LEXINGTON, Miss. — A winter sun is setting over the brown, patchy field where Ronald Redmond’s kids have been playing football since they were 5. Trash is piled under the stands, the goalposts are rusting and the fence is ripped. But Redmond knows what kids who played on this field have gone on to achieve: high school stardom, college scholarships and even NFL glory.

“Stay on that football field,” Redmond recalls telling his 11-year-old son, R.J., a center and linebacker on the Lexington Colts youth football team. “You can go somewhere with that. … If you dedicate yourself to this football and your education, then you can go wherever you want.”

Tackle football is among the only recreational activities available to kids in Lexington and surrounding Holmes County, the second-poorest county in the nation’s poorest state. There are no swimming pools, no tennis courts, no soccer fields, no YMCAs.

“The opportunity for kids is at a bare minimum,” Redmond said.

Parents have good reason to believe in what football offers. According to an analysis by The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and the Howard Center for Investigative Journalism at the University of Maryland, three players on 2023 Power Five college football rosters were from Lexington, where the population is 1,154.

Put another way: One out of every 385 people from this majority-Black country town in central Mississippi played for an elite college program. It’s the best per capita rate of any town with at least 250 people in the state — and among the top rates in the nation.

As safety concerns prompt a debate over youth football, there are many reasons the sport endures in Lexington. At a minimum, football is a structured activity that teaches discipline, gives kids something to do and keeps them out of trouble. At best, it’s a path to college, a chance at a better life and a way out.

The odds of making it are long and the health risks are real, but in Lexington, many people take their chances with football.

“Football is a highlight of this community,” said Paul Reeves, whose family oversees the Lexington Colts, “because for a lot of us, that’s all we have.”

‘We want to give hope’

Willie Reeves was a pastor who knew that without structured activity, kids in his hometown could get drawn into a life of crime and violence. So in 1999, he started the Lexington Colts, hoping football would steer kids in a positive direction.

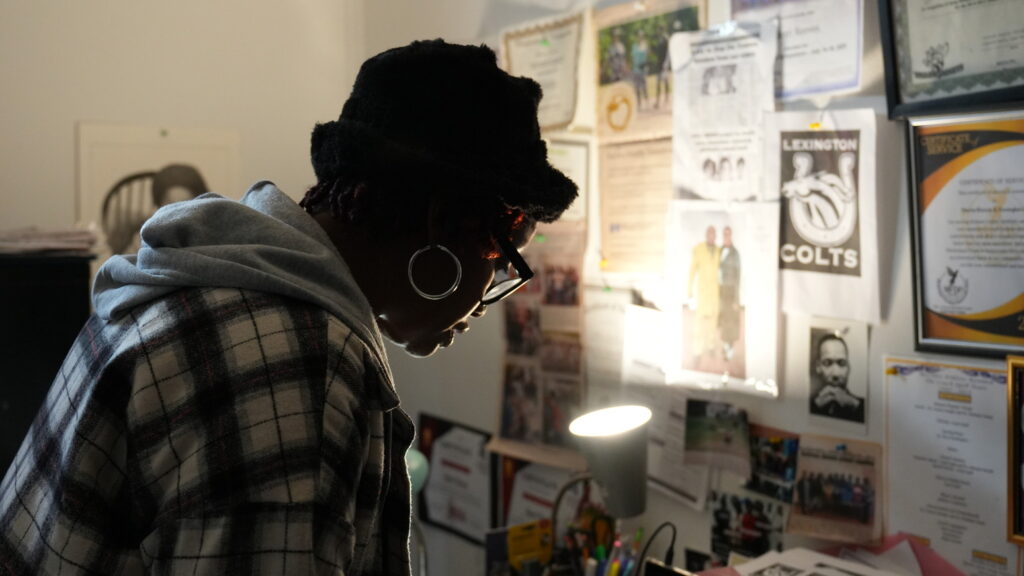

Since Willie Reeves’ death in 2017, the Colts have continued under the stewardship of his wife, Sherri, and their sons, Peter and Paul. Last year, with a strained budget and with no financial support from the city, the Colts enrolled nearly 40 kids between the ages of 5 and 12. The program has also organized clothing drives and food programs for the county, where the median household income is less than $29,000 a year.

“We want to give hope to the kids in our area,” said Paul Reeves, the Colts’ defensive coordinator. “Their talent can get wasted if they get involved with the wrong type of activities. And even worse, they can lose their lives at a young age.”

