On a Friday night in July 2022, Jose Carlos Zamora was on the phone with his father, renowned investigative journalist and publisher José Rubén Zamora.

Jose Carlos wanted to make sure his wife and kids had settled in at his parents’ house in Guatemala City, where they had flown that day to spend the last week of their summer vacation.

Suddenly, he heard his mother screaming in the background: “They are coming in,” she yelled. “There are people on the roof!”

Jose Carlos knew instantly what was happening. He’d experienced this before in 2003, when armed men entered their home and held the family hostage.

He hung up, called his wife and told her to hide the kids in the closet; police were about to break in. Minutes later his wife sent him photos of armed men and women in Special Police Forces uniforms inside the home.

“I learned about it in real time,” he told Capital News Service in a Zoom interview. “They took their phones away, but I got the pictures and I tweeted them immediately. It became this big international news, which they weren’t expecting at all.”

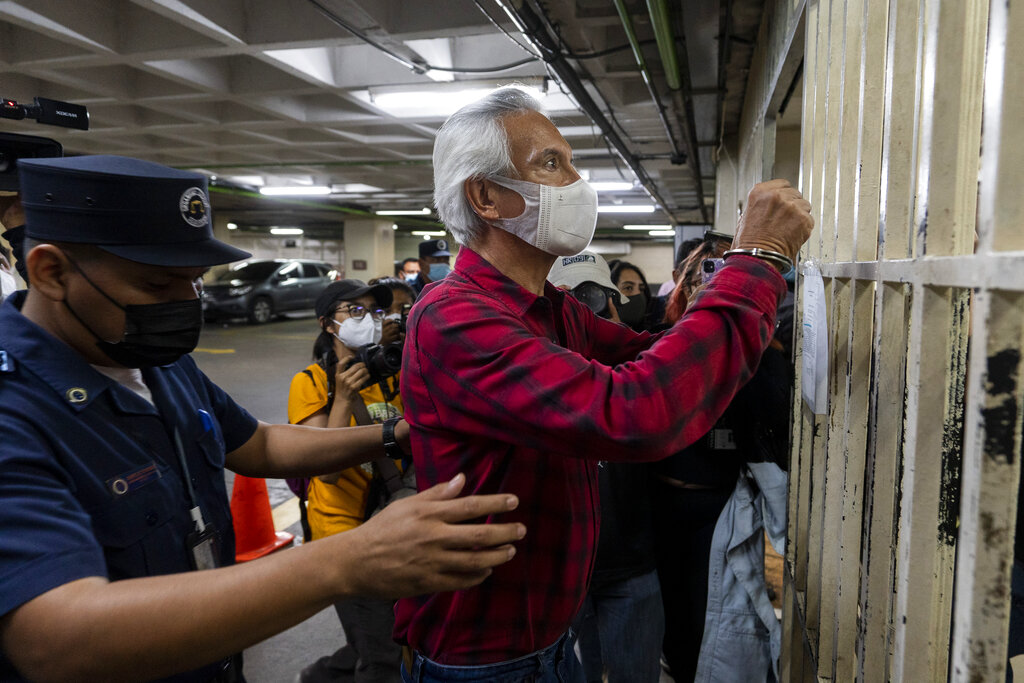

The officers held the family for six hours before arresting his father, Jose Carlos said. They accused his father of money laundering, blackmail and influence peddling.

IMPRISONED

Nearly a year after his arrest, Zamora, 67, was convicted of money laundering related to a $30,000 deposit that he said was an anonymous donation to El Periódico, the daily investigative newspaper he published. He’s been in prison ever since.

Press freedom groups around the world say officials are misapplying the law to silence Zamora and send a warning to other journalists in Guatemala.

“They have decided to not only punish him for his history of denouncing corruption, but also to turn him into a warning for journalists of what can happen to those who become too annoying,” said then-President-elect Bernardo Arévalo, speaking at the Central American Journalism Forum in the fall.

A Guatemalan appeals court overturned Zamora’s sentence last October, and he’s been waiting in prison for his new trial, which is scheduled to begin February 21.

In response to questions by CNS, Nestor Torres, a spokesman for the Embassy of Guatemala in Washington, said in an email that the executive branch has no influence over judicial decisions.

“The Guatemalan Government reiterates its full respect for the rule of law, the independence of powers, democratic principles, and the importance of alternation of power,” Torres wrote.

DEDICATED TO TOUGH PROBES

El Periódico has been a pillar of investigative journalism in the country since Zamora founded it in 1996.

