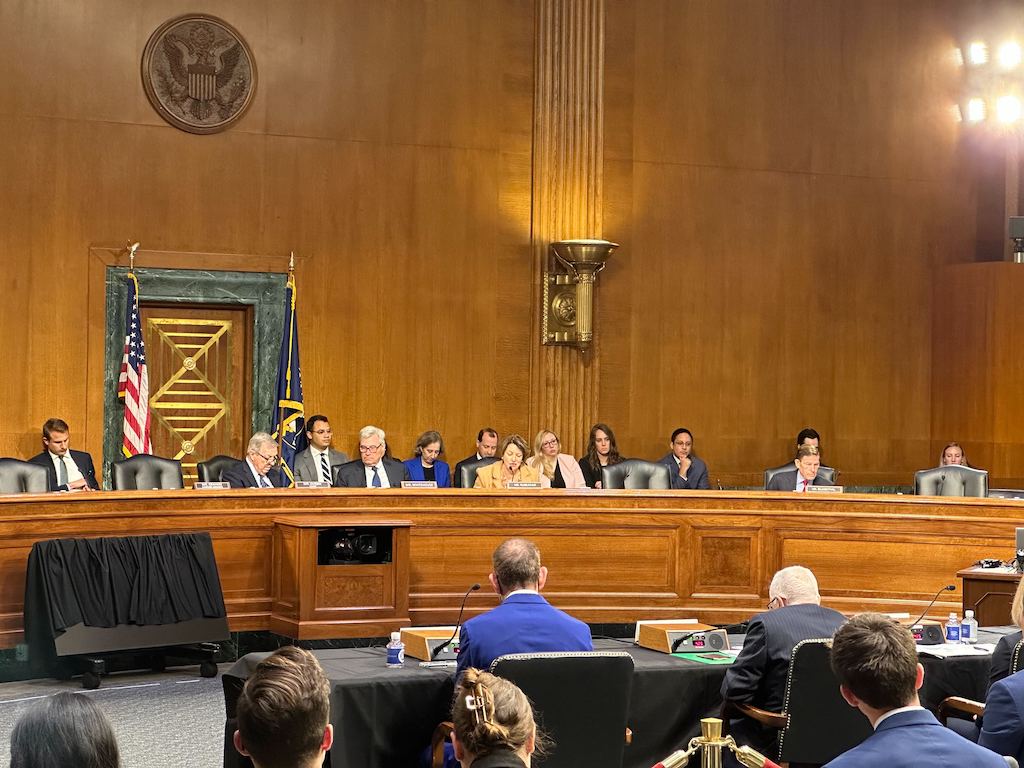

WASHINGTON – Senate Judiciary Committee members Tuesday quarreled during a hearing over the implications of the Supreme Court’s July presidential immunity decision and Democrats’ criticism of the ruling.

“Questioning the ethics of the Supreme Court is our responsibility under the Constitution, Article III,” said Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Illinois, and chairman of the panel. “I think we should continue to do that and not be questioned on our motives.”

His Republican colleagues questioned the purpose of the hearing, six weeks before the presidential election in which former President Donald Trump’s legal woes have been one of the underlying story lines.

The Supreme Court two months ago delivered a landmark decision on presidential immunity in Trump v. United States, a case that focused on Trump’s actions related to the Jan. 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol.

The court ruling divided presidential actions into three categories: core official duties which receive absolute immunity, all official duties which have at least presumptive immunity and unofficial acts which have no immunity from criminal prosecution.

Democrats attacked the decision, saying it could permit future presidents to be reckless without the underlying fear of criminal prosecution. Republicans countered that the decision could prevent politically-motivated revenge for a president’s actions in office.

Durbin noted that when Chief Justice John Roberts testified at his confirmation hearing nearly two decades ago, he said: “No man is above the law – not the president and not the Congress.”

But the immunity decision Roberts penned was “a game-changing act of judicial fiat that puts all future presidents above the law, protecting them from criminal prosecution for abusing the authority given them for personal or political gain,” Durbin said.

Republican senators and their two witnesses repeatedly characterized the immunity opinion as unremarkable and the hearing as a politically motivated attack on the conservative-dominated Supreme Court.

“This hearing is not about righting a wrong,” said South Carolina Sen. Lindsey Graham, the judiciary panel’s top Republican. “This hearing is about a continued narrative. It’s about delegitimizing a court that you don’t like.”

Republicans repeated their claims that the Democrats are weaponizing the Justice Department against Trump, the only former president to have been criminally indicted.

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, and other GOP senators listed actions by Democratic presidents as examples of instances in which the justice system could have gone after former chief executives if presidential immunity wasn’t understood, such as the internments of Japanese and Japanese Americans ordered by then-President Franklin Roosevelt during World War II.

Former Attorney General Michael Mukasey, who served under President George W. Bush, said he worried that the presidency would be whittled away without the immunity decision. Sen. Peter Welch, D-Vermont, responded: “My concern is rule law is being whittled away.”

“My concern is that constitutional freedoms are in the process of being whittled away,” Welch continued. “What’s been whittled away are the checks and balances that are the core of our constitutional system.”

Former Deputy Solicitor General Philip Allen Lacovara, who was a counsel to the special prosecutor in the Watergate investigation of President Richard Nixon, told senators that there is no historical justification for presidential immunity for official acts.

“I have no interest in attacking the court as an institution,” Lacovara said. “Rather, what I’m trying to suggest is that the court in this decision, at least, has brought criticism on itself.”

“The decision is profoundly wrong and it is profoundly dangerous,” he said, noting the majority on the court could find no precedent to buttress its ruling.

In addition to Nixon, Presidents Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton were all at some point under criminal investigation, Lacovara said. Before 2024, Lacovara told the senators, no serious lawyer or president claimed that there was immunity for crimes committed in office, including crimes committed while performing an official function.

If the July Supreme Court decision was in place before the Watergate scandal, Lacavera told Capital News Service, there would have been no need for President Gerald Ford to pardon Nixon.

“The potential abuses of official power that are made possible by the court’s ruling and the neutering of Congress’ ability to act are alarming,” said Mary McCord, executive director of Georgetown University’s Institute for Constitutional Advocacy and Protection. She served as acting assistant attorney general for national security affairs under President Barack Obama and into the early months of the Trump presidency.

Nixon directed a census of Jews in government in 1971, an action that illustrated “the corrosive and dangerous capacity of unchecked presidential power,” warned Dr. Timothy Naftali, a presidential historian who also served as the first federal director of the Richard M. Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

“…Motives do matter in the application of constitutional authority and…presidents ought to be held accountable, if appropriate, by the courts as well as the Congress for the motives that animate their decisions,” Naftali said.

Democrats in Congress have attempted to respond to the immunity decision through a series of court reform proposals and immunity-focused legislation, none of which have made significant legislative progress.