By 11 a.m., Jon Merryman had collected 45 tires, 38 bags of trash, packs of shingles, a mattress, a playpen and remnants of an accident swept under a guardrail near College Park, Maryland.

Merryman, 62, was frustrated and restless. The Nov. 6 election hadn’t gone his way. A veteran and a man of action, he turned to a lifelong passion to cope: picking up trash.

Over the following days, he cleaned up roadsides in 22 counties spanning Virginia and West Virginia.

“I call it channeling my anger,” Merryman said, tone dropping.

Physical work helps him maintain his emotional and mental health. When he returned home to Catonsville, Merryman felt more rejuvenated and ready to face what came next. For him, cleaning up litter is a way to reclaim control, one piece of trash at a time, in a world that can feel overwhelming.

“I want people to feel like one person can make a difference,” he said.

Merryman traces his passion for protecting the environment to campaigns from his childhood. Campaigns like “Smokey the Bear.” “Woodsy the Owl.” The 1970s commercial “Keep America Beautiful: The Crying Indian.”

While controversial today, the “Keep America Beautiful” ad had a simple message for 7-year-old Merryman: “People start pollution. People can stop it.” Inspired, he planned a post-Halloween mission to clean up wrappers and litter. With a full bucket, Merryman marched down to a storm drain, thinking that’s where the trash should go.

“Thank God an adult was there,” he said. The passerby explained how storm drains lead to rivers. He didn’t know it yet, but Merryman would dedicate much of his adult life to rectifying this mistake.

The makings of a soldier: from protecting nature to protecting country

Merryman’s cousins, conservationists on Maryland’s Eastern Shore, took him under their wings and ignited a passion for studying the environment. They invited him on bird banding and counting trips. Merryman remembers the sky filling with “rivers of birds” for 15 minutes at a time. Clicker in hand, he counted birds until his hand grew weary.

“You’re witnessing the miracles of being on earth when you see stuff like that,” Merryman said.

His cousins later dissuaded him from becoming a marine biologist.

“They got me geared up for this life of studying animals, then said, ‘Oh, you don’t want to do that. It’s a life of chasing grants.’”

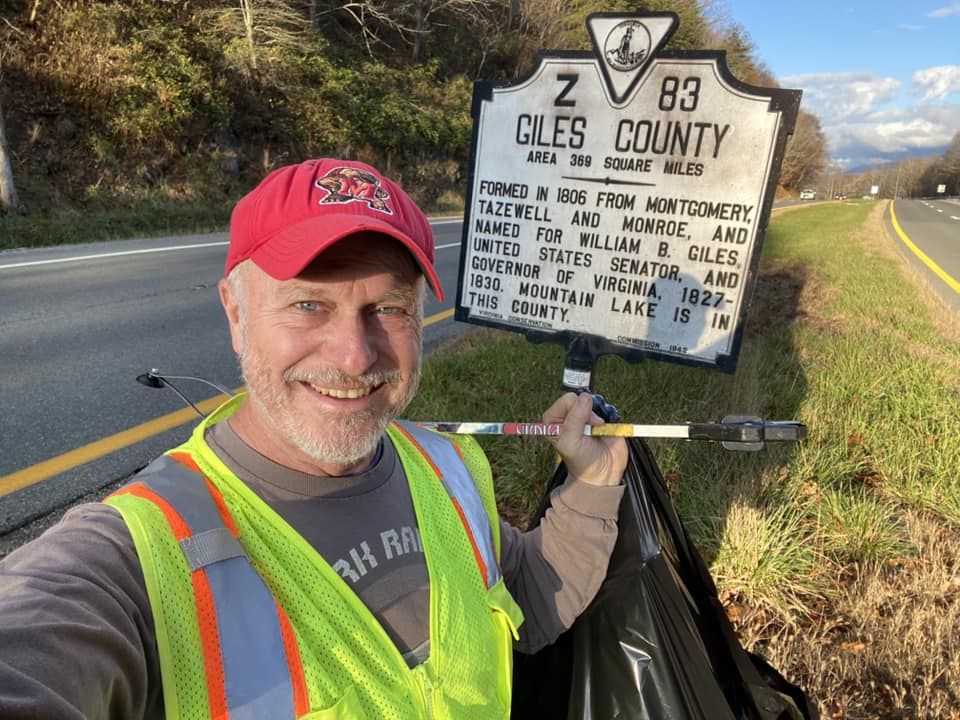

Jon Merryman embarks on another trash pickup on the side of the road in Giles County. (Photo provided by Jon Merryman).

Merryman entered the University of Delaware as a biology major. Switched to geology. Jumped to civil engineering. His GPA plummeted. He pivoted to part-time status while working for the university. Eventually, he found his footing in geography while programming educational software. Also minored in photography.

His first summer out of college, Merryman worked as a volunteer ranger at the Grand Canyon, giving talks, leading groups and picking up trash in front of the visitor center. “Funny thing is, that’s what I love to do now: pick up trash.”

The staff liked him and encouraged him to apply for a seasonal park ranger job, but then Congress slashed funding, so the job didn’t exist.

Merryman took on seasonal jobs. While working in the Everglades, he saw a billboard promoting the army’s college fund.

It offered $20K for two years of service.

“Great option,” he thought. He enlisted in the army and spent six years in the National Guard.

