The heavy rains from June to August in Umerkot, Pakistan, were shocking for an area that never receives enough. Allah Bachayu, a driver who lives in a mud house there, was caught off guard when the downpour came, and as the water rose, he grew worried.

“Everything was the opposite this time around,” Bachayu said in a recent WhatsApp interview from Umerkot. “People used to be happy when it would rain in the past.”

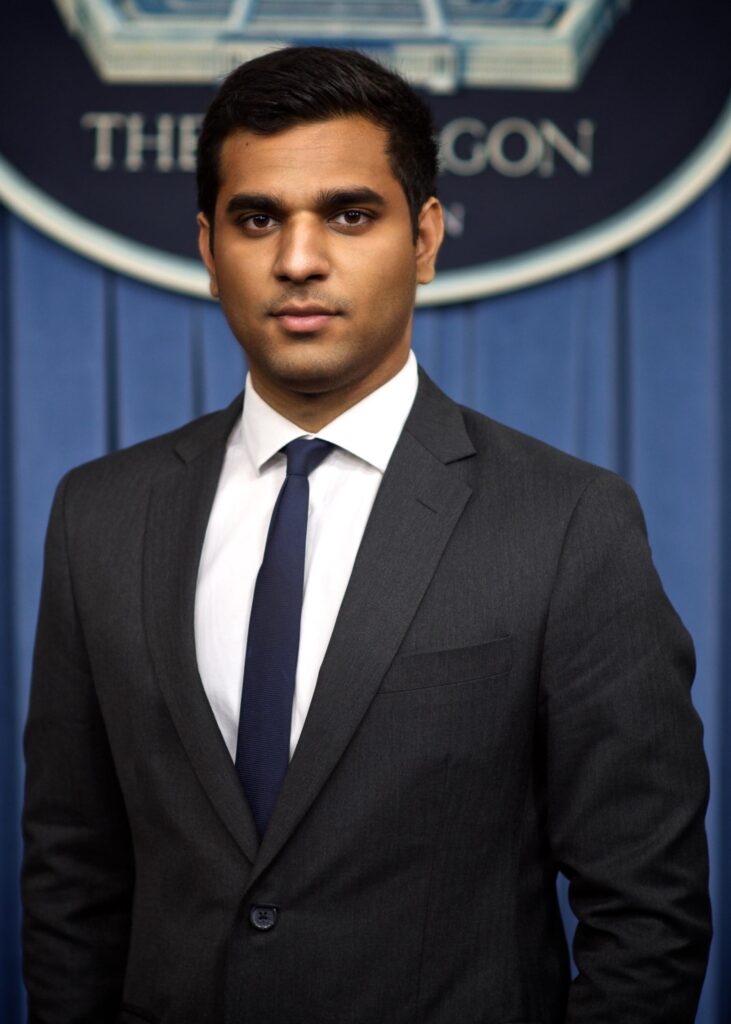

Bachayu had worked for the family of Idrees Ali, a national security correspondent for Thomson Reuters in Washington and an alumnus of the University of Maryland. Ali had been following news of the floods. But it wasn’t until he sat down for his weekly radio show on National Public Radio that he saw the floods were on the list of topics and realized their severity.

The same day, Ali, a Pakistani-born graduate of the Philip Merrill College of Journalism, saw satellite images of new lakes that had formed in places near his hometown of Karachi. Only at that moment, he said, did the level of destruction fully hit him, and he wondered how Bachayu, his family’s former driver who lived in the neighboring district, was doing.

“I cover the Pentagon and the military side. To a certain degree I’m desensitized to a lot of stuff like that,” Ali said in a recent interview with Capital News Service. “But knowing that it’s happening at home adds another layer of just disbelief.”

As the floodwaters rose about 5 to 10 feet over the course of a month, the mud houses in Bachayu’s village absorbed the water, then began falling apart. The walls collapsed first. The government and military were able to divert the water from reaching the shops and the center of town, but most houses that were not on higher ground were destroyed, Bachayu said in the interview, which Ali translated from Urdu.

About 90% of the livestock died, and diseases from mosquitoes, diarrhea and dehydration killed many children in a nearby village, he said. Bachayu’s brother was a farmer. Now he has lost his crops and his children are sick.

Roughly 1,500 people were killed and 30 million displaced in search of shelter and clean drinking water in a disaster that many experts attribute to climate change. Despite its tiny contribution to the world’s greenhouse gas emissions, Pakistan is one of the most susceptible to the effects of climate change, according to a United States Institute of Peace study.

Over the course of 20 years, 173 extreme weather events have been responsible for the deaths of 10,000 Pakistanis and financial losses totaling $4 billion, according to the Institute.

The U.S. pledged an additional $30 million in relief to Pakistan in October, bringing the total disaster-related assistance to $97 million. Other organizations such as the Saharo Foundation, based in Ellicott City, Maryland, and Islamic Relief USA initially responded with emergency efforts with donations of food, mosquito nets, tents and other supplies, representatives of the groups said.

