At James Campbell High School in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, the girls water polo team began a recent season after having had no access to a practice pool, according to a lawsuit filed by two players on the team.

At Buena High School in Ventura, California, the girls softball field was so strewn with rocks that balls routinely ricocheted dangerously at players. That was a far cry from the well-groomed diamond used by the boys baseball team.

At Falmouth High School in Falmouth, Massachusetts, boys and girls hockey teams play at the same local rink. The boys’ dressing room was a “palace”, according to a parent of a player on the girls’ team. In contrast, players on the girls’ team shared lockers and even a bathroom with players in an adjoining locker room.

Title IX is a federal law passed by Congress nearly 50 years ago. It prohibits sex-based discrimination at any school that receives funding from the federal government, including in sports programs. A four-month investigation by The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland found that Title IX has fallen short of its promise for girls playing high school sports: They’re stuck in an imperfect system that continues to favor boys in many ways.

At Claremont High School in Claremont, California, the girls’ softball field is in a city-owned park where restrooms for players also were used by neighborhood transients. The boys’ baseball diamond is on campus.

[ Read more stories from “Unlevel Playing Fields” ]

The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism reviewed 109 Title IX complaints filed with the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights related to high school sports. Many described substandard facilities for girls — shoddy maintenance, uneven fields, limited or no access to gyms and pools. Of complaints filed from June 6, 2012, to May 4, 2021, 44% cited differences in facilities between boys’ and girls’ teams.

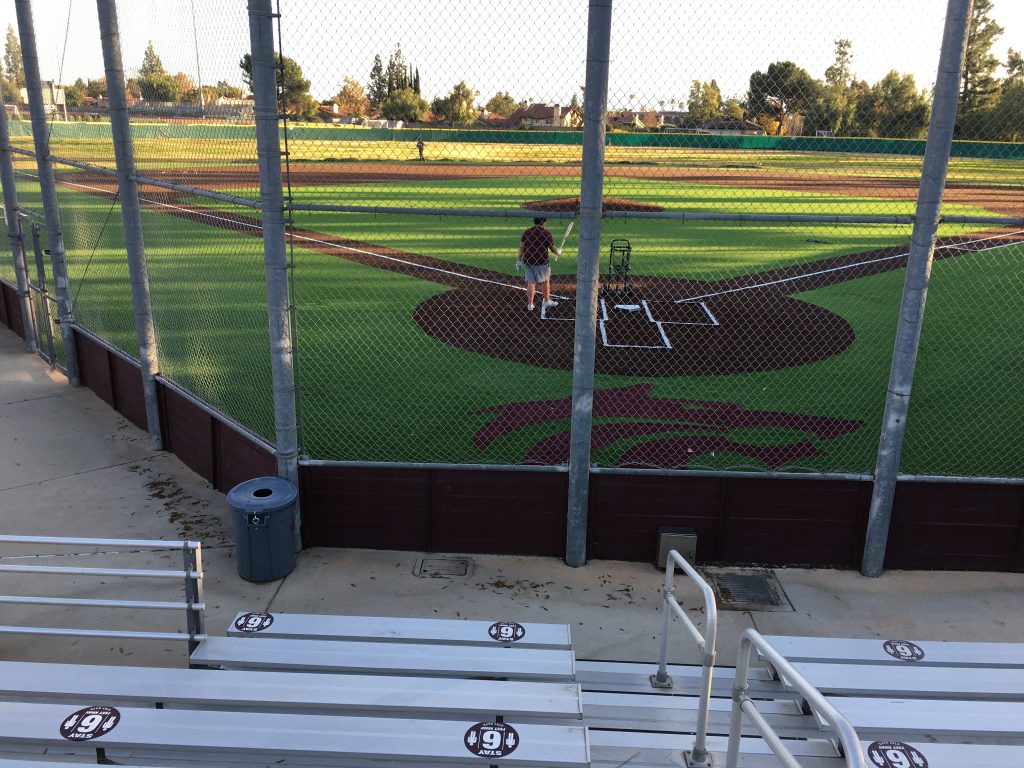

Travel from Claremont High School School in Claremont, California to Cahuilla Park, a city-owned field nearly three-quarters of a mile from the school.(Tim Jacobsen)

That doesn’t surprise Kayla Lombardo, lead editor for Softball America. “Unfortunately, it’s men who often decide where money and other resources get allocated,” Lombardo said. “So those men oftentimes, so not all the time, make decisions that benefit people who look like them, or have had similar experiences as them.”

The Povich Center examined four cases to learn about the concerns of students, parents and coaches.

Claremont High School, Claremont, California

Cristina Herrera had had enough. A mother of two softball players and president of the softball team booster club, Herrera observed a gap in resources between girls softball and boys baseball. In 2020, she filed a complaint with the Office for Civil Rights.

The Povich Center reviewed the complaint. In it, she describes a first-rate diamond for boys baseball featuring a scoreboard, covered dugouts, a clubhouse with a locker room, spectator bleachers, and multiple lighted batting cages. The girls’ field lacked those amenities.

The boys’ team had another advantage over the girls’. Its diamond was on school grounds, in contrast to the girls’ softball field, which was in Cahuilla Park, nearly three-quarters of a mile from the school. The distance from Claremont’s campus created issues of convenience and safety, according to Herrera. At the public park, she said, transients sometimes wandered into restrooms when team members were inside.

“The girls take no pride, honestly, like they play in a city park. You don’t give them something to be proud of and to strive to, you know, perform better,” Herrera said.