In a town where 76% of residents are African American, every child who played last season for the Colts was Black. Only two white children have signed up in the program’s 25 years.

“There’s really very little intermingling socially among the kids that are Black and white in this community,” Sherri Reeves said. “And we got firsthand of that.”

It’s not just football. There are signs of a racial divide throughout Lexington, where a Confederate monument looms over the town square, the police department is under federal investigation for civil rights violations and the schools are segregated.

At S.V. Marshall Middle School, a public school where R.J. Redmond is a sixth-grader, Black students number 345, with four white students and one Native American/Alaska Native. R.J.’s brothers, Mason, 7, and Kingston, 5, attend William Dean Jr. Elementary, where 97% of students are Black.

Meanwhile, white children make up 82% of the enrollment at Central Holmes Christian School, a K-12 private school located on Robert E. Lee Drive, which segregationists established to circumvent integration mandates.

The chance for a scholarship

Parents are drawn to the Colts in part because they hear about the program’s success stories — people like Corey Ellington, a former Colt who is now a safety at Mississippi State University. Or D.J. Montgomery, an NFL wide receiver. Or Terrance Hibbler, one of the top high school players in the state.

Hibbler received at least 18 college scholarship offers before deciding he would join Ellington next season at Mississippi State in Starkville, about 100 miles from home.

The possibilities are what convinced Redmond to enroll his sons in youth football.

“I just paid attention to that,” he said. “I learned that the earlier they get into it, the better they’ll be on the field. So I just couldn’t wait for the opportunity to present itself.”

Marcus Rogers, the head football coach at Holmes County Central High School in Lexington, attends youth football games — to support the team but also “to see what the future may hold.”

Rogers has made it his mission to help kids at Holmes County Central get into college. He estimates that in six seasons, 60 of his players have earned scholarships to colleges across the country, from the University of South Alabama to New Mexico State University.

Even legendary former University of Alabama coach Nick Saban made a handful of recruiting trips to Lexington. “If I got a thoroughbred, I know how to market him,” Rogers said.

For people in Holmes County, he added, football “gives them something to be positive about. It gives them something to brag about.”

Powerful obstacles

Cardell Wright, president of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, a local civil rights organization, said for kids in Holmes County who don’t pursue sports, the options are limited. “Outside of that, then you either go into academics,” he said, “or, you don’t do anything at all.”

Local colleges, including Jackson State University, Mississippi State University and Holmes Community College, offer academic scholarships to high school students who achieve minimum ACT scores. But according to the Mississippi Department of Education, just 20% of students at Holmes County Central met ACT benchmarks last year for college and career readiness, compared to 49% statewide.

The numbers reflect broader concerns with the county’s public schools, which were failing and taken over by the state in 2021. In their first year of college, 2020 graduates of Holmes County Central had lower GPAs than the state average and were more likely to require remedial instruction, the educational data shows. Four in 10 were no longer enrolled in college after one year.

“Whether you’ve got sports or not, it’s a challenge for kids leaving places like Holmes County, moving into life because there’s so many things they have to overcome,” said Rep. Bryant Clark, who represents Holmes County in the Mississippi legislature.

They’re the kind of obstacles that reinforce the community’s commitment to football. Clark, who serves on the board of the Lexington Colts, said youth football isn’t just about setting up a few kids for stardom. It’s about opening doors.

“Football and sports afford them opportunities to be able to go to college [and] get a free education,” Clark said. “And whether they go further out after college in football is one thing, but the sky’s the limit as far as being able to get out of college, have a degree and be able to be a productive citizen.”

Wright, the civil rights leader, agreed football offers many benefits as a galvanizing force for the community and a path to a better life. But like many others, he wishes there was more. “The thing that we’re trying to do in this area is present the kids with more options,” Wright said, “because everybody is not going to be basketball and football players.”

Last year, the county received some good news: Holmes County Central earned a B grade on the state’s annual report card, an achievement it marks on a sign outside the school. “It really represented that our kids are not hopeless,” Wright said. He hopes it persuades officials to invest in kids in Holmes County and expand opportunities in the arts and sports.

In the meantime, there’s football.

“That can be you out there on that field,” Redmond remembers telling his sons as they watched an NFL game. “It all boils down to what you want. If you want it, you can get it.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.