McElderry Park, a struggling East Baltimore neighborhood, is trying to turn around the community with a program that pays students to polish their basketball skills while preparing them for college.

Clarence “Ray” Askins, 17, is a senior at REACH! Partnership School and has participated in the YouthWorks summer program at the McElderry Park Community Association since his freshman year. Through this program, Askins is paid around $500 every other week for participating in a variety of college preparatory, leadership and basketball workshops. He also has to maintain a minimum GPA of 3.5. The goal is to win entry into the college of his choice.

“We get paid to better ourselves and have fun,” Askins said.

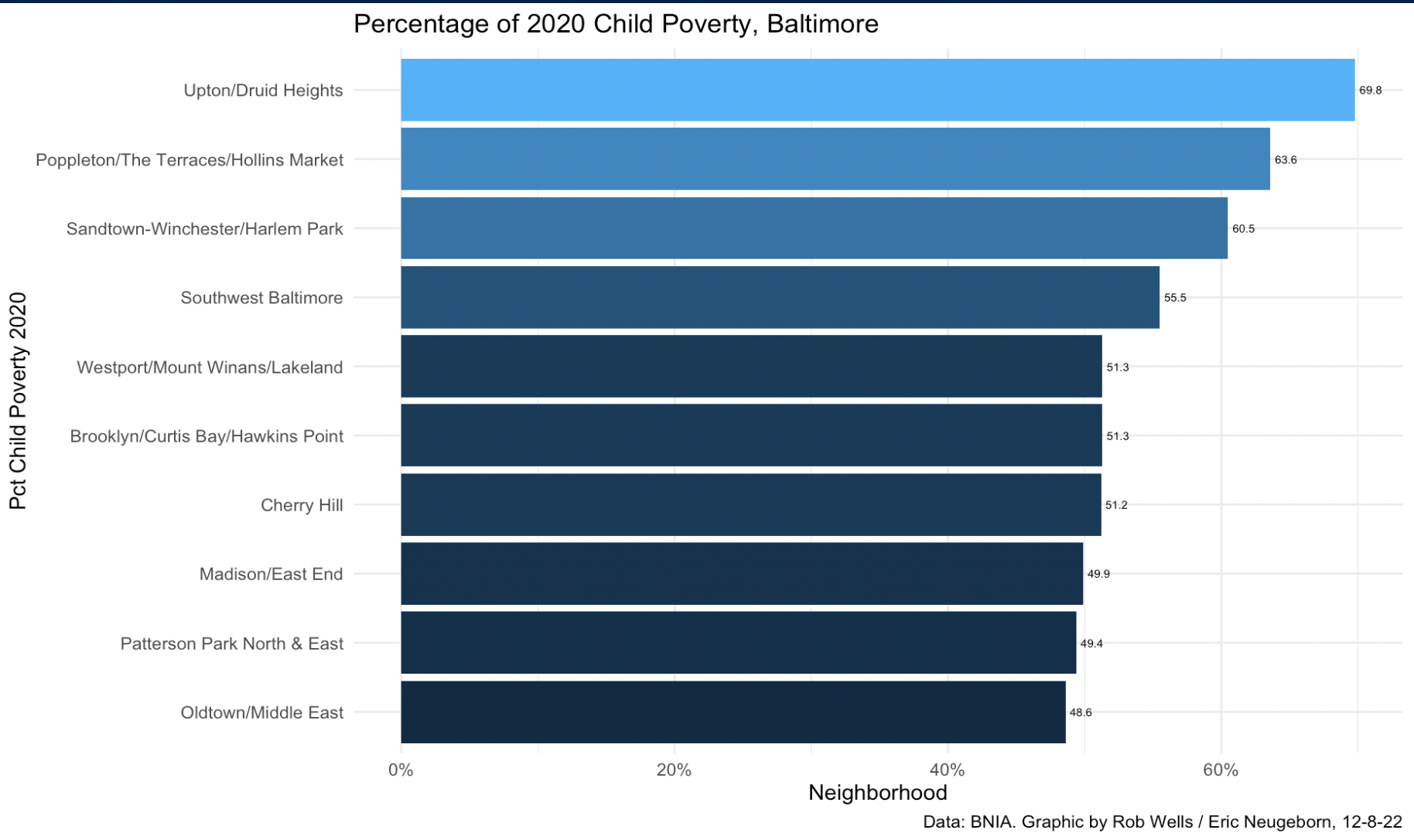

The McElderry Park Community Association, backed by funding from foundations, is trying to reverse a dire trend in its community. One out of every two children in McElderry Park is living in poverty, almost double the citywide rate, according to the Baltimore Neighborhood Indicators Alliance (BNIA). The high poverty leads to a decline in high school graduation rates and lower college attendance rates, according to the American Psychological Association. As of 2020, over 30% of students in McElderry Park did not complete high school, according to BNIA.

To address this need, the McElderry Park Community Association began youth council programs in 2015 following Freddie Gray’s death from injuries suffered in police custody, said Teddy Rosemond Jr., former McElderry Park resident and former vice president of the group. David Harris, the association’s president, said in addition to the SAT and ACT test preparation, the program will take the youth on college tours. “We help them with their enrollment package … scholarship money, whatever they need,” Harris, 52, said.

To address this need, the McElderry Park Community Association began youth council programs in 2015 following Freddie Gray’s death from injuries suffered in police custody, said Teddy Rosemond Jr., former McElderry Park resident and former vice president of the group. David Harris, the association’s president, said in addition to the SAT and ACT test preparation, the program will take the youth on college tours. “We help them with their enrollment package … scholarship money, whatever they need,” Harris, 52, said.

The student stipends are funded by YouthWorks, a Baltimore City organization, in partnership with the McElderry Park Community Association, said Rhonda McKinney, 51, program manager for the McElderry Park Community Association. Funding also comes from foundations, such as the Harry and Jeanette Weinberg Foundation, and the Johns Hopkins Office of Government and Community Affairs, Harris said. Other funding comes from work performed by the McElderry Park association, such as picking up trash and debris from construction sites.

Rosemond, 22, grew up in McElderry Park, and is a co-founder of the McElderry Park Youth Council and a former vice president of the group. Rosemond is now a software engineer and said his time working with the youth council taught him a lot of interpersonal skills that have helped him in his career.

“I was able to learn how to pitch myself, my purpose, my vision to apply for jobs,” Rosemond said. “I always wanted to help others and that’s kind of what I tie into my work now.”

Ernest Smith, 62, the McElderry Park Community Association treasurer, said the group wants to partner with nearby communities to expand these youth programs and “develop a hub through which we can support one another.” McElderry Park’s youth programs have also partnered with some schools outside of the neighborhood, including Patterson High School and Forest Park High School.

Askins said the paid stipend and SAT prep initially attracted him but he discovered the program had many more benefits. He recalled a guest speaker who described how he started from nothing and was able to turn his life around. “He’s a great mentor to the youth,” Askins said of the speaker. “He just [told] us how we can make it without being on the street.”

Askins said YouthWorks showed how he can be successful in Baltimore. He plans to attend college and return to give back to his hometown.

Askins highly recommends the program. “I don’t know why we don’t have a packed room every year,” Askins said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.