Edgar Gutierrez, a former columnist for El Periódico who lives in exile in Mexico, credits Zamora with modernizing Guatemalan journalism and training the next generation of reporters.

“There is a type of journalism in Guatemala before and after José Rubén,” Gutierrez said.

Zamora led the paper through coverage of eight different presidents and hundreds of legal actions filed against him and El Periódico.

He also faced physical violence and intimidation because of his reporting. In 2003, he and his family were held hostage by armed men for more than two hours. Five years later, Zamora was kidnapped, beaten and left on the side of the road.

“Pretty much anything that repressive regimes do to attack journalists…they have done to his team, to him and to his family,” his son said.

In 2021, the newspaper published two explosive articles, one about allegations that Russian mining companies bribed former President Alejandro Giammattei and the second describing the administration’s alleged illegal dealings to obtain COVID-19 vaccines.

“Put[ting] him in jail, it was like a trophy for all these corruption crime organizations in Guatemala,” said Cindy Espina, a former political reporter at El Periódico.

Zamora has become an international symbol of the free press over the course of his career. In November he was awarded the Press Freedom Prize for Independence from Reporters Without Borders.

In May, mounting financial pressure and legal investigations forced El Periódico to shut down after 27 years of operation.

But Zamora continues to write from prison, sending columns to his son, who publishes them on Medium.

A DECADE OF POLITICAL UNREST

Guatemala has struggled to regain political stability since the end of the 36-year civil war in 1996, which left 200,000 people dead, including many indigenous Mayans targeted by government militias.

Guatemalans saw progress for the first time in decades when the country’s U.N.-backed anti-corruption office, CICIG, ramped up investigations into government officials and business executives. Its investigations led President Otto Perez Molinas to resign in 2015.

However, in 2019 President Jimmy Morales shut down the office after it opened investigations into him and his family.

At least 86 journalists, prosecutors, judges and others who fight corruption and promote human rights have been threatened or targeted with legal action, according to digital media outlet Agencia Ocote. Many fled the country and are living in the United States and Mexico.

Those who remain take added precautions. Jody García, a Guatemalan journalist for Plaza Pública, said she often sleeps at a friend’s house or leaves the city after she publishes something she knows government officials won’t like.

“I have seen a lot of colleagues just leaving the country, because they are threatened to be detained,” García said. “Sometimes I wonder, am I going to be the next one?”

SOLITARY CONFINEMENT

Often called the “VIP prison,” Mariscal Zavala is home to convicted politicians and others, including former President Molina. They are able to come and go freely while serving their sentences, even reportedly running businesses and organized crime rings from apartment-style cells.

Zamora, however, is not in a VIP cell. He’s imprisoned in a 9-by-9-foot room in the military barracks-turned-prison on the edge of Guatemala City, his son said. All he has are books, a notebook and a pen in his cell.

He’s spent 23 hours a day in solitary confinement for the majority of his time in prison. According to recent reporting by Le Monde and the Columbia Journalism Review last month, he declined an opportunity to move to the VIP section of the prison, requesting better working conditions for the guards instead.

Reporters Without Borders’ Latin America Bureau Director Arturo Romeo visited Zamora earlier this month, noting some improvements have been made since Arévalo took office. After a year and a half in prison, lights and a heater have been added to his cell.

His son says Zamora has been subject to harassment while in prison. Hammering on the roof and surprise raids on his cell in the middle of the night with dogs often keep him awake ahead of important court dates. “A lot of it is psychological warfare,” he said.

Though he is allowed visitors, Zamora’s family fled to the United States after his arrest for their own protection.

A NEW PRESIDENT

In a surprise upset this summer, Guatemalans elected leftist anti-corruption candidate Arévalo.

Election observers determined the election was free and fair. However, government officials,

including the attorney general, launched investigations into Arévalo which he called a “slow-motion coup designed to keep him out of office.

These actions prompted international outcry and led to months of protests in Guatemala and abroad calling for the attorney general and other officials to resign.

Arévalo took office on Jan. 15, an inauguration many feared would not take place after months

of attempts by Attorney General Consuelo Porras and other officials to prevent him from

becoming president.

Zamora’s family hopes he will get a fair trial and be able to present evidence of his innocence under the new administration.

“He is in good spirits and waiting with hope for whatever comes next,” his son said in an email. “If the retrial is with impartial judges that rule by the law, we all know he will be absolved.”