WASHINGTON – While the teaching of Black history is under fire and facing censorship in some states like Florida, two Maryland lawmakers have proposed legislation aimed at providing more federal support to promote and preserve Black history, culture and education.

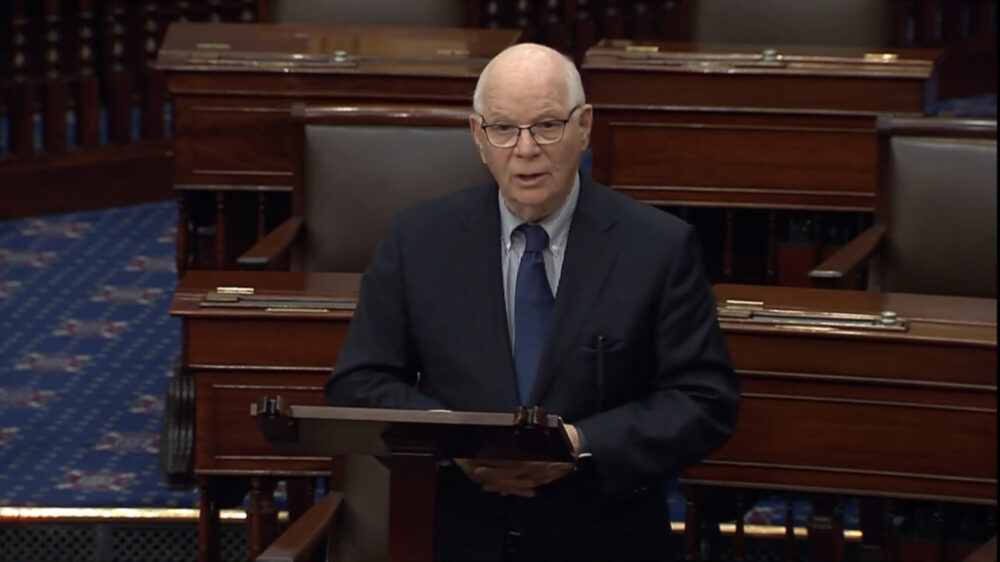

Rep. Kweisi Mfume and Sen. Ben Cardin, both Maryland Democrats, introduced their measures on Feb. 1, the first day of Black History Month.

The legislation would create a council of 12 presidential appointees to advise the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) on promoting Black voices, ensuring that Black history and culture is recognized in schools, providing resources to preserve Black history, and recommending national policies that would generate improved public understanding of African American history and culture.

“African American history is American history,” Cardin said in a statement. “For too long our history lessons failed to fully acknowledge the role of Black Americans. And it happens in far more places than schools – so much of what we have learned for generations about history, music, culture and more has diminished the role of African American creators, writers, musicians and beyond.”

“This bill pushes back against the attacks on African American history in our schools and communities,” Mfume said in a statement. “We must ensure that Black history is told fully and accurately in America. While the truth of our journey may not be the easiest to tell, it should be protected and celebrated because the story of African American people is intricate and integral to the story of the United States of America – that history must be treated and admired as such.”

School courses on African American history are generating political controversy. A new Advanced Placement African American studies course, which is currently being piloted across the country, has come under fire recently.

Gov. Ron DeSantis, R-Florida, and the Florida Department of Education attacked some of the topics being covered in the course, including so-called critical race theory and the Black Lives Matter movement.

The AP course’s official framework has since been revised. Supporters of Black history education claim that texts by scholars focusing on critical race theory have been removed from the course and that essential topics were left out. According to a statement from the College Board, however, no such changes were made.

“We must also clarify that no Black scholars or authors have been removed from the course. In fact, contemporary scholars and authors are never mandated in any AP framework,” the College Board said in a Feb. 8 letter to the Florida Department of Education.

The College Board also wrote that no topics were removed because “they lacked educational value.”

In an updated statement on Feb. 11, the College Board said it should have been more clear about the framework and topics of the course, differentiated between the final curriculum and the early framework, and denounced the Florida Department of Education’s “slander” of the course.

The course is being piloted in Maryland at the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute, part of Baltimore City Public Schools, and is one of only 60 schools in the country participating in the pilot program during the 2022-2023 school year.

In a Feb. 1 tweet, Cardin wrote that he was proud that the course is being piloted in Baltimore.

“Any kind of censoring or shielding students from #BlackHistory is a disservice to our nation & the people who came before us. Black History IS this nation’s history,” the senator said.

As of December, 31 students were enrolled in the AP course, according to Dennis Jutras, coordinator of Gifted and Advanced Learning at Baltimore City Public Schools. The district has not received any direct responses from students or families regarding the course, which “is typically the case when things are going well,” he said.

“The problem is that traditional history classes do not give equal bandwidth to all voices,” added Jutras, who taught AP U.S. History for nine years. “AP African American Studies – what it’s doing is trying to balance the equation and giving a greater bandwidth to part of U.S. history that is oftentimes neglected.”

Jutras said the legislation proposed by Cardin and Mfume would have minimal impact in Baltimore City schools.

“I definitely see a need for it in maybe some other districts in the state of Maryland,” Jutras said in an interview with Capital News Service. “And, of course, if national legislation would follow, there’s certainly states that could use those kinds of protections, but in Baltimore City, we have a long history of genuinely appreciating academic freedom.”

At a hearing earlier this month by the House Education and the Workforce Committee, Virginia Gentles, director of the Education Freedom Center at the Independent Women’s Forum, a conservative nonprofit, said she “absolutely” supports the teaching of African American history in schools.

However, she added: “I don’t think from a federal perspective that Congress needs to get involved in what a state should or shouldn’t teach. That isn’t the role of the federal government.”

During the hearing, Rep. Aaron Bean, R-Florida, defended his state’s choice to restrict the teaching of critical race theory.

“Let’s teach subjects that matter, reading, writing, arithmetic. The so-called CRT, (critical race theory) we’ve said ‘no’ in the state of Florida, ‘no’ to CRT. There’s no value. There’s no value to teach kids to hate each other based on race. There’s no value in teaching kids to feel guilty just because they’re of a certain race,” Bean said.

Rep. Susan Wild, D-Pennsylvania, countered: “CRT, otherwise known as critical race theory, is not taught in K-12 schools ever. This is a talking point that has been used by the opposition party to try to inflame parents and people and it is simply not done, and we need to stop talking about it.”