WASHINGTON – Wildfires are a growing threat to every state and fire officials are asking the federal government to step in to help.

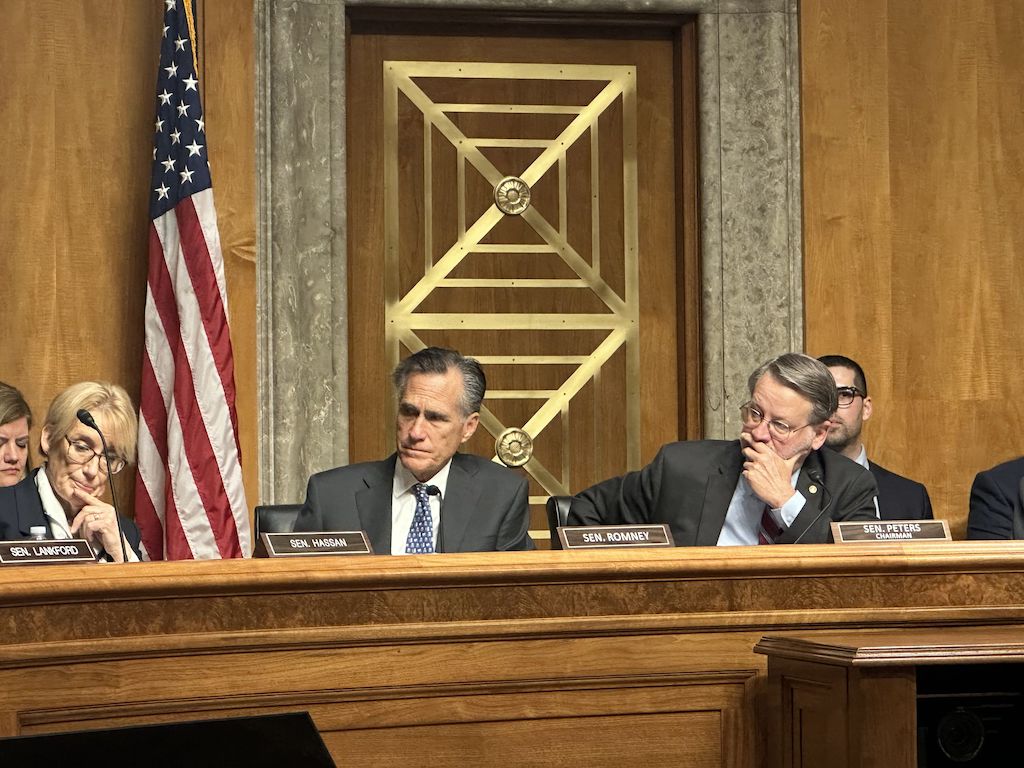

Fire agencies across the country need more support and less governmental red tape to fight these conflagrations effectively, officials said at a Thursday hearing of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.

As climate change increases the chances and spread of wildfires, the impacts of wildfires are being felt in nearly every state.

“The effects of these fires aren’t only physical danger and property damage, they also bring a host of health risks in our communities in locations hundreds of miles from fire,” Sen. Gary Peters, D-Michigan, said.

Last June, the East Coast was blanketed by thick, brown smoke from Canadian wildfires. Many major metro areas, including New York City and Washington, broke poor air quality records during the worst of the smoke.

In Maryland, last year was the worst in a decade for wildfires, according to data from the Maryland Forest Service.

While fire season is typically thought of as late spring through fall, David Fogerson, Nevada’s chief of the Division of Emergency Management and Office of Homeland Security, said this is no longer the case.

“We no longer have a fire season, but rather a fire year,” he told senators.

The Wildland Fire Mitigation and Management Commission, created in 2021 by the bipartisan infrastructure law, made 148 recommendations to improve how federal agencies respond to wildfires.

The recommendations centered on the need for agency collaboration, expanding firefighting staff and implementing proactive fire prevention techniques.

Many problems surrounding how the United States handles fire emergencies come from the lack of collaboration among FEMA, the Forest Service and other federal agencies, the witnesses emphasized.

Wildfires need to be treated like hurricanes, Fogerson, a member of the commission, said in an interview with Capital News Service.

As a hurricane approaches, federal, state, local and tribal government agencies all work together to coordinate a response. The same is not the case for wildfires, he said.

When a wildfire ignites, the responsibility falls on whatever agency owns the land. That agency is responsible for coordinating any collaboration to put out the fire, evacuate the area and set up recovery efforts.

Coordinated action against wildfires only starts after a fire crosses property lines, Fogerson said.

“It’s just a mind shift,” he said. “Instead of relying upon the fire district that owns the land to be responsible for it, all the community treats it like a disaster and takes care of that.”

Some federal agencies have struggled to adapt to the changing patterns of fires and striking the balance between environmental protection and fire mitigation, other witnesses said.

To prevent major fires, the Forest Service and local fire department perform prescribed burns. While these planned fires are good to remove excessive combustible materials, they become difficult when it comes to smoke regulations, said Christopher Currie, director of homeland security and justice at the Government Accountability Office, the nonpartisan auditing arm of the Congress.

“As you can imagine, EPA and the Forest Service have very different priorities as it pertains to wildfire smoke,” Currie said.

The current federal assistance system also struggles to help people who lost their homes due to fires, as the risk for fires in more populated areas has increased in recent years, Currie said.

It often takes longer for affected people to rebuild their homes after fires compared to other natural disasters, Currie said. Victims of fires have to manage multiple complicated federal programs that take too much time to navigate, he said.

To improve interagency collaboration and boost the number of firefighters, some officials said, there should be equal, better pay and benefits for all fire-fighting agencies.

Utah recently increased pay for the state’s wildland firefighters, making the pay comparable to federal firefighters. Jamie Barnes, the director of Forestry, Fire and State Lands for the Utah Department of Natural Resources, said this compensation was important.

“When a fire happens, it knows no boundary,” Barnes said. “We should all be making an amount that is similar so that there’s no difference in what you’re doing out there and receiving our resources.”

There is a shortage of both wildland firefighters and local structural firefighters, according to U.S. Fire Administrator Lori Moore-Merrell.

The Biden administration increased pay for federal firefighters in 2021 to $15 per hour. On top of that were temporary pay increases through the bipartisan infrastructure law.

Congress extended temporary pay increases for federal wildland firefighters in a supplemental funding bill this month. The Forest Service is asking Congress to develop a permanent pay solution for wildland firefighters, according to an agency statement in January.

When federal firefighters are not sent quickly or fully staffed, local firefighters are left as the nation’s year-round fighting force, Fogerson said.

“We’ve got to get better about having a federal wildland firefighting force that’s adequately trained, resourced, and paid, ” he said.