WASHINGTON – While the use of the death penalty has waned nationally, the Supreme Court has continued to give the green light for states to carry out executions.

The Supreme Court on Nov. 18 condemned an Alabama man to death in an order issued at 11:20 p.m. The late-night decision overturned a lower court’s stay of execution and allowed Alabama to proceed. As fate would have it, there would be no execution.

Alabama officials were unable to successfully administer the lethal cocktail of drugs to Kenneth Eugene Smith before his death warrant expired at midnight. Alabama’s governor then put a pause on executions.

Before reaching the Supreme Court, the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor Smith’s claim that there were issues with Alabama’s execution methods based on a previous botched execution. The Supreme Court overturned this ruling in the middle of the night without ever having heard full arguments.

As of Dec. 1, more people have been executed in 2022 than in all of 2021. There have been 17 executions so far this year. In 2021 there were only 11, which was the lowest number since 1988.

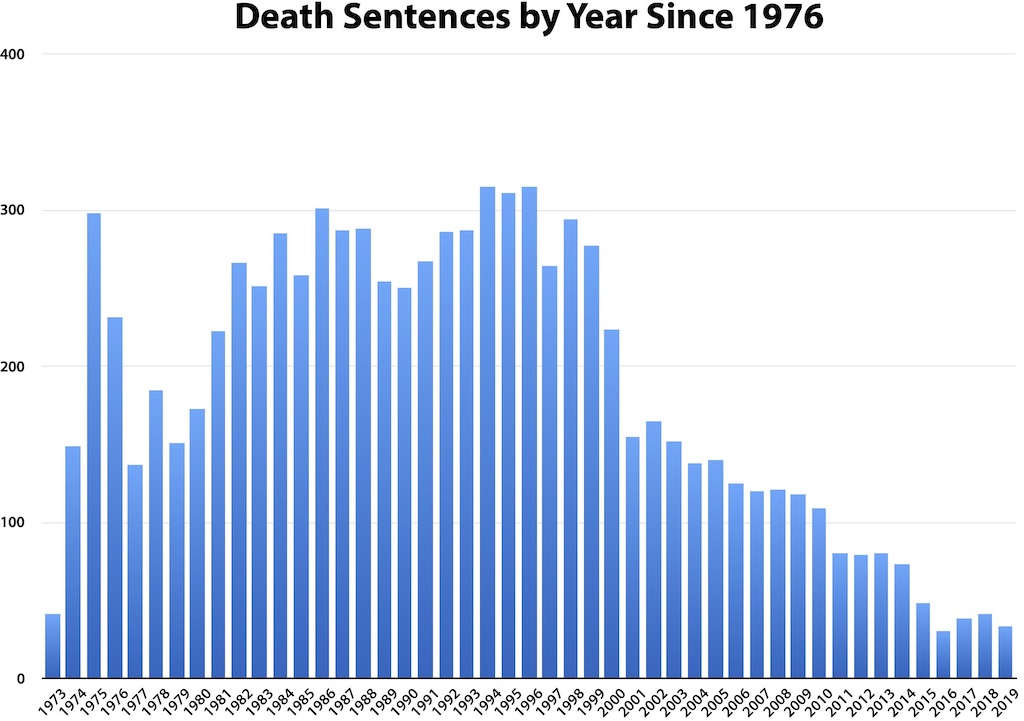

“What we’re seeing in U.S. executions and new death sentences is that there’s been a sustained decline in the use of the death penalty,” Ngozi Ndulue, deputy director of the Death Penalty Information Center, told Capital News Service. “Now, of course, executions are a lagging indicator of that decline, because we’re having executions of people who had been sentenced to death, decades beforehand, but overall, we see states just being less and less likely to resort to the death penalty.”

States planning on carrying out executions have faced significant hurdles in recent years as export restrictions have made it difficult to obtain the drugs necessary to carry out lethal injections and pharmaceutical companies have sought to avoid the negative public image associated with the drugs.

In 2011, the European Union banned the export of drugs like sodium thiopental, which it says “could be used for capital punishment or torture.” The reduced supply has led states to turn to less preferred drugs or to compounding pharmacies, facilities not authorized by the FDA, which mix their own chemicals on an individual basis.

“As soon as this issue became more prominent, no pharmaceutical company really wanted their drugs to be used for executions,” Ndule said. “They see it as not consistent with what the drugs were created for and also, I think they see some potential reputational harm if their drugs are kind of seen as the drugs that are used to kill people.”

The Texas Tribune has found that Texas, which is in many years the nationwide leader in executions, has only nine available doses of lethal injection drugs available. Texas currently has eight executions scheduled, but seven of the state’s nine doses are slated to expire on Dec. 8.

Activists hoped that the scarcity of lethal injection drugs would make executions unfeasible or lead to lethal injections being ruled in violation of the Eighth Amendment because of the unreliability of substitute drugs. However, the court has been largely unsympathetic to these claims.

In 2015, the court ruled 5-4 in Glossip v. Gross that the use of ersatz drug cocktails for executions was not unconstitutional because the death penalty is constitutional and it always contains a risk of pain.

Glossip established the standard that when convicts challenge a specific method of execution, they have to propose an alternative method.

Justice Samuel Alito wrote in the court’s majority opinion: “…Because some risk of pain is inherent in any method of execution, we have held that the Constitution does not require the avoidance of all risk of pain…After all, while most humans wish to die a painless death, many do not have that good fortune. Holding that the Eighth Amendment demands the elimination of essentially all risk of pain would effectively outlaw the death penalty altogether.”

Twenty-three states have outright abolished the death penalty and three more, California, Oregon and Pennsylvania, have governor-imposed moratoria.

The election of Donald Trump presented a change. The Department of Justice under Trump carried out a record wave of executions. In 2020, the Trump administration resumed imposing the death penalty after a 17-year moratorium.

The Trump administration carried out executions with unprecedented speed: between July 2020 and Trump’s leaving office in Jan. 2021, the federal government executed more prisoners than in the previous 56 years combined. Even days before President Joe Biden’s inauguration, the Department of Justice raced to carry out executions.

President Biden, for his part, has not resumed the federal execution moratorium, as opponents of the death penalty had hoped he would.

With the Supreme Court’s seal of approval, outlier states are continuing to forge ahead with executions. Oklahoma, for example, has scheduled 25 executions over the next two years.

However, the number of executions and death sentences is in decline. Even if the Supreme Court continues to sign off on executions, it may make little difference in the overall direction away from executions and death sentences.

“The long-term trend remains the same throughout the country. What we see is that outliers crop up,” Ndule said. “Some jurisdictions that are outlier jurisdictions will continue to try to execute and could end up with an outsized proportion of executions, while the vast majority of jurisdictions will have no executions.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.