The Shrine of the Little Flower church is a small parish in Belair-Edison in East Baltimore, but if residents from a struggling nearby neighborhood show up looking for help to pay an electric bill, they won’t be turned away.

“It’s easy to tell someone to dial 211, but that is like going down a rabbit hole,” said Joseph Martenczuk, the coordinator of music and liturgy for the church. “We try to identify resources that are available to them in the community.”

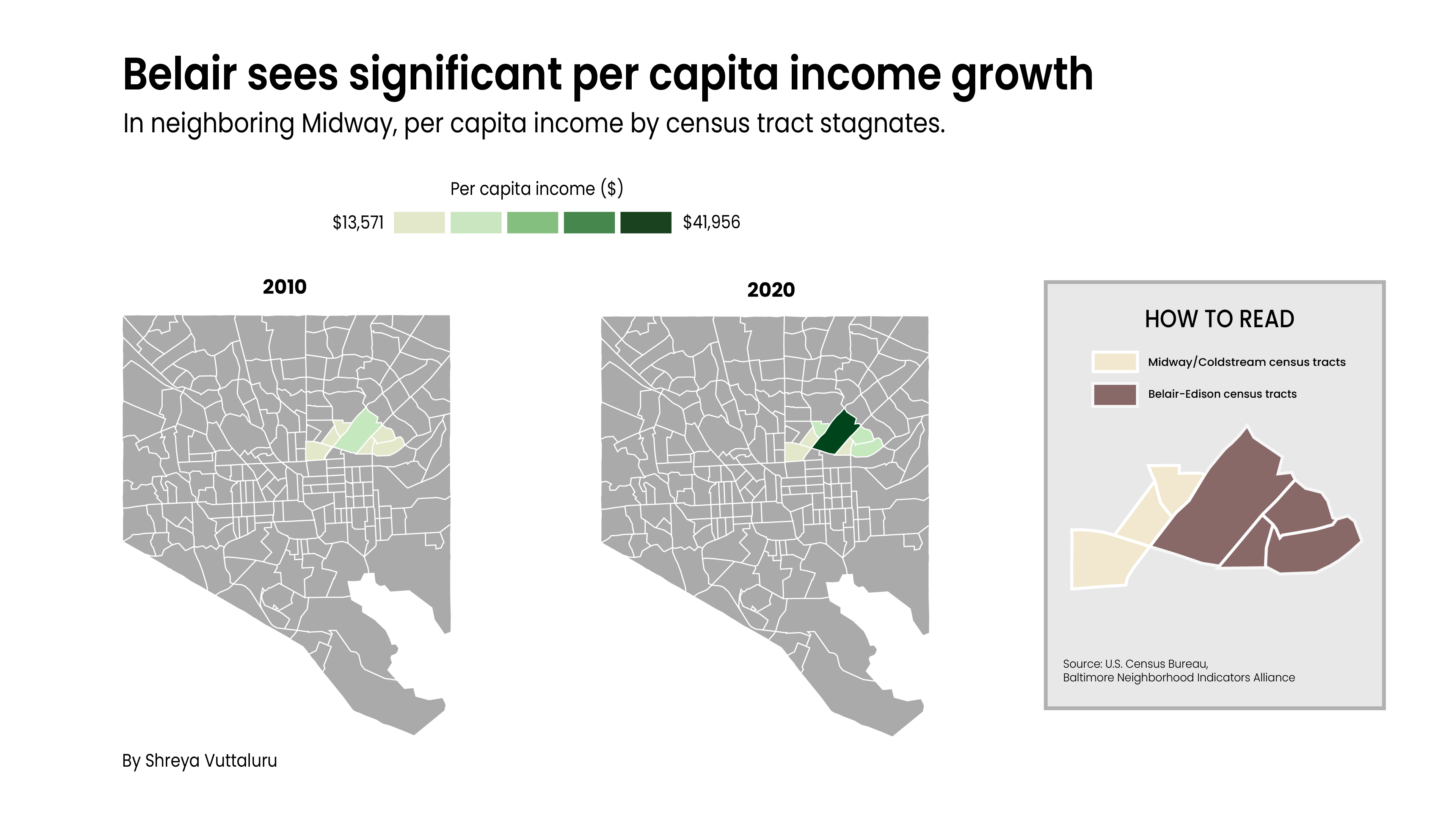

Belair-Edison isn’t one of Baltimore’s upper-class neighborhoods like Roland Park or Canton. Individual incomes top out at nearly $42,000 in 2020 for some, while others earn half as much, according to a Capital News Service analysis of census data. But neighboring Midway is much worse off, where the top individual income was $22,464, and many were below the federal poverty line of $27,750 for a household of four, according to federal poverty guidelines.

Martenczuk, 41, said the St. Vincent de Paul Society at the Shrine of the Little Flower church tries to help as many people as it can, but there are limits. They used to hand out $40 food vouchers to people in the community, but had to stop since it was costing the church too much money. If their church can’t help out, they will direct people to where they can get assistance, he said.

