WASHINGTON – To better understand the ocean surface, NASA scientists went to the stars.

The Plankton, Aerosol, Cloud, ocean Ecosystem (PACE) satellite launched into orbit on Feb. 8 on a quest to better understand the microscopic content of Earth’s atmosphere and oceans.

“This mission is really the search for the invisible,” NASA project scientist Jeremy Werdell told Capital News Service.

Two Maryland teams – from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County- and a team from the Netherlands Institute for Space Research and Airbus Netherlands B.V., each worked on one of the three instruments on the satellite.

Scientists can use PACE’s data, which was first released on April 11, for both short-term monitoring and long-term climate change analysis, according to Werdell. PACE is set to send data back to Earth 12 to 15 times every day.

The satellite, which is around the size of a minivan, is designed to orbit the Earth for at least three years, but Werdell said the mission might last longer.

The Ocean Color Instrument (OCI), a project of the Goddard team, will help researchers identify the species of phytoplankton in the oceans by looking at the color of the water across ultraviolet, visible and near-infrared light.

Phytoplankton are a diverse range of plant-like microscopic algae living mostly on the surface of the ocean, according to the project website. While many species of phytoplankton are harmless and are key photosynthesizers, others create toxins harmful to humans and marine life.

PACE data could help inform water quality managers, as well as the fishing and recreation industries, about the type of phytoplankton in their regions in a more sophisticated way than ever before, Werdell said. From previous satellites, he said, scientists were only able to tell where a community of phytoplankton was, not the type of phytoplankton.

OCI’s use extends beyond the ocean. The instrument’s color analysis can be used to track vegetation on land and atmospheric particles, according to project science lead for the mission, Amir Ibrahim.

“If you’d like to breathe and eat, OCI can help us understand,” Ibrahim said. “OCI is not only going to tell us how the food chain works (and how) the phytoplankton distribution works, but also …climate change.”

The project will give new insight into how climate change is impacting phytoplankton, and thus the rest of the planet, according to Ibrahim. Phytoplankton produce around half of the oxygen on Earth, according to the Scripps Institute of Oceanography.

To get to the ocean however, scientists must clear the light-reflecting haze between the ocean and the orbiting satellite.

The two other instruments – the HARP2 and SPEXone – are polarimeters, which focus on light bounced off of particles. Both polarimeters, the latter from the Netherlands team, identify particles in the atmosphere.

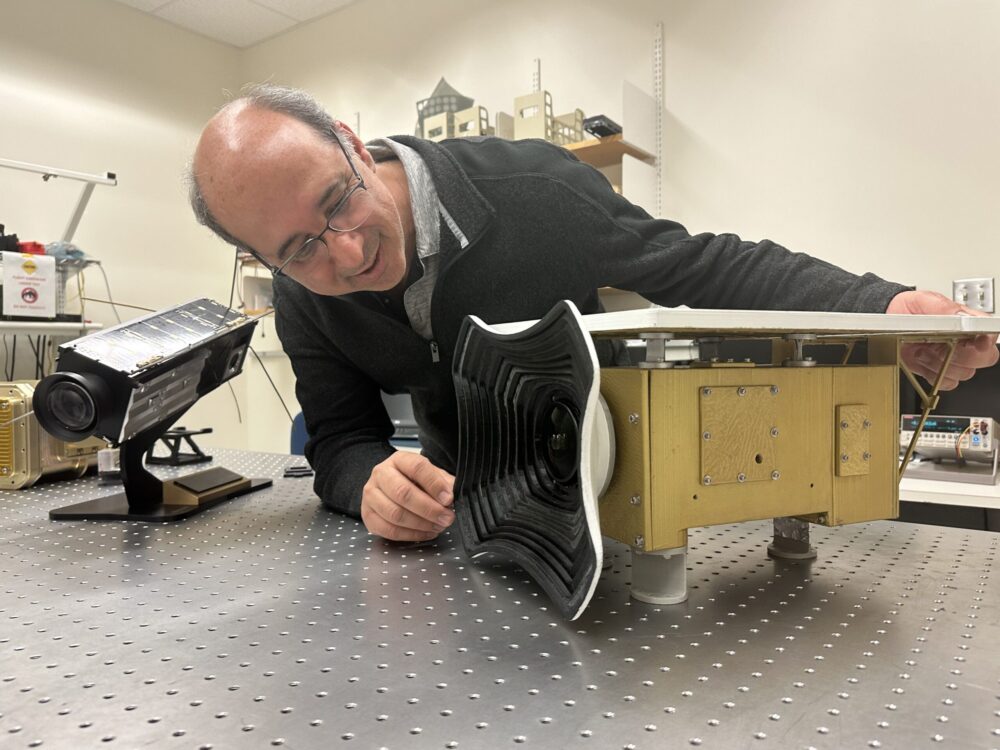

A team from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County built the HARP2, which is focused on identifying the size and content of particles in aerosols and clouds.

Vanderlei Martins, the director of the Earth Space Institute and a physics professor at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, said he hopes the HARP2 will be used by other scientists to better understand how the atmosphere interacts with the ocean and land.

“My hope is that the UMBC contributions … will help scientists around the world … have a better understanding of our planet and how it works,” Martins said. “It’s adding another piece of information to the puzzle.”

Through the HARP2, scientists can see the size and content of atmospheric droplets.

The PACE project is years in the making, Werdell said. He joined the project in 2015, just after it was officially launched, but PACE had been discussed for over 20 years.

Werdell, Martins, Ibrahim and most of the team who spent countless hours working on the satellite all anxiously awaited the launch from the Kennedy Space Center at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

Martins was standing with his team on launch day, all intensely watching every update, from the launch until they saw in a live video that their instrument was still tightly secured to the satellite’s side after the launch, and finally when the first transmission came in from space.

“It’s very emotional, every single step,” Martins said.

After launch day, the team spent months processing and inspecting the quality of the data until it was ready to be released to the public earlier this month.

Ibrahim said that the day the team finally got its hands on the first round of PACE data felt like Christmas morning.

“I was like finally, I can see the data, and I really almost teared. That data is really very special,” Ibrahim said.