Over a month before police took him to prison in May 2016, dozens of anonymous Twitter users began threatening Kurdish journalist Nedim Türfent for his reporting on Turkish military operations in its Kurdish southeastern provinces.

On the day he was arrested, one user tweeted, “One should explode his ass with chemical weapon. Not a journalist, but a son of a bitch….”

The threats made Türfent’s colleagues at the now shuttered Dicle News Agency (DIHA) fear the worst. “When we found out that he was under arrest we were actually relieved because we knew he was alive,” Dicle Müftüogu, a journalist who formerly worked at the news outlet, told Capital News Service recently in an interview over an encrypted communications application.

Turkish authorities and armed Kurdish insurgents seeking an independent Kurdish state have fought one another since the early 1980s. Turkey has tried to suppress its Kurdish population by prohibiting the teaching of Kurdish language and culture and have imprisoned ordinary Kurds and journalists often erroneously link with the outlawed Kurdistan Worker’s Party (PKK).

Turkey, the European Union and United States have designated the armed guerrilla group as a terrorist organization for its attacks on civilians.

“The Turkish state wants to impose a crackdown on Kurdish [separatist] movements and they think that Kurdish journalists are engaging in [these separatist] Kurdish movements,” said Ismet Konak, a journalist with the Kurdish news outlet Mesopotamia Agency. “That’s why they always crack down on us.”

The Turkish Embassy in Washington did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

According to the U.S.-based press advocacy group the Committee to Protect Journalists, 18 journalists were imprisoned in Turkey in 2021.

Though Turkey is a U.S. ally and NATO member, its relations with the United States have been strained in recent years. To fight the Islamic State just across Turkey’s southern border in Syria, the United States partners with the Syrian Democratic Forces, a Kurdish-Arab militia that includes the Kurdish People’s Protection Unit (YPG). Turkey considers the YPG to be a terrorist organization because of its relationship to Kurdish separatist movements.

In 2014 Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became president and has been undefeated ever since. After a failed coup against him in 2016, he increasingly restricted independent media, promoted legislation restricting internet usage and periodically banned YouTube, Reddit and Wikipedia.

The government also imposed a state of emergency that lasted two years. During it, authorities closed more than 100 media organizations, including virtually all Kurdish outlets, according to the U.S. State Department’s most recent human rights report on Turkey.

“Just imagine our president in the U.S. filing a criminal complaint against everyone who insults him,” said Sierwan Najmaldin Karim, president of the Washington Kurdish Institute. “Speaking about the discriminatory policies or dictatorial approach by Erdogan will usually end up in imprisonment.”

