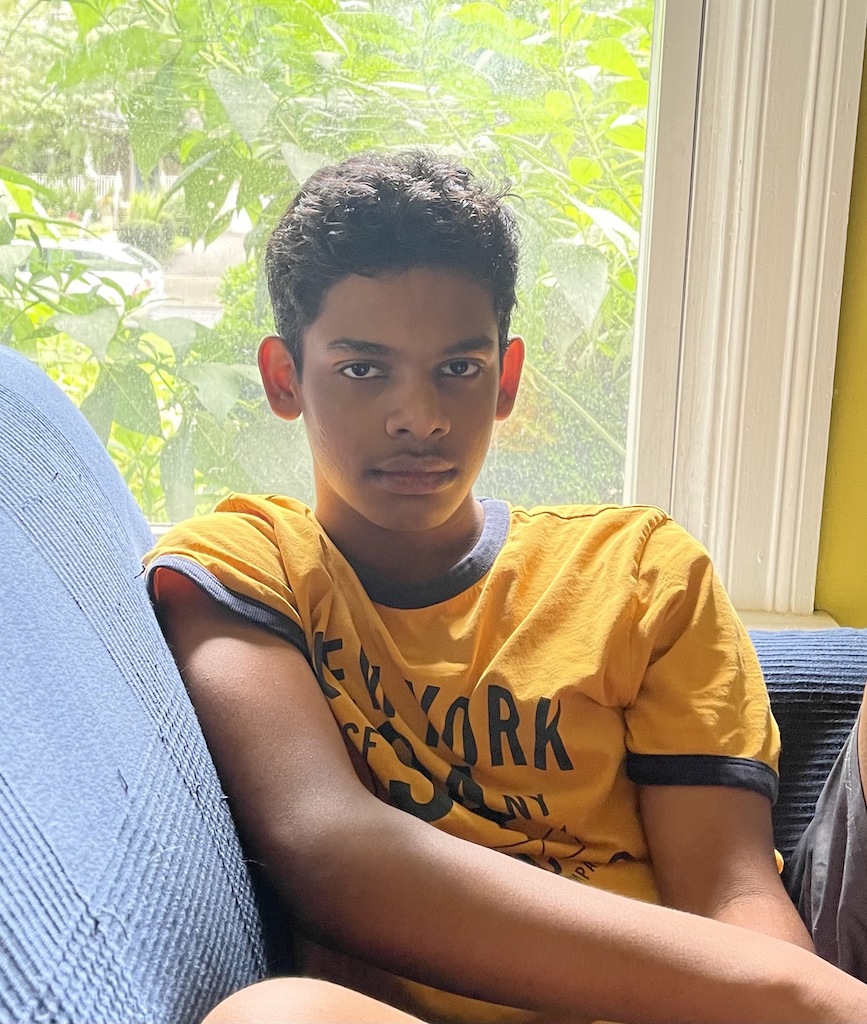

WASHINGTON – In late June, the body of 15-year-old Jay Thirunarayanapuram, a student and artist at Albert Einstein High School in Montgomery County, Maryland, was discovered near the Rhode Island Avenue-Brentwood Metro Station.

Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority investigators informed his parents that he fell from a moving train while filming himself attempting a dangerous activity known as subway surfing.

Named for a popular video game, subway surfing is the act of riding on top or in between rapid transit cars. The dangerous practice is part of a more significant social media trend known as “urban exploration” or #urbex.

On sites like Instagram or TikTok, users document themselves exploring abandoned properties and off-limits areas such as roofs and subways. The urban exploration trend first appeared online in 2007 and grew into a loose-knit community of people.

Thirunarayanapuram was one of them.

“He would like to use Instagram all the time, and it is through Instagram that he actually started following the dangerous trend of urban exploration which eventually ended in so much tragedy for us and for him,” Jay’s mother, Vaishali Honawar told Capital News Service in a telephone interview.

“Initially, he joined a site where people posted going to elicit abandoned buildings. Ultimately, he kind of graduated from all that into train surfing,” Jay’s father, Desikan Thirunarayanapuram, told CNS.

Young people are particularly susceptible to dangerous internet trends, according to an advisory report issued in May by U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy. The report warned that “extreme, inappropriate, and harmful content” is widely accessible to children and teens and that repeated exposure to this content can normalize risky behavior.

Both TikTok and Meta’s terms of service do not allow showing or promoting dangerous activities such as urban exploration, but a cursory search on TikTok and Instagram shows thousands of posts related to urban exploring.

After his death, Honawar and Thirunarayanapuram gained access to Jay’s Instagram account and discovered that their son was active in the urban exploration community.

“When he posted his train surfing photos, he would get more likes than he normally did. So I think that certainly was a rush of people liking his scary adventures,” his mother said.

Jay’s parents also discovered that their son was in constant contact with other young people, some as far away as New York City, discussing and encouraging urban exploration and subway surfing.

“They would say to him, ‘You’re a legend.’ And gave him these great compliments. So there’s that sort of validation, a lot of it coming from the social media community,” his mother said.

In exchanges with fellow urban explorers, his parents discovered, their son and his contacts knew the risks they were taking. Some had tragically lost their lives during such activities.

However, the prevailing sentiment among the risk-takers was that the thrill was worth the danger, the parents said. In the event of a death, the urban exploring group believed it was to honor the memory of a person by continuing the exploration journey, the parents added.

Unfortunately for Jay, his journey ended with his death. His parents, of course, are heartbroken.

For them, Jay’s memory lives on in the artwork he created, which hangs in their Silver Spring home, and in the people he touched, such as the teachers at his school.

“He would stay after school and help them in their classrooms putting things away, he would chat with them,” Honawar said.

Jay’s parents said they had no idea their son was riding on top of trains and wanted to bring awareness to other parents about the dangers exposed to their children on social media. Their efforts have reached the halls of Congress.

Rep. Jamie Raskin, D-Maryland, called on Meta and TikTok to be more proactive in enforcing their guidelines on promoting and showing dangerous activities.

“Ultimately, the government will have to act to deal with this if the social media companies do not, but they’ve got the power right now, as well as the obligation to act,” Raskin told CNS.

WMATA has recorded five incidents of subway surfing on roofs of cars, with one resulting in Jay’s death and two resulting in injuries.

The tally does not include incidents of people riding between cars, which is extremely dangerous, and activity under the urban exploration-related hashtags on TikTok shows young people regularly riding between cars.

This year, incidents of subway surfing have been reported in Philadelphia, Chicago, Boston and New York City, where four young people died from injuries suffered while riding on top of subway cars. There were just five subway surfing deaths in New York City in the previous four years.

Raskin also sent a letter on Sept. 8 to WMATA urging additional steps to prevent urban exploration and to alert the community to the dangers of such activities with more significant public awareness efforts.

“I am fearful that incidents of people riding on tops of Metro trains may be underreported,” the congressman said in the letter.

WMATA said in a statement to CNS that it shares concerns with Raskin and has been working with New York City Transit, where subway surfing is more common, as well as safety advocate groups, to discourage the trend.

“While Metro has fortunately not seen many of these incidents, we strongly condemn any form of this dangerous behavior,” WMATA said.

However, for Jay’s parents, his interactions with other young people participating in urban exploration indicates it is very much an issue in the Washington region.

“It is absolutely present in the DC area. There are lots of people doing it,” Jay’s mother said.

Honawar and Thirunarayanapuram are continuing their efforts to bring attention to subway surfing so that their tragedy doesn’t impact another family.

“I really hope Metro will be a good member of the community and do something to stop people riding on trains,” Jay’s mother said.

You must be logged in to post a comment.