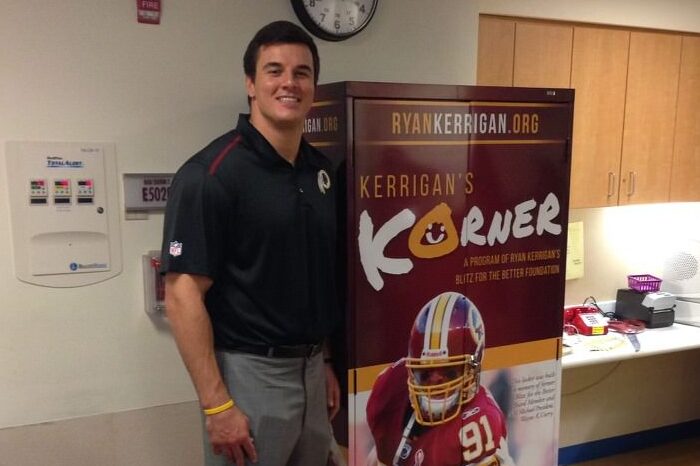

Ryan Kerrigan was a beloved linebacker in the Washington, D.C., area during his 10-year career with the Washington Commanders. The franchise’s all-time sack leader started his charity, Blitz for the Better, in 2013 to help ill and special needs children.

Kerrigan’s foundation generated more than $30,000 in three of its first four years, hosting several events and donating to Children’s National Hospital.

In 2025, though, the charity no longer appears to be active. Kerrigan’s website promised “exciting new features,” but only minor updates were added last year. The charity generated a negative net income in four of the seven years it filed forms with the Internal Revenue Service.

The rise and decline of Kerrigan’s foundation highlights the challenges faced by athletes in their philanthropic endeavors.

These charities allow athletes to support a cause meaningful to them. Former Washington Nationals player Ryan Zimmerman’s foundation focuses on multiple sclerosis treatment in support of his mother, who has dealt with the disease since 1995. Former Olympic swimmer Michael Phelps’ charity benefits youth swimming and mental health.

Other athletes are less vocal about causes they support. Former Washington Commanders quarterback Kirk Cousins has donated hundreds of thousands of dollars to Bethany Christian Services, one of the largest adoption and foster care agencies in the nation, according to his foundation’s tax forms. The organization is known for stances including opposition to abortion rights.

Heading a nonprofit organization is demanding. Even the most well-meaning athletes can be tripped up by time demands, a lack of administrative experience or just bad advice.

In an interview with Capital News Service, Kerrigan attributed the decline of Blitz for the Better to several factors including increased family obligations and less time to give to key functions like fund-raising. He got help from Prolanthropy, a management company that specializes in supporting athletes and their charities. Based on tax records, the charity’s ambitions have not been fully realized.

“There’s certainly a lot that you don’t necessarily understand going into it,” Kerrigan said. “You’ve got to round up your board, you got to figure out different ways to do fundraisers and such….”

The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism reviewed rosters of pro sports teams in the DMV over the past decade and found more than 60 pro athletes, including Kerrigan, who founded a public charity or private foundation.

Incentives for becoming the leader of a charity are powerful. For some pro athletes, they begin with a chance to help and a deep commitment to the causes they support. Other benefits include building a positive image among fans and tax advantages, especially for players who command million-dollar salaries. But if the benefits are extensive, so are the risks.

“You either have a young man who’s completely and totally got their [act] together and he’s got parents who have their [act] together … and they oversee the nonprofit,” NFL agent Seth Katz said. He added that the player’s charity falls short of achieving its mission in other cases “because [the athletes] don’t know how” to lead it.

Katz noted that athletes often underestimate the costs of founding a nonprofit organization.

The Povich Center reviewed documents that tax-exempt nonprofit organizations are required to submit each year to the IRS. The form, referred to as a 990 form, includes information like the nonprofit’s mission statement, expenses, revenues, employees and the number of volunteers who participate.