THE ARREST

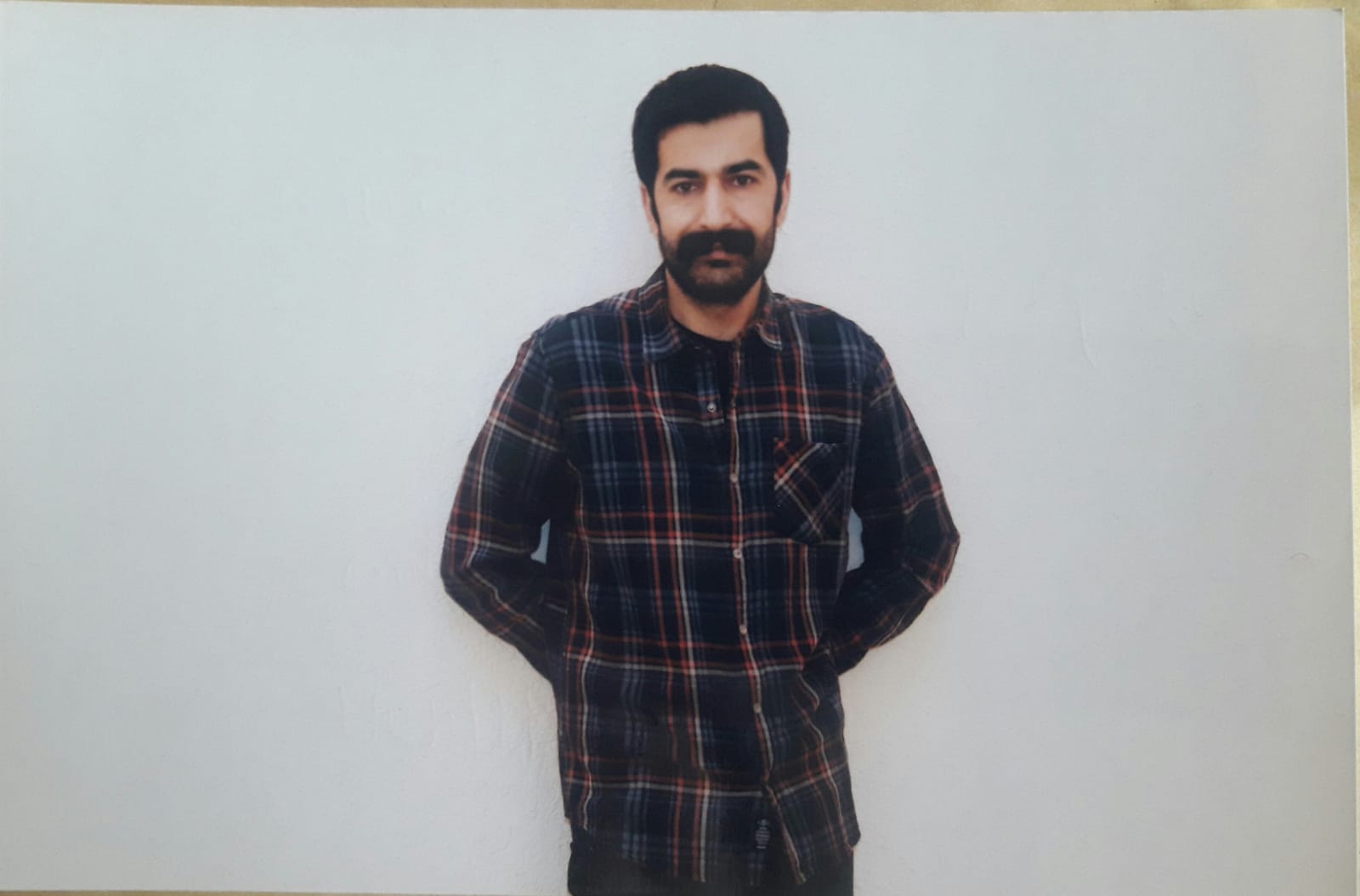

Türfent, now 32, was arrested six years ago after publishing a video of Turkish Special Forces shouting over dozens of handcuffed men in Yüksekova, a city in the southeasternmost Hakkari province, whose residents are predominantly Kurdish. “You will see the power of the Turk,” a soldier repeatedly shouted as the men lay face down.

Fourteen months later Türfent appeared in court for the first time.

Charged with membership in a terrorist organization, he was sentenced to eight years and nine months in prison.

According to the International Press Institute, a nonprofit organization dedicated to press freedom, the court said it ruled against Türfent because he “created news stories using exaggerated and disturbing remarks.”

But Türfent’s lawyer at the time, Barış Oflas, told the organization that 19 of 20 witnesses who testified against Türfent gave pre-trial statements they later claimed were made under duress and threats of death and rape.

No evidence other than these witness testimonies was used to convict Türfent, according to a legal report of the trial by the organization PEN Norway.

THE CONFLICT IN THE BACKGROUND

At the time of his arrest, the decades-long conflict between the PKK and Turkey had resumed in southern Turkey after a 2 ½- year ceasefire. Yüksekova was under a government-imposed curfew as the Turkish military conducted operations against the separatist group. Residents were largely restricted to their homes and subject to threats and violence by Turkish authorities, according to the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights.

The International Crisis Group, a Brussels-headquartered nonprofit organization that tracks global conflicts, reported that about 6,000 people have been killed in the regional conflict since 2015, including nearly 600 civilians. Many deaths occurred in the southeastern provinces where Türfent was reporting.

A 2017 United Nations report examining human rights violations in the region documented instances of housing destruction, excessive force by the Turkish military, curtailment of press freedoms and cutting off access to food, water and medical care.

“During the curfews, many journalists such as Nedim, who reported on the violations against their own people in Kurdish cities, were prosecuted and subjected to the violence of the police and soldiers,” Turkish politician Faysal Sarıyildiz, a member of the pro-Kurdish People’s Democratic Party (HDP), who lives in exile, told CNS.

LIFE BEHIND BARS

Despite his incarceration, Türfent continues to write. He contributed to the popular Turkish media outlet Bianet in 2021and was working with a New York University student to translate his writing into English when, in January 2022, he was stripped of his right to private meetings with his lawyers and others.

According to Bianet, Turkish authorities declared that corresponding with the student “may jeopardize prison security.”

Before these recent restrictions, though, Türfent published poetry through PEN International, a British free speech organization that has since translated his work into over 10 languages.

Experts do not believe Erodgen is likely to release independent and Kurdish journalists any time soon.

“He might suddenly release some journalist who’s a “cause celebre” in the West because he needs to appear a little more liberal,” said Alan Makovsky, a senior fellow at the liberal Center for American Progress who previously worked in the State Department’s intelligence bureau. “But I think the authoritarian course is set and, for Kurdish journalists, will continue to get worse.”