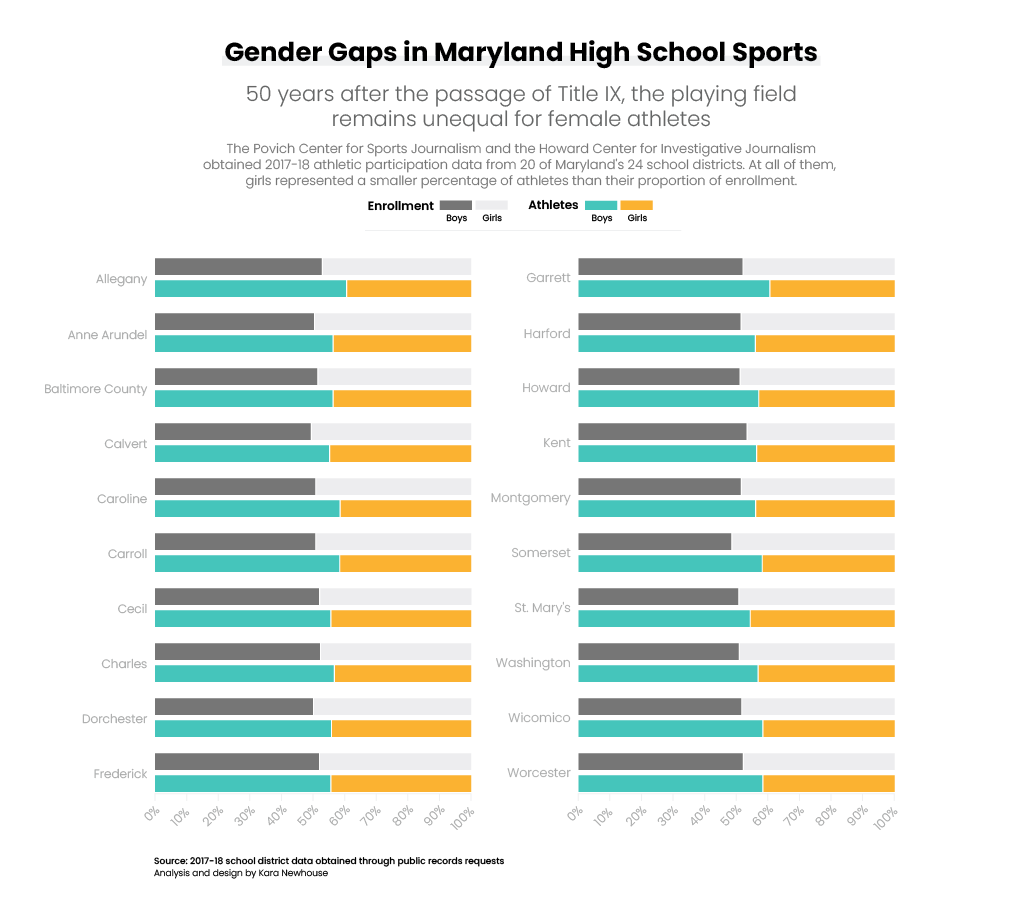

In a number of cases, figures collected by the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights are incomplete and differ substantially from statistics kept by school districts, an analysis by the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland shows.

[ Read more stories from “Unlevel Playing Fields” ]

The discrepancy seems to come largely from the office’s narrow definition of sports participation. Officials at several Maryland school districts, for example, said they don’t report complete counts of their athletes to the federal government because the survey asks only for a count of athletes on single-sex teams. Mixed teams — including football teams with one girl — are not included.

In an email response to the Povich and Howard centers’ findings, a Department of Education spokesperson said the public should not use its data alone to draw conclusions about Title IX compliance. He also said the department uses its data “in conjunction with other information and factors to investigate and enforce civil rights laws.”

Elizabeth Kristen is project director and senior staff attorney at Fair Play for Girls in Sports, a project of Legal Aid at Work that provides legal services to low-income families. She said that in high school Title IX cases she litigated outside Maryland, she’d seen that federal data didn’t reflect on-the-ground disparities. But she never knew why.

When told about the Povich and Howard centers’ findings, Kristen called the Office for Civil Rights’ exclusion of coed sports bizarre. “They’re not getting accurate information to help them enforce Title IX if they’re not collecting information about all of the athletic participants,” she said.

The office’s data comes from a survey that the agency describes as a “longstanding and important aspect” of administering and enforcing civil rights statutes. Under Title IX, schools are required to provide athletic opportunities in numbers that mirror each gender’s proportion of enrollment.

The Povich and Howard centers analyzed athletics participation at the 20 Maryland public school districts that provided usable data and found that, in all but four cases, federal data describes a more favorable situation for female athletes than what the districts’ own records show.

In fact, at about 40% of districts, federal data indicates that when compared to their proportion of enrollment, girls outnumber boys in sports. But schools’ own data tells a different story: All districts have fewer opportunities for female athletes.

In the large suburban district of Baltimore County, for example, federal data paints a picture of sports fields teeming with female athletes. The Office for Civil Rights’ public website says that, as of the 2017-18 school year, girls comprised 49% of enrollment in the district and 72% of athletes — making girls overrepresented in sports by 23 percentage points.

But the district’s in-house athletics data, which the Povich and Howard centers obtained through a public records request, says that girls actually comprised 44% of athletes, meaning they were underrepresented in sports by about five percentage points.

