Old Town in central Baltimore, one of the three original settlements in the downtown area of the city, has seen better days. The neighborhood has a pedestrian mall that now has decaying buildings, giving it the feel of a ghost town.

Yet Erin MacDonald, who works for the Old Town Mall Merchants Association, believes there are a lot of misconceptions about the neighborhood.

“It just seems like this area gets lied about a lot,” MacDonald said. “There are a lot of times when I talk to people about this area and they’re like, ‘Oh I didn’t even know there were businesses open there. I didn’t know that anything was still thriving out there.’

“There are people living their lives here, and trying to run businesses.”

Instead of helping the Old Town businesses, MacDonald said the broader concern is “making sure they don’t get in the way of ‘progress.’ ”

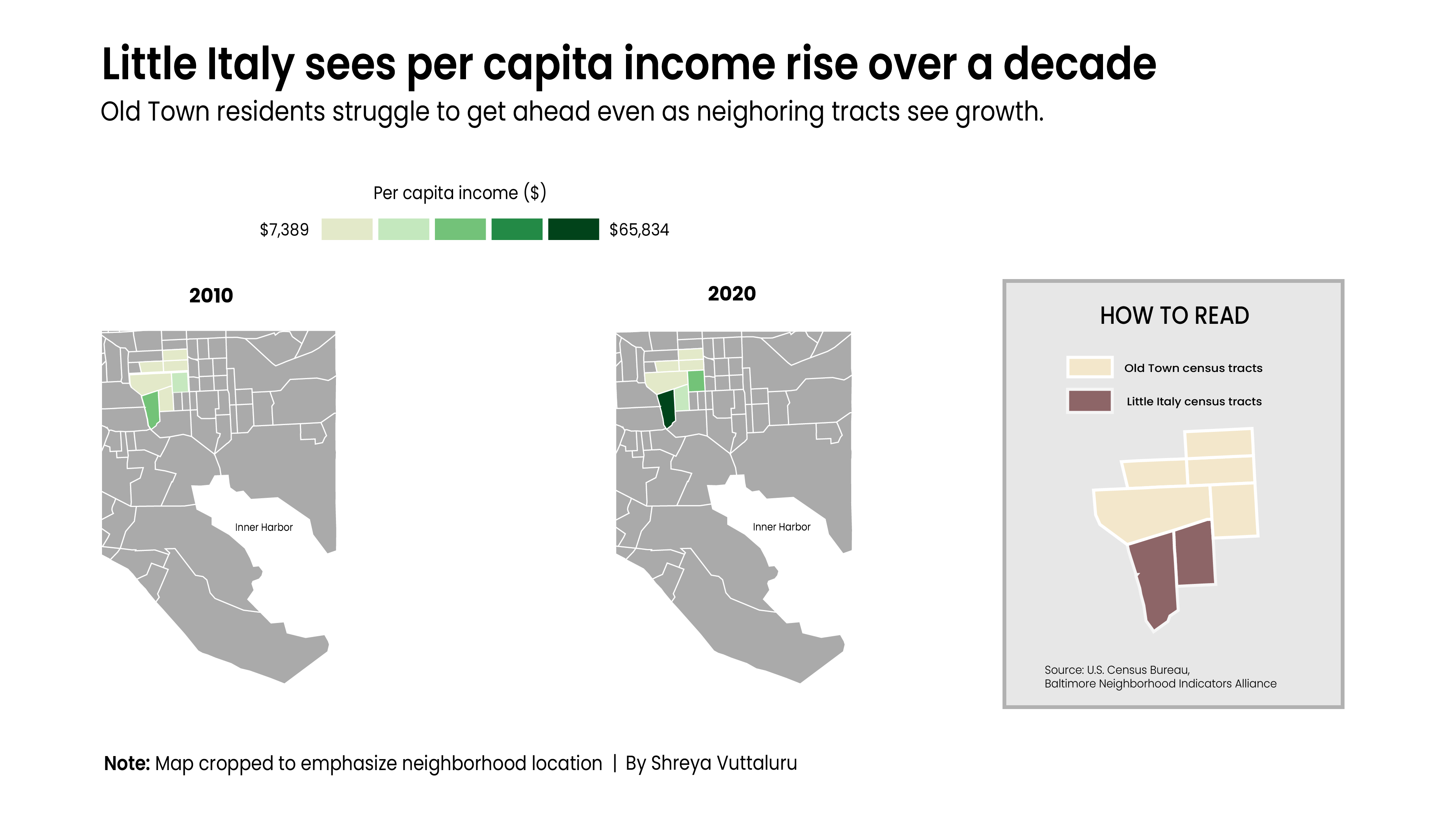

In the area around the Old Town Mall, the per-capita income was about $12,100 in 2020, below the federal poverty line. Residents in Old Town struggle much more when compared to surrounding neighborhoods such as Little Italy, where the per-capita income was more than five times higher at $65,834.

However, Old Town has a lot of history and is close to downtown. The city officials envision a redevelopment that includes new parks and commercial centers, although recent development plans have yet to commence.

However, Old Town has a lot of history and is close to downtown. The city officials envision a redevelopment that includes new parks and commercial centers, although recent development plans have yet to commence.

Old Town is home to about 9,000 people and consists mostly of rowhomes and multifamily buildings, with 86% of residents renting properties, according to Live Baltimore. The estimated average rent per month is $1,235 and the median home purchase price is $82,000. The Baltimore riot of 1968 occurred there as well, contributing to much of the area’s decline.

The Old Town Mall is a central feature. At its peak, the mall was a thriving shopping center with 64 stores, including Goldstein’s Style Shop, the Diplomat Shop and Kaufman’s, and was known as Gay Street, according to Atlas Obscura. After the 1968 riot, the revamped area was renamed Old Town Mall, and was restricted to only pedestrians. However, Old Town deteriorated by the 1980s due to unemployment and poverty, and census data shows it is one of the poorest parts of the city.

Wanda Watts, who represented the city’s health department on the steering committee for the Old Town redevelopment plan, sees wealth inequality as a struggle for the city. “It’s a historical problem. It’s not anything new. It’s been going on since the end of the Civil War, and it has not changed,” Watts said.

