WASHINGTON — Chesapeake Bay is cleaner than it used to be but is falling short of 2025 targets for reducing pollution, federal and state officials and most of Maryland’s congressional delegation said on Wednesday.

“The short version is that it’s going in the right direction. The longer story is that we’re still behind,” Adam Ortiz, administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency’s Mid-Atlantic region, said at a Capitol Hill press conference.

The bay failed to meet the agreement’s main target, known as the total maximum daily load, which measures the total pollution in the Chesapeake Bay, Sen. Chris Van Hollen, D-Maryland, said.

“The point of the 10-year plan is to create a pollution diet to reduce the amount of phosphorous, nitrogen and other pollutants in the bay,” Van Hollen said. “That’s a measurable target. That’s how we know we’re not going to hit it this year, so we need to redouble our efforts.”

Despite missing the targets set in 2014 through 2025, Sen. Ben Cardin, D-Maryland, said he remained hopeful that the delegation can work together with experts at the EPA and other agencies to ensure the bay’s health continues to improve.

Maryland Democratic Reps. Steny Hoyer, Dutch Ruppersberger, Kweisi Mfume and Jamie Raskin joined Cardin, Van Hollen, representatives from the EPA and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

Maryland Democratic Reps. Steny Hoyer, Dutch Ruppersberger, Kweisi Mfume and Jamie Raskin joined Cardin, Van Hollen, representatives from the EPA and the Maryland Department of Natural Resources.

The University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science gave the Chesapeake Bay an overall grade of a C+ in July, the highest grade the bay has received since 2002.

“I know that nobody would be thrilled with bringing home a grade of a C+, but the fact of the matter is, it is the highest grade we’ve seen in a long time,” Van Hollen said. “We all want to do better, but I do want to stress that without the collective effort we see today, the bay would have died a long time ago.”

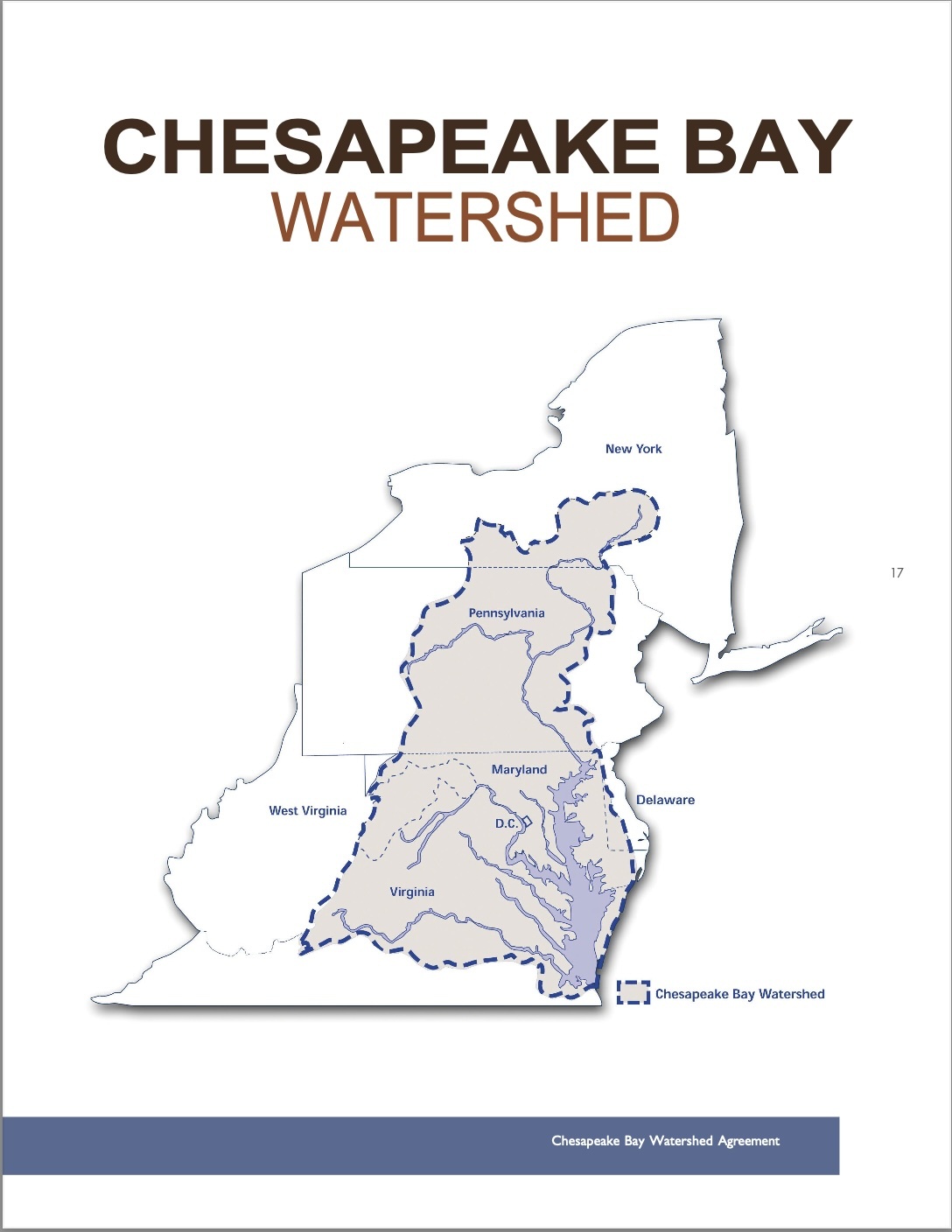

The Chesapeake Executive Council signed the Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement in 2014 and established five strategies for the restoration and protection of the bay, its tributaries and surrounding lands.

Local, state and federal governments are required to enact the plan’s management strategies and work with academic institutions, nongovernmental organizations, watershed groups and businesses and individuals, according to the 2014 agreement.

“You need cooperation between the federal government and the states, among the states, among state governments and private industry,” said Van Hollen. “There are all sorts of sources of pollution today, and so we need to make sure everybody cooperates in producing pollution reduction.”

Ortiz said that groups committed to improving the bay were in disarray when President Joe Biden’s administration began almost four years ago.

“The states were suing the federal government, and states were pointing the fingers at each other for not making…progress,” he said.

But since then, he said, the EPA has been able to bring the states together and hold them accountable.

“The Chesapeake Bay isn’t just a bay,” Cardin said. “The Chesapeake Bay has been one of the highest priorities for our Maryland congressional delegation. We’ve been focused on not only preserving but expanding our role and partnership with states, local governments and stakeholders.”

Van Hollen emphasized the importance of identifying “measurable targets” of pollution reduction for long-term success, especially as climate change concerns surrounding the bay grow.

“I think we’ll have to have a discussion about what the length of time for the next agreement should be. It may make sense to look at shorter time horizons,” the senator said. “But you have to have a measurable target to hold people down.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.