Both organizations have recently shifted to helping rebuild houses and other rehabilitation projects to help Pakistani civilians, though some remote villages are still struggling four months after the disaster, they said.

Since 2005, the Saharo Foundation has worked with partner organizations in Pakistan to provide relief during natural disasters, gaining support from the South Asian community in Maryland through a GoFundMe page, donations from businesses and from a musical night starring an Indian singer, according to President and CEO Hanif Sangi, an Army veteran who founded the organization.

Anwar Khan, president of Islamic Relief USA, said that a funding shortage was the biggest obstacle to delivering enough food. Working with Islamic Relief for 29 years, he has made numerous aid trips to Pakistan and said he now worries that 2 million people will face starvation due to food shortages and increased prices.

“My feelings were of exhilaration when we were helping and shame that we didn’t do more,” Khan said in a recent interview with CNS.

The poorest people were affected the most, Khan said. Losing their livestock and crops meant losing everything, since many do not own the land they work on. In some areas, there are no official records for people without birth certificates, so their deaths will not even be counted.

As soon as the monsoons started this year, Bachayu moved to higher ground near the desert with a group of neighbors. The journey took one or two days. They set up a camp before he came back for his wife, daughter and parents.

Now that the flooding has receded, he is in the process of rebuilding his home, moving slower than usual since there is still floodwater in the area where they get the mud.

A tent city spanning about 3 miles on Umerkot’s outskirts was built for some 70,000 homeless families, mostly from the Sanghar, Mirpur Khas and Umerkot districts seeking refuge near the desert, according to the Pakistani-based newspaper The Express Tribune. The Saharo Foundation set up three medical tents in Umerkot, Sangi said.

“A few of our districts were really wiped out. Roads were closed,” Sangi said. “Those were the areas we were more focused on and we had to run some boats to reach the people in those areas.”

Pakistan is the fifth most populous country in the world yet also one of the poorest,

with 22% of people living under the poverty line and about 63% living in rural areas.

Amid social unrest and political conflict this year, Pakistan experienced extremely high temperatures in the spring, which led to record-breaking rains, since hot air can store more moisture. The monsoons, combined with water from melting glaciers, led to the flooding.

Shehrbano Jamali, a management consultant who lives in Islamabad, the capital city, said she returned to her village in Jafarabad with the Global Shapers organization to provide relief in Balochistan, an already marginalized province. She said nobody knows how to prepare for the unpredictable nature of flooding and climate change, so rehabilitation efforts are moving slowly.

“But when you’re up there, when you have to make a decision between families of who you’re going to be giving the last bag of food distribution to, I think that is ultimately where you really have to reflect,” Jamali said.

Feeling deep sadness, she said, it took emotional and physical strength to keep working as people tugged at her scarves or tried to trample her as they begged for food for their kids. Despite legal barriers to using foreign funds in relief efforts and people making politicized relief donations to different parties, Jamali said she and other volunteers are doing the best they can.

Most flooding and damage occurred in the southeastern provinces of Balochistan and Sindh. Sindh, where Umerkot and Karachi are located, was the worst affected area, receiving 466% more rain than average in July and August. About one-third of the country was under water when United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres visited. He said he had never seen this level of climate carnage.

Guterres called for global support, especially from wealthier nations that contribute more to global emissions. According to The World Bank, damages and losses totaled over $30 billion and rehabilitation will cost about $16 billion if new structures are to be resilient against future disasters.

Pakistan is also facing an economic crisis exacerbated by the floods, with sagging global markets, low foreign exchange reserves, high inflation and a political system in deadlock.

The country has about $130 billion in external debt, of which about $30 billion is owed to China. In August, the International Monetary Fund approved a $1.17 billion bailout program, but talks between Pakistan and the IMF about other debt are still ongoing.

The government is grappling with corruption too, which affects all aspects of the social and political landscape while Pakistani civilians struggle. Power is shared with the Pakistani military, which has rarely been held accountable for its ties to corruption cases.

Former Prime Minister Imran Khan was once well liked by the Pakistani military, but eventually they had a public falling out over senior military appointments and policy decisions. Khan was ousted from the government by a vote of no-confidence in April and since then has launched a campaign to return to power, holding massive rallies where he also criticized the military, leading the government to attempt to ban his speech livestreams.

Unprepared to respond to monsoons of this scale, the government attempted to provide flood relief aid, but the services were limited. Still civilians in some villages are struggling while volunteers and citizens worked to mobilize to bring relief to affected communities that have not received help.

Because of the flooding, the national poverty rate is expected to increase by up to 4%, according to The Express Tribune. Such an increase could mean an additional 9 million people will live in poverty.

“It’s a vicious cycle: it happened and since you’re not well off, you can’t do anything and then it happens again and you’re less well off,” Ali said. “I think the bigger issue is not just the flooding, it’s the fact that meaningful change isn’t taking place in the way these areas are going to be rebuilt after the flooding.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.