Because of Herrera’s actions and the Civil Rights investigation that followed, change is coming to Claremont High School. The school has committed to building a new softball field located near the varsity baseball team diamond. Under the resolution agreement, Claremont has promised the team a level outfield and maintained infield, a clubhouse that is equivalent to the varsity baseball clubhouse, equivalent lighted batting cages, an electronic scoreboard, a water-bottle filling station, and adequate spectator seating. The cost will be about $2 million, according to Kevin Ward, assistant superintendent of the Claremont Unified School District.

First pitch on the new field is expected in 2023.

Hanna Faiky believes that if she and her teammates had known about Title IX when she was a hockey player at Falmouth High School on Cape Cod, they would have spoken up.

“I didn’t even know about Title IX until I got into college. It was never expressed in high school.”

“I didn’t even know about Title IX until I got into college. It was never expressed in high school,” said Faiky, a 2021 graduate.

That information gap proved to be an obstacle for girls on the hockey team, particularly when it came to judging their facilities compared to those for the boys’ team. Falmouth Ice Arena is used by many hockey teams in the town of 31,500 people. On its website, the arena has displayed the locker room of the Falmouth High School boys varsity ice hockey team — a spacious, well-lit room with individual cubbies for player jerseys and other gear.

Images of the locker room used by Falmouth High School’s girls hockey team aren’t featured on the website.

Stacy Hostetter, mother of Jane Hostetter, a 15-year-old player on the girls varsity hockey team, described the boys’ locker room as “a palace.”

“The boys have…TVs, Xbox, mini-fridge…much nicer, and then the girls just have a regular locker room that has nothing,” she said. Improvements have since been made to the girls’ locker room, including updated decor, a rug and a new audio speaker, according to Jane Hostetter.

A complaint filed with the Office for Civil Rights in October 2020 stated that players on the girls’ team were required to share a bathroom with teams in an adjoining locker room, which was not always used by another girls’ team.

The shared bathroom, according to the complaint, could be accessed while players were showering. Some girls opted to shower in a bathing suit, or not shower at all, out of fear of being seen, according to the document.

As part of a voluntary resolution of the Civil Rights complaint, Falmouth High School agreed to conduct an assessment of its athletics program, which included an evaluation of the equality of locker rooms and facilities at Falmouth Ice Arena.

Contacted by the Povich Center, Falmouth High School officials declined repeated requests to comment about the complaint.

“It sucks, like we would always complain about [inequalities] to everyone,” Faiky said. “Over time . . . we had to get used to it and just live with it because nothing was going to change and it was awful.”

James Campbell High School, Ewa Beach, Hawaii

For the girls water polo team at James Campbell High School in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, something as simple as access to a practice pool became a challenge and cause for legal action.

A federal lawsuit filed in United States District Court against the Hawaii State Department of Education and the Oahu Interscholastic Association, triggered by a 2018 complaint, included several allegations.

For one, the Hawaii Department of Education failed to secure the team a practice pool until after the season started. The complaint alleges that the team played at least two regular-season games without a single minute of in-pool practice time. Instead, the program held practice on dry land and “open-ocean swim practices” at Pu’uloa Beach Park, according to the complaint.

The complaint also alleges a combative environment perpetuated by the athletics department over several years. At a game in the 2014-15 academic year, the school’s athletics director joked that “if the water polo program was going to lose, Campbell should not even have a water polo program,” according to the lawsuit.

In the lawsuit, the plaintiffs, who at the time were members of the girls water polo team, argued that the girls’ team had inadequate access to a pool, necessary for both practice and competition. While the state education department was eventually able to secure a regulation-size pool for the team two weeks into the season, it would not provide funding for the pool’s use. The team’s coach spent approximately $60 a day, two days a week, to use the facility.

The lawsuit also alleges that the state Department of Education and school administration retaliated against the team during a meeting by threatening to cancel the girls water polo season, “eliminate the team” from the athletics department or both.

“Every time I took ground balls, I would get hit in the face.”

Elizabeth Kristen, a senior staff attorney at Legal Aid at Work, also argued in September 2019 in front of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit that the school made it “very difficult” for a donor to give funds to the water polo program.

The lawsuit remains on appeal.

Buena High School, Ventura, California

At Buena High School in Ventura, California, safety was an issue. Upkeep of the softball field was so inadequate that players feared being injured.

“Every time I took ground balls, I would get hit in the face,” said Grace Saad, a former Buena High softball player. Saad added that she sprained her ankle twice from running in the outfield grass.

Boys’ baseball facilities were significantly better. According to the complaint filed with the Office for Civil Rights, the baseball field had a scoreboard, while the softball field did not. Players on the Buena softball team for years had to set up a temporary outfield fence before games while baseball had a permanent outfield wall, said former Buena High softball player Jenessa Ullegue.

“We didn’t have a fence for a while,” said former Buena High softball player Anna Brondos. “We had to fight to get a temporary fence put in.”

In 2017, the softball team went undefeated and won a state championship. After the season, members of the team approached Buena High’s principal to voice their disappointment about field conditions, Ullegue wrote in an email.

A 2020 agreement between the school district and the Office for Civil Rights mandated the district take action. The agreement required the school district to improve spectator seating, dugouts and bullpen areas at the softball field and to erect a scoreboard.

The softball field now receives more care. Dirt was added to the infield. Outfield grass is watered routinely. Raking of the infield regularly occurs after rain, according to Marieanne Quiroz, Ventura Unified School District’s communications coordinator.

“I have seen that there have been many improvements to the varsity softball field,” Ullegue, who has visited the school since the agreement, said in an email.

“I knew that things weren’t equal, but I just thought that’s the way that it was,” Saad said. “I didn’t think that there was really a point in saying anything because everybody loves football. Everybody loves baseball.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.