“There’s much more emphasis for young people today on participating in community service and volunteering than when I was a kid. And with professional athletes making so much more money, their impact is going to be bigger,” said Sarah Fields, a researcher and professor of sports and culture at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Michael Phelps is an athlete who has melded his sports career with his philanthropic goal. At 23 years old, the former Olympian established the Michael Phelps Foundation to “promote water safety, healthy living (mental and physical) and the pursuit of dreams.”

Since its inception in 2008, the charity has added mental health advocacy and partnerships with many organizations, including Special Olympics and Boys & Girls Club of America. Phelps’s charity raised over $1.13 million in 2023, according to the foundation’s tax forms.

Helping others is a motive for most in the sports world who start charities, but it often isn’t the only one. Other reasons, say those who study social responsibility and sports, include reaping tax benefits that go along with charitable giving and polishing up an athlete’s public image.

After being embroiled in negative publicity for participating in “underground” poker games, a form of unlicensed gambling, former professional baseball player Alex Rodriguez hosted a charity poker event with rapper Jay-Z.

“I got in some trouble for poker last year, so why not turn it around and raise some money for the children?” Rodriguez told MLB.com in 2006. Just 1.26% of the more than $403,000 raised from the Rodriguez event went to charity, according to The Boston Globe.

“Athletes are humans and people make mistakes. People engage in behaviors that are socially questionable or unacceptable or even sometimes illegal. One way to soften the blow a little bit is doing good,” said Kathy Babiak, the director of the Michigan Center for Sport and Social Responsibility.

Thilo Kunkel, a researcher and professor of marketing and sports management at Temple University, noted that fan loyalty often increases when athletes go public with their philanthropy.

“When an athlete shares the good they do in the community…people’s perceptions go from generic associations to ones that are focused on the athletes themselves, their personality and character and what makes them unique,” Kunkel said.

The athlete also can gain a feeling of connection.

“It was really cool to see something that you thought might be a pipe dream,” Kerrigan said. “Like, ‘Am I really able to have an impact at all? Let alone a good one?’ It was cool to see that positively come to life.”

Some athletes, like Cousins, direct philanthropy to causes that reflect their religious beliefs and commitments.

The current Atlanta Falcons quarterback and his wife’s charity, the Julie and Kirk Cousins Foundation, donated $250,000 to Bethany Christian Services, according to their 2022 tax filing. The foundation made the same donation in 2019 and a $175,000 donation in 2021.

In addition to adoption and foster care services, Bethany Christian Services provides pregnancy support, and in 2019 ran more than 100 “crisis pregnancy centers” offering tests, counseling and other prenatal services to dissuade pregnant women from abortion. The organization also refused to place children with openly gay prospective parents in most states until 2021.

Cheri Williams, former Senior Vice President of Domestic Programs for Bethany Christian Services, acknowledged the organization’s history of excluding services from openly gay couples in 2022, writing: “The LGBTQ+ community hasn’t always been welcome at Bethany, and I lament that our past practices have made members of this community feel overlooked and ignored.”

The Julie and Kirk Cousins Foundation’s 990 filings indicate a history of donations to organizations that oppose abortion and espouse perspectives limiting LGBTQ rights, including Lakeshore Pregnancy Center and Eternal Perspective Ministries. Between 2017 and 2022, the Cousins Foundation donated over $845,000 to organizations with these ideologies.

Additionally, Kirk Cousins has served as an ambassador for Focus on the Family, which espouses similar ideologies, and appeared on its broadcast channel in 2023, spending a half-hour discussing his Christian faith with the organization’s chief operating officer, Ken Windebank, without explicitly addressing abortion or LGBTQ issues.

Cousins’ agent, Mike McCartney, referred CNS to Ken Filippini, Kirk Cousins’ business manager and the foundation’s secretary and treasurer. Filippini did not respond to three