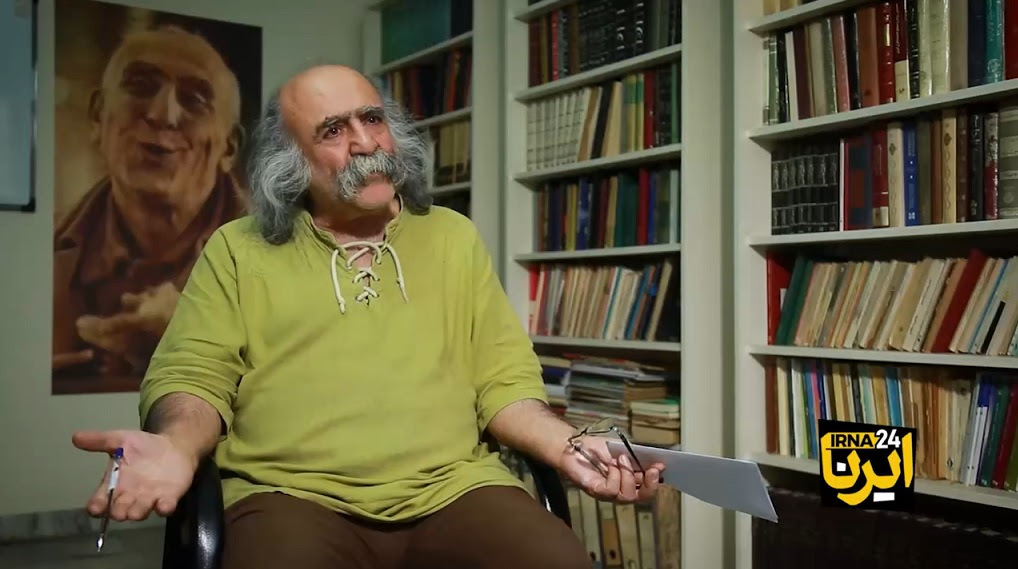

Keyvan Samimi was one of Iran’s oldest political prisoners. At 76 years old, the veteran journalist and political activist had spent more than 10 years behind bars on and off until he was released in 2023.

Samimi was first imprisoned in 1966 at age 17 and has since been arrested at least 10 times.

“The fact that he was imprisoned under the shah and in prison under the new [Islamist] regime really speaks to the way that these different regimes in Iran have all criminalized free speech,” said Alex Shams, an Iranian-American anthropologist and editor-in-chief of Ajam Media Collective, a U.S.-based diaspora platform focused on West and Central Asia. “A figure like him doesn’t only see his struggle against the government of the Islamic Republic. He sees his struggle as being against tyranny.”

Samimi’s experiences exemplify one of Iran’s greatest issues for journalists: the inability to tell a story without becoming the story.

“As a journalist, your whole point is that you shouldn’t become the news. You should be reporting the news,” said exiled Iranian reporter Kay Armin Serjoie, who spoke with Capital News Service in a phone call from Europe. “But it’s very hard to remain inside Iran, focus on the news and not somehow become involved.”

Samimi is just one of hundreds of reporters and pro-democracy advocates who have been imprisoned in Iran for what the government said was conspiring with foreign powers against national security and spreading anti-establishment propaganda.

“Anybody who’s a journalist inside Iran who isn’t 100% towing the party line, even if they’re working for state media, is suspect,” Serjoie said.

CNS’ attempts to reach Samimi in Iran were unsuccessful.

Iranian officials in Iran and at the Permanent Mission of the Islamic Republic of Iran to the United Nations did not respond to requests for comment.

Samimi was a pioneer of independent Iranian media. He is the editor-in-chief of the Iran-e Farda (Tomorrow’s Iran) magazine and the former editor-in-chief of the now-banned intellectual newspaper Nameh (Letter). His career spans decades and includes coverage of labor rights and protests, advocacy for press freedom and democracy and criticism of the government.

In 2023, Samimi was given a six-year sentence after being found guilty of “collusion and propaganda against the establishment” for an open letter he wrote from jail blaming judicial authorities for the COVID-related death of a fellow inmate during his previous incarceration months earlier.

Samimi had been arrested a day before he was due to speak at the “Dialogue to Save Iran,” a virtual conference hosted by the National Iranian American Council on April 20, 2023.