‘My wife puts up with a lot’

When Merryman returned to civilian life, he worked in instructional technology. “As it turns out, there’s a lot of commonality between arranging the elements of a map and arranging the elements on a computer screen,” he said.

Jon Merryman holds a song sparrow after it survives a window collision. (Photo by: Alisha Camacho/Capital News Service)

But his passion for the environment remained. One day, while working at Lockheed Martin, Merryman came across a trash-strewn creek and park. He spent five years turning it into a sustainable habitat.

His hobby of picking up trash also found its way home. “My driveway was full, I mean seriously, full of scrap metal,” he said. He sold the metal from cleanups to fund his kids’ robotics team. “The things we do,” Merryman chuckled.

Through it all, he said, it took a lot of patience from his wife, Kirsten. “The spouses that put up with it are angels, too. They are. My wife puts up with a lot.”

Turns out, so do his kids.

Litter everywhere in the middle of nowhere

A common conundrum Merryman encounters is people acknowledging a problem but not taking responsibility. “Someone else is doing the littering. It’s those people,” they think.

Merryman became determined to show that littering is everyone’s problem. During a road trip with his son to Los Angeles, an idea emerged, and they cleaned up trash in one county per state, adding two counties for Texas.

When they arrived “in the middle of nowhere” in Turkey, Texas, Merryman found “litter everywhere.” He wanted people to realize that we are all responsible for this pile of trash because of all the things we buy and the resources we use.

To illustrate the extent of trash pollution, he started placing green dots on a map of counties he’d clean up.

“I’m a map geek,” Merryman said. He had been tracking all the counties he visited for years, a hobby shared by fellow geographers. Now, he aims to pick up trash in every county for as long as possible.

Recently, he picked his daughter up from school in Ithaca, New York. As they left Ithaca and crossed over into the Chesapeake Bay watershed, an idea “dawned on me,” he said.

He’d picked up trash in counties between Ithaca and Baltimore, having done this drive many times. “I put those on the map,” Merryman said when he realized he was nearly halfway done. “I bet I could do them all” in the watershed.

He now focuses on watersheds rather than state lines. Water carries pollution across borders, so “state boundaries don’t matter as much as the watershed,” he said.

On Dec. 1, 2024, Merryman reached his goal. He picked up trash in all 206 counties in the Chesapeake Bay watershed. Bringing his total count to 524. One-sixth of all counties in the United States.

Sharkey d’Shark

On February 2, 2022, at 2:22 p.m., Merryman retired — a moment he carefully planned. “I walked out the door,” said Merryman. “I just thought it was funny.”

A few months later, Merryman found his retirement buddy, Sharkey d’ Shark, on the side of the road. The abandoned toy-turned-sidekick became a playful way to engage others in cleanups.

Sharkey has a social media presence. “It’s a lot easier to have a back-and-forth conversation with Sharkey,” Merryman said, “as opposed to writing posts and getting crickets in response.”

Merryman hopes Sharkey can help educate and inspire younger generations to partake in cleanups. For now, “about 90% of Sharky’s fans are middle-aged women,” he laughed.

Nature is innocent

When not traveling to pick up trash, Merryman volunteers with Lights Out Baltimore, searching for dead or injured birds hit by windows due to disorienting artificial lights.

“Nature, as far as I’m concerned, is all innocent,” Merryman said. Migrating birds navigate at night using the moon and stars, but lights lead them to windows. “There’s a reason it’s happening. It’s not because the bird’s stupid,” he said. The birds can’t see the glass.

Not long ago, Merryman found an old Facebook post when he first joined the group and held a bird for the first time in decades. Now, he’s active in several Facebook groups where he educates others about window strikes. Sharing photos of the dead birds tends to upset people, especially those who have already seen them.

On the one hand, Merryman speaks to newcomers who aren’t aware of this issue and spreads awareness “over and over and over again.” On the other hand, some people complain and don’t want to see the photos.

“I’m sorry if it makes you feel squeamish,” Merryman said, his tone serious. He paused. “Actually, I’m not. I’m not sorry,” he said with a wry laugh. “I hope that it will make you care about it.”

Jon Merryman prepares a label documenting the recent victim of a window strike. The survivor is placed in the brown bag until transported to the Phoenix Wildlife Center, where it will receive medical care before being released. (Photo by: Alisha Camacho/Capital News Service)

A red-bullied woodpecker did not survive a window strike near the Light St. Pavilion in Baltimore. (Photo by: Alisha Camacho/Capital News Service)

It is a difficult line to walk — getting people to care without turning them away. “I’m just not good at drawing that line personally,” he admitted.

But he is good at showing up and doing the dirty work. “I’m happy to be the grunt, the foot soldier.”

Merryman has a plan for the rest of his retirement. He is going to pick up trash in every county in the United States. Until he physically can’t anymore. Then he hopes to write a book.

So far, he’s crossed off Arizona, Vermont, New Hampshire, Maryland, Virginia, Delaware, and New Jersey while nearing the finish line in Pennsylvania and Virginia.

Maybe he won’t reach his goal. “But I’m gonna die trying.” And maybe the world will be a little cleaner, with a few more birds in it.

Jon Merryman carries a bucket filled with rescued birds in brown bags as he continues his morning shift with Lights Out Baltimore. (Photo by: Alisha Camacho/Capital News Service)

Learn more about Lights Out Baltimore: If only birds were ‘puppies’: Lights Out Baltimore tracks 3,000 window collisions since 2018

You must be logged in to post a comment.