The lack of public transportation is one reason for the wealth disparity, Watts said. “We do not have a transportation system that will allow people to look for jobs outside of the city. They’re relegated to just looking inside the city unless you have a car,” Watts said.

MacDonald said redlining and gentrification are other causes of wealth inequality. MacDonald described “the continued segregation of poor into increasingly poor areas” and then a process of gentrification where development will serve “not the people who already live there but for wealthy people to either come back to the cities or retreat to the suburbs.”

Gentrification is a process that happens when wealthier people move into poorer areas and start changing the neighborhood by improving housing and attracting businesses, most of the time displacing some of the original residents. Redlining is a process that existed in cities to racially categorize neighborhoods, and although it was outlawed, the effects can still be seen in many places, including Baltimore.

Philip Leaf is a professor emeritus at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, said wealth inequality has many origins. “Everything from multigenerational violence and racism to young people having to look after their younger siblings, and therefore losing out on opportunities for themselves,” said Leaf, who also is on the board of My Brother’s Keeper Baltimore, an organization that focuses on empowering young men of color.

Leaf said a possible solution involves determining what systems and institutions perpetuate wealth inequality. To start, “you have to acknowledge there’s a problem,” he said.

Ron Miles, president and CEO of RJY Chick Webb Council, said the process of investing and building up neighborhoods is “definitely a slow, selective process, and not very equal.” The Chick Webb recreation center was one of the first recreation centers built for the city’s African Americans.

An example of this selective process is the Harbor East-Little Italy area. Development in Harbor East, an affluent waterfront neighborhood, spilled into Little Italy, said Doug Kendzierski, deacon at St. Leo’s church in Little Italy. As Harbor East developed, “it attracted a lot of diversity and a lot of young, urban professionals who are living there, which would necessitate a higher income,” Kendzierski said.

Little Italy, a historic neighborhood where Italian immigrants settled in the 1800s, is known for its strong Italian culture and traditions. Little Italy’s per-person income rose by $32,442 from 2010 to 2020, according to census data.

You must be logged in to post a comment.