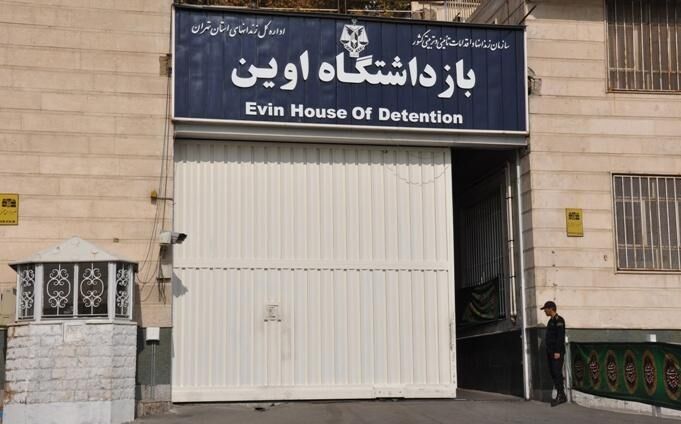

He was held in Evin Prison, a detention facility in Tehran notorious for its human rights abuses and mistreatment of political prisoners, according to the U.S. State Department’s annual 2022 human rights report.

He was released on bail on May 22, 2023, according to a social media post from his lawyer, Mostafa Nili, and has been free ever since.

Recent crackdowns on dissent

Government repression of civilian protests escalated in September 2022 after the death in custody of Mahsa Amini, 22. Morality police had arrested her for allegedly exposing more hair than the country’s compulsory hijab law permits. Her death incited a massive wave of civil unrest and nationwide demonstrations led by young Iranian women that became known as the Woman, Life, Freedom uprising.

Since the uprising began, at least 19,200 people have been arrested and over 500 protesters have been killed, the U.S.-based Human Rights Activists News Agency, a human rights monitor, reported in April 2023.

The Iranian government has often used violent tactics to stop protests since the 1979 Islamic Revolution that overthrew Iran’s last king, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, and his corrupt, U.S.-backed monarchy.

Shams said the government “has become much more sensitive to journalists’ espousing support for these movements because they’ve seen them become much stronger and more capable of challenging them.”.

On Oct. 14, Iranian authorities announced that the two reporters who broke the news of Amini’s death, Niloofar Hamedi, 32, and Elaheh Mohammadi, 37,were cleared of charges of corroborating with the U.S. government but would still serve five years in prison for spreading anti-establishment propaganda.

Government control of media

The government attempts to control media reporting about the country both inside and outside of Iran.

“If you report outside of Iran in Persian, then that means your target audience is in Iran, and the authorities do not like that,” said Kian Sharifi, an Iranian feature writer for the U.S.-funded Radio Farda.

“There are plenty of stories about how the authorities in Iran have put pressure on the families of journalists in an attempt to get them to either tone down [their reporting] or worse: to spy on their colleagues,” he said.

Samimi’s family has suffered greatly under various Iranian governments. Pahlavi’s government executed one of his brothers, Sassan . The Islamic Republic executed another, Kamran. Both were involved in leftist political movements that opposed the two regimes.

Timeline

In 2009, Samimi was arrested for his coverage of the contested Iranian presidential election. He was sentenced to six years in prison for “propaganda against the system” and “assembly and collusion [with foreign powers] against national security,” according to Iran Human Rights, a Norway-based foundation that monitors freedom issues in Iran.” The court also imposed a 15-year ban on his “political, social and cultural activities.”

During this imprisonment, he was held in solitary confinement for several months for participating in hunger strikes to protest the prison’s poor conditions.

The few photos available of Samimi show his deterioration over the years—eyes sinking into his deeply lined face; hair graying and thinning, and an overgrown, unkempt white beard accompanying the thick mustache hiding his lips.

For over a decade, media outlets reported his intensifying heart and lung conditions, liver disease, severe arthritis and stomach and knee problems. He was briefly hospitalized twice in 2013.

Samimi served three more years in prison on the same charges in 2020, a sentence that was temporarily paused for three months in 2022 due to his worsening health and risk of complications if infected with COVID-19, according to Human Rights Watch, an international research and advocacy organization.

Phone access in prison

Samimi was active on his public Telegram channel during his previous times in prison, even from his cell. But for over a year following his most recent arrest, he stopped communicating on Telegram.

Although the encrypted messaging service has been banned in Iran since 2018, over 50 million users access Telegram through Virtual Private Networks (VPN), according to the BBC.

Personal phones are not allowed in prison, but many prisoners find ways to get them anyway. A former political prisoner in Evin told CNS that importing and selling SIM cards is a “profitable business” among prisoners.

Nahid Naghsbandi, the Iran researcher at Human Rights Watch, said political prisoners have to “hide [their phones] or get some sort of agreement with the guards.”

The former inmate, who asked not to be named for safety reasons, said his ward would be searched without notice to “collect any illegal things, such as mobile phones, SIM cards, drugs and sharp objects.” The ward was often punished by losing access to the prison’s landline phones.

In July 2024, Samimi began posting again to congratulate the 60% of voters who abstained in protest during the first round of the presidential election and to endorse the reformist candidate in the second.

“A year ago, I was arrested for participating in the “Saving Iran” dialogue conference, but I believe that we should not stop making demands at any cost,” Samimi wrote in Farsi on Telegram. “Saving Iran is a process…I will spend the rest of my life fighting for the people and youth of Iran.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.