WASHINGTON – Congress has begun deliberations on how to improve federal law governing the response to public health crises like the COVID pandemic that killed more than 1 million people in the United States alone.

“To be honest, as Americans, we can understand that every public official tried their best during this COVID (crisis),” Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-Vermont, chairman of the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee, said at a public hearing earlier this month. “But the truth is that we were very, very unprepared for what hit us three years ago. It took a lot longer for us to respond to that emergency than it should have.”

A 2006 law intended to provide necessary resources for such a crisis expires Sept. 30 and needs to be reauthorized. Lawmakers have asked public health officials, doctors, hospitals and scientists for suggested changes that would improve the response to a future pandemic.

Sen. Bill Cassidy, R-Louisiana, said the current law’s framework proved to be far from perfect during the COVID pandemic.

“The government clearly failed consistently and clearly failed to communicate with the public,” Cassidy said. “Let’s update the playbook and make sure whatever we do it’s flexible enough to address the threats beyond just a pandemic.”

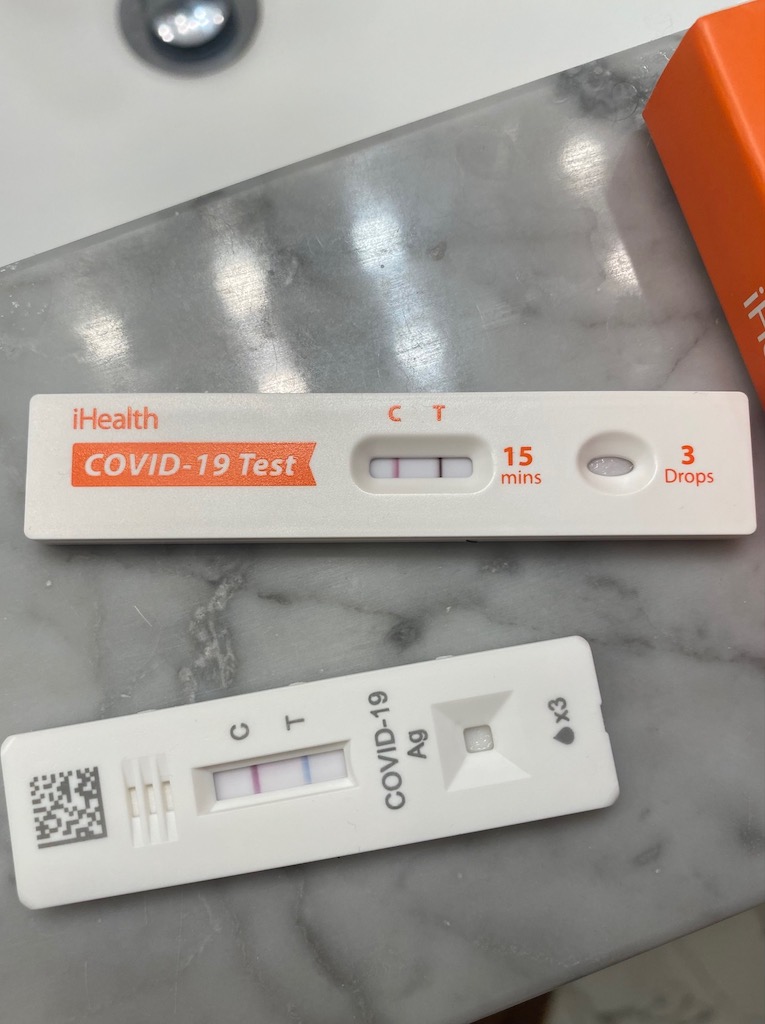

The American Society for Microbiology said in a statement that the reauthorization is an important opportunity to “improve our nation’s ability to respond in a timely and coordinated manner” to future public health threats. The ASM wrote that labs in particular would play a significant role in the early stages of pandemics for testing and studying diseases.

Before the pandemic, the CDC had 187 health facilities and now has 25,000 facilities to manage statistics and data. The agency is asking for clear data from states regarding vital statistics and death registries that are currently only provided voluntarily, according to Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“If we are supposed to stop disease outbreaks before they start, before they become emergencies, we have to have line of sight as to when those urgent issues are sparked,” Walensky said.

Walensky said it took six months to get hospitalization data during the pandemic. She said that making the data more accessible would allow Americans and policymakers to make more informed decisions with the resources available.

Dr. Reshma Ramachandran, an assistant professor of medicine at Yale University, said the reauthorization needs to negotiate a ceiling price for vaccines to protect patients from anticipated price hikes by major companies.

“While Moderna executives became billionaires, taxpayers were price gouged,” said Public Citizen President Robert Weissman. “Hundreds of thousands or maybe millions of people lost their lives because we had a global shortage of a vaccine that could have been avoided.”

Weissman said that to prevent these companies from making decisions for profit, starting prices must be determined by the United States not paying more than other high income countries. He said that life-saving vaccines deserve to be shared with everyone to save their lives.

Ramachandran said it is frightening that patients could still not be able to afford a publicly-funded vaccine once the pandemic period ends.

“No one should be poor because they’re sick and no one should be sick because they’re poor,” she said.

Moderna CEO Stephane Bancel told the Senate committee in March that his company would make sure cost would not prevent anyone from getting the vaccine.

During the pandemic, there was a heavy reliance on imported PPE, Sen. Bob Casey Jr., D-Pennsylvania, said at the hearing.

Dawn O’Connell, assistant secretary for preparedness and response at the Department of Health and Human Services, said there has been $16 billion dedicated to creating PPE in the country, but the ability to continue to do so must be maintained through the reauthorization.

As part of the reauthorization, Walensky said the CDC would also ask for new funding, including danger pay for healthcare professionals, tax-exempt loan repayment options for their education and overtime pay increases. These incentives are intended to hire professionals for the 80,000 unfilled public health jobs, according to Walensky.