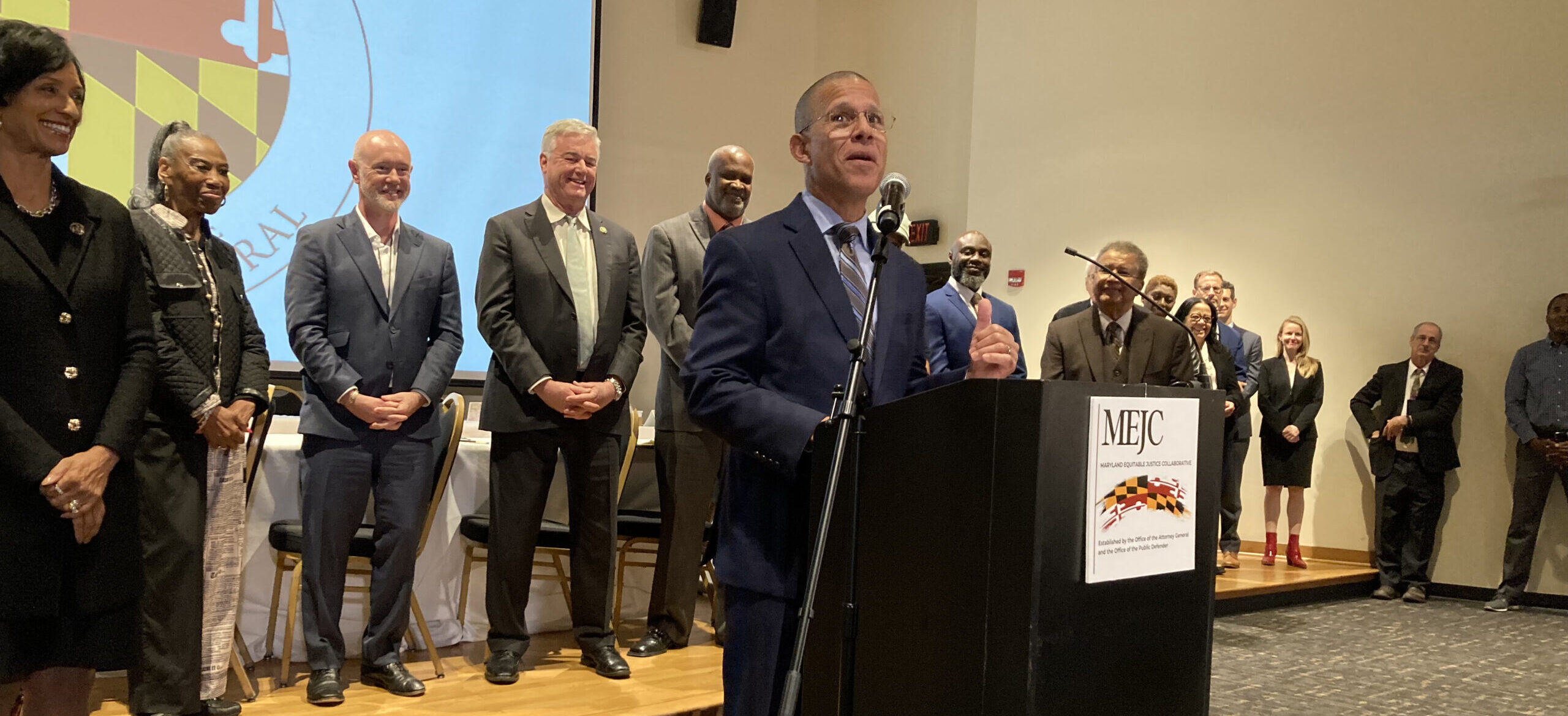

The state’s top prosecutor and defense attorney united Wednesday behind an effort to end inequities in incarceration – which Attorney General Anthony Brown described as among “the worst in the United States of America” – with a partnership including state agencies, law enforcement and justice reform advocates.

Representatives from over 40 such agencies and groups attended the launch of the Maryland Equitable Justice Collaborative at Bowie State University, kicking off a multi-year process that officials said will include legislative and funding recommendations for the coming General Assembly session.

Brown and Public Defender Natasha Dartigue underlined the disproportionate frequency and intensity with which the court and legal systems impact Black Maryland residents.

While 30 percent of Maryland’s population is Black, the state’s prison population is 71 percent Black, Brown said. Nearly eight in 10 Marylanders serving sentences over 10 years in prison are Black men, and 41 percent of these Black men entered prison as children or young adults, according to Dartigue.

“The overincarceration of Black men and women in Maryland is a crisis,” Brown told members of the collaborative.

“This is not only a national problem, it is a cancer that infects Maryland,” Dartigue said.

The collaborative’s committees, which will focus on topics such as economic and workforce development, behavioral health and reform of the youth legal system, will meet regularly in November and December and make preliminary legislative recommendations in January ahead of the 2024 legislative session. Then the collaborative will hold quarterly meetings.

The collaborative will examine biases and challenges at points of entry to the criminal justice system, recidivism and reentry, Brown said.

Brown emphasized, though, that the collaborative’s work goes beyond legislation.

“It’s going to come in a combination of recommended legislation and budgets, realignment of existing resources, stronger collaborations between government and private entities, education and practices in organizations, whether it’s police or whether it’s our schools,” Brown said.

The launch included some formerly incarcerated people working in criminal justice reform.

Earl Young, who spent almost 35 years in Maryland correctional institutions on murder charges and now works with at-risk youth at New Vision Youth Services in Baltimore City schools, called for mentoring and behavioral health services for youth and families, the establishment of effective alternatives to incarceration and rehabilitation for incarcerated individuals as soon as they enter correctional facilities.

“My sincere hope is that we can find ways to reduce incarceration and make our communities safer at the same time,” Young said.

Gwen Levi said that if she had received more effective rehabilitative services, she might have avoided being taken back to jail. Levi, a Baltimore grandmother who served 16 years for dealing heroin, was returned to custody after failing to answer phone calls from officials while attending a computer class.

“Unless we start at the beginning and make sure people are rehabilitated from day one that they go in, unless we give programs that are meaningful for their release … we can continue to see those people returning to prison,” Levi said.

Nicole Hanson-Mundell, the executive director of Out For Justice, said that as a formerly incarcerated woman, she was heartened by the diversity of the collaborative.

“In other spaces like this, formerly incarcerated women are not elevated,” she said. “At this current table alone … (there were) at least three formerly incarcerated women. I have never seen that happen in government agency collaborations.”

The collaborative will host a public forum on Nov. 6 at the Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Maryland African American History and Culture in Baltimore.