That’s one of several districts where the office’s instructions to count only single-sex sports teams distort the image of proportionality.

In Calvert County, a district spokesperson said its 2017-18 federal data submission did not include football, golf, wrestling, baseball and tennis because those sports were coed. According to district data, that means 616 boys and 54 girls were not counted. Federal data suggests girls are overrepresented in sports by six percentage points, but district data shows they are underrepresented by the same amount.

“I’m counting every athlete. Why wouldn’t you?”

When presented with the Povich and Howard centers’ findings, Title IX advocates said they were puzzled and flummoxed by the federal government’s exclusion of coed sports.

Peg Pennepacker, a longtime athletics administrator who now consults with high schools on Title IX compliance, said that’s not how she conducts athletics audits. “I’m counting every athlete,” she said. “Why wouldn’t you?”

A change could be coming. Proposed revisions to the 2021-22 survey would remove the single-sex distinction from the federal data collection. But the shift would only apply to new data, and those numbers would not be public for a few years.

In the meantime, Terry Fromson, managing attorney for the Philadelphia-based Women’s Law Project, said the available federal data isn’t fulfilling its purpose. “It isn’t making it easier for students or their families to find out if their children are being treated fairly,” she said. “And it should.”

Schools required to count, but only to count some

Since 2000, the Office for Civil Rights has required K-12 schools to submit data on various programs, including athletics, through the Civil Rights Data Collection. The office describes the biennial data collection as part of its “overall strategy for administering and enforcing” civil rights laws such as Title IX. According to a Department of Education spokesperson, the office “initiated 12 investigations in the last decade based in part on CRDC athletics participation data.”

The office also posts the data online, showing the gender breakdown of athletes side by side with enrollment percentages. The most recent data available is from the 2017-18 school year. (The latest data collection was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Title IX advocates said that most students and parents don’t know that they can check the office’s data tool to see whether their schools are providing proportionate athletic opportunities. If they did, though, the Povich and Howard centers’ analysis suggests that, in some cases, the data would not reflect equity gaps they see on their sports fields.

The Office for Civil Rights collects its data directly from schools, yet officials in many Maryland districts said they didn’t know why the federal data doesn’t match their own data. Those who had an explanation for the discrepancies pointed to the survey’s instructions to only count single-sex athletics.

Rob Willoughby, supervisor of instruction and athletics at Caroline County Public Schools, was one of those officials. Last November, he logged into the submission system to complete the latest survey. As he scrolled, Willoughby had questions of his own.

Like its predecessors since 2004, the 2020-21 Civil Rights Data Collection asked for the number of single-sex interscholastic sports at each school, the number of male and female teams and the number of female and male participants. The instructions said to “Include only interscholastic athletics in which only males or only females participate.”

Willoughby looked at the numbers for football. In the 2020-21 school year, no girls played on Caroline County’s teams. But Willoughby had coached football during years when the roster included a girl. He was unsure whether to report the sport as single-sex or coed. “Is it based on who actually participates?” he wondered. “Or the rules of who can participate?”

According to a 2020-21 data tip sheet for schools, when a girl participates on a predominantly male team, such as football or wrestling, the entire team should be excluded from the data. Since that can lead schools to exclude greater numbers of male athletes, it can result in the overall proportion of female athletes appearing higher than is the case.

For instance, if Caroline County’s football players were omitted in the last data collection from 2017-18, it would mean that 135 boys — or 15% of the district’s athletes — were not counted in the federal data.

Additionally, the exclusion of coed sports can mean that which teams get counted in a given district can change from survey to survey, since girls may participate in traditionally male sports one year and not others. That makes following trend lines difficult, Willoughby said. “It didn’t seem to me like they were collecting data to tell a story,” he said.

It’s difficult to know how school employees who complete the data collection interpret the single-sex athletics definition. Willoughby, who became athletics supervisor last year on top of another supervisory role, said that he tried clicking on a link in the instructions for more information about definitions, but it didn’t work. He asked his director for guidance and tried Googling the subject.

Ultimately, he included football in Caroline County’s 2020-21 totals since no girls had played that year. But he said it felt like a judgment call, and he didn’t know if “the people who sat in this chair before me did it the same way.”

Proposed changes in the count

A fuller picture of athletic participation could be coming. In December, the Department of Education shared its proposed revisions for the next data collection, which would eliminate the single-sex athletics questions and ask schools for a tally of all male, female or nonbinary athletes.

It’s unclear whether the Office for Civil Rights is aware of how the single-sex definition affected its past data. Documents in the Federal Register say that the proposed changes are intended “to reduce the reporting burden on schools” and lead to more accurate data on all athletes, “regardless of gender identity.”

“I think what this all signals is just lost opportunity,”

Kristen, the attorney who has litigated high school Title IX cases, said those revisions would be a positive step toward equipping schools and families to advance gender equity in sports. But she lamented that incomplete data has been the norm for so long. “I think what this all signals is just lost opportunity,” she said.

Kristen also said that the office could do more to educate schools and the public about the data. Pennepacker, the Title IX consultant who focuses on high school sports, agreed. She said the office could take its data “and really turn it into something that could be very useful for schools and parents.”

But school leaders might not appreciate a more complete view of high school sports participation being made public, Pennepacker said. “To be quite honest … I can see it being threatening to some schools, too, because it may expose inequities within their athletics program.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.