Still, the Shrine of the Little Flower church acts as a bridge for those trying to survive in a community growing in prosperity. Residents of the city appreciate the faith-based leadership and community-based activism. They feel that Baltimore has left them behind and in the dark.

Still, the Shrine of the Little Flower church acts as a bridge for those trying to survive in a community growing in prosperity. Residents of the city appreciate the faith-based leadership and community-based activism. They feel that Baltimore has left them behind and in the dark.

Community leaders are determined to improve their struggling neighborhoods on their own and are done waiting for the city to do something.

“Stop doing all the talking. If you’re going to talk, walk that walk,” said Roland Johnson Jr., leader of R&J Ministries of God in East Baltimore.

The need in Midway is great. A Capital News Service analysis showed residents in parts of Midway saw their incomes fall $533 between 2010 and 2020, while other parts of the neighborhood saw incomes rise by $5,474. That’s well below the citywide averages, where per-capita income reached $32,699 by rising $9,366 from 2010 to 2020.

Neighboring Belair-Edison fared much better. Per-capita income rose between $2,000 and $18,000 in the 10-year period, according to a Capital News Service analysis of census data. The reasons for the disparity between Belair-Edison and Midway are numerous, ranging from abandoned housing to lack of city investment, according to interviews. One major theme was the prominent role churches and faith leaders were playing to help build up these neighborhoods.

Johnson, 50, leads R&J Ministries of God, even though he has no physical church building and no car. Still, he tries to do whatever he can to give back to his East Baltimore community. This includes giving away clothes and food, which Johnson said he distributes from a wagon while walking around the Midway neighborhood.

Johnson said he does this with little to no help. Johnson and his wife Justina, 55, said they want support from the city not only for their own organization but for their entire community. Justina Johnson said she has called the city twice about recycling pickup and that no one responded.

“We got two houses in front of us that are empty,” Justina said. “People just throw trash like mattresses or chairs or whatever in the alley.”

Nearly 20% of properties in Midway are vacant and abandoned, according to the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA). By contrast, just 3% of properties are abandoned in Belair-Edison.

Another Midway activist, Kathy Christian, 53, said the city could do more to inform residents about “how to navigate the system.”

Christian, executive director of the Midway Community Development Corporation, said one common question involves what to do after your trash can gets stolen. A simple answer from the city could help with trash collection in the neighborhood. The city’s current communications system, which often requires people to navigate websites, is a barrier for elderly residents, she said.

“Just because someone doesn’t make a lot of money doesn’t mean they’re not intelligent,” Christian said.

Younger people feel challenges as well, said Charles Brown, 57, of the East Baltimore Graffiti Church. The high school completion rate for the area is 75% while citywide the rate is 78%, according to BNIA. In neighboring Belair-Edison, the graduation rate is nearly 82%. While there are now more opportunities for African Americans, there is still a long way to go for Brown’s neighborhood.

Brown, who has lived in Midway for seven years, said the school system is also failing its students by not teaching them important life skills regarding financial literacy such as renting a house or staying employed in a job.

Ellen Janes, 67, executive director for the Central Baltimore Partnership, said more programs for young people are a top priority. The partnership, which attempts to revitalize 11 neighborhoods including Midway, helped create a summer youth workshop, which included a session at The Voxel theater, where young people learned about the business and could create their own videos.

While The Voxel theater program drew younger teens, a bigger problem involves getting older youth to participate in organized activities.

“Kind of hate to say it, but they disappear,” Janes said. “They don’t come to community centers, they don’t come to community events and they’re not at school, so they’re tough to serve.”

Still, Janes is working to reach the older youth through various employment programs and career support.

The Central Baltimore Partnership is collaborating with community associations and nonprofits on other projects, such as creating community green spaces, creating youth programs, and supporting women- and Black-owned businesses. The group serves as a coordinator for about 100 organizations to work on these projects.

The Central Baltimore Partnership also runs a Community Spruce-Up program that seeks to revitalize community spaces ranging from restoring vacant lots to rebuilding playgrounds. One example is a community park project with Cecil Elementary School, which is located in Midway. The project will create two playgrounds, a sports field, improve stormwater mitigation, create an outdoor classroom for the school and create a new space for the community, said Aaron Kaufman, 33, the partnership’s community projects manager. The first phase of construction is expected to start in January, Janes said.

Support poured into the Midway community through the East Baltimore Graffiti Church’s Fall Festival on Oct. 29. Attendees received free meals, jackets and haircuts while their kids could play carnival-style games. Since it was a church-sponsored event, some activities required people to listen to a sermon before getting game and meal tickets.

Brown, the church’s pastor, seemed welcome at the event, with children running to embrace him.

Community leaders fault city and state officials for making poor investment decisions. For example, the state is building a parking garage on property in Barclay, a project that doesn’t help create ongoing jobs for the community, said Brad Schlegel, 72, from the Barclay, Midway and Old Goucher Coalition. He said the neighborhood instead needed better supermarkets since not everyone has access to a car and there are few good stores in the area.Instead, they got stuck with a parking garage.

“It seems like that is at the fait accompli, which the community didn’t really have a whole lot of input in,” Schlegel said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.