ANNAPOLIS – A bipartisan group of lawmakers is attempting to push Maryland’s Department of Health to restrict the distribution of two veterinary tranquilizers that play a growing role in the state’s overdose crisis.

The agency has thus far resisted pressure to add the tranquilizers to the state’s list of scheduled drugs – unlike neighboring Delaware and Pennsylvania, where officials have recently scheduled the more common of the two drugs. Both MDH and some drug-user outreach groups argue the state should avoid taking steps that might prompt the illicit drug market to find new, untested substitutes.

In the eyes of some Maryland Republicans, however, MDH’s reluctance is a concession to drug dealers. “Their failure to act has cost lives,” said Sen. William Folden, a Republican representing Frederick County.

Xylazine, the better-known of the two tranquilizers, has become a staple of the mid-Atlantic’s illicit drug supply. According to data from the state’s Office of Overdose Response, more than a quarter of the roughly 2,500 Marylanders who died from fatal overdoses in 2021 had xylazine in their system, compared to roughly 17 percent just a year earlier.

Law enforcement first detected the other tranquilizer, medetomidine, in a Maryland drug sample in 2022. In the last quarter of 2024, MDH testing detected medetomidine in just over 8 percent of samples collected.

Many of Maryland’s neighbors have reacted to these regional shifts by adding xylazine to their lists of scheduled substances. Scheduled drugs are subject to stricter distribution rules, creating hurdles for those diverting the drugs into the black market. Xylazine and medetomidine aren’t classified as controlled substances under federal law. Maryland law delegates that authority to schedule drugs at the state level to MDH.

MDH spokesperson Chase Cook told Capital News Service that, after reviewing the outcomes of scheduling xylazine in neighboring states, his agency determined that the restrictions could do more harm than good.

“Both Pennsylvania and Delaware scheduled xylazine through temporary orders and both are now seeing increases in opioid overdoses with medetomidine,” he said. “This follows the iron law of prohibition where, even with alcohol prohibition, more potent substitutes replace the prohibited substance in the illicit supply. Pennsylvania and Delaware are seeing this less than a year after scheduling xylazine.”

Though the proliferation of xylazine in Maryland began before the COVID-19 pandemic, this year marks the first time state lawmakers have attempted to restrict access to the drug.

Xylazine became a nearly unavoidable feature of the illicit drug supply during the pandemic, leaving drug users and healthcare providers alike scrambling to adapt. Unsuspecting users frequently lose consciousness, slumping over and losing circulation in their extremities. Frequent xylazine users often develop open sores on their limbs, increasing their risk of infection and amputation.

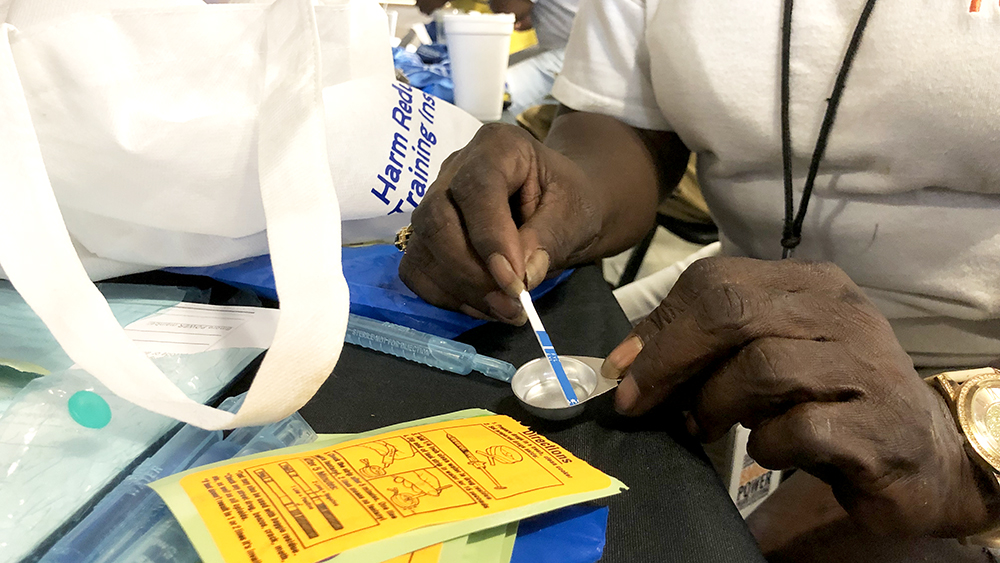

While both xylazine and medetomidine often appear in powders and counterfeit pills in combination with fentanyl, the tranquilizers — commonly known as ‘tranq’ — aren’t opioids. That means common opioid overdose-reversal drugs like naloxone can’t treat a xylazine or medetomidine overdose, although public health agencies still advise administering naloxone to people displaying overdose symptoms as a precaution.

Sarah Laurel, founder and executive director of the Philadelphia harm reduction nonprofit Savage Sisters Recovery, has more experience than most with the grim consequences of xylazine’s rise.

But Laurel is also a firm opponent of scheduling the drug.

“It incentivizes the criminal drug market to find more potent, potentially dangerous substances, and then we have to test the drug supply, find out what those substances are and what the negative consequences to users could potentially be,” she told CNS.

Like MDH, Laurel argues that the aftermath of Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro’s decision to schedule xylazine at the state level in 2023 demonstrated the risks involved in playing cat-and-mouse with new street drugs.

“Now we see the introduction of new things such as very high amounts of lidocaine and tetracaine,” she said.

Laurel says her organization now encounters anesthetics like lidocaine when testing street drug vials from Philadelphia more frequently than it encounters xylazine or fentanyl. Samples containing medetomidine are also increasingly common. Once again, her team is rushing to catch up.

But Maryland lawmakers pushing to regulate xylazine and medetomidine argue the General Assembly is morally obligated to limit access to the drugs by whatever means possible.

House Minority Whip Jesse Pippy, a Republican representing Frederick County, is the House sponsor of a bill intended to draw lawmakers’ attention to the subject. While Frederick County isn’t the epicenter of the state’s overdose crisis, the county delegation’s ties to law enforcement are a frequent source of legislative inspiration.

The bill would set civil fines for drug distributors who provide xylazine or medetomidine to customers who can’t prove that the drugs are for legitimate veterinary uses – namely as a sedative for livestock. Revenues collected from those civil penalties would be spent on the state’s overdose prevention programs.

“This is a midway step to where we can say, ‘Look, you cannot, other than for veterinary purposes, be giving this stuff out right now,’” he told fellow lawmakers. For now, he added, “there are probably a million different ways to get it out on the street legally.”

Folden, the sponsor of a parallel bill in the state Senate and an officer with the Frederick Police Department, underscored that the proposed penalties wouldn’t involve jail time. “It is important to emphasize that this bill only creates civil penalties, not criminal,” he said. “You want to make them criminal [penalties]? I’m not going to fight that.”

The proposals have the backing of the state attorney general’s office and faced no vocal opposition in committee hearings. The American Veterinary Medical Association has previously supported scheduling xylazine at the federal level, though the association’s Maryland branch did not immediately respond to inquiries about its position on the legislation before the General Assembly.

Folden and other backers maintain that they would prefer to see MDH schedule xylazine and medetomidine. So far, the agency has not testified on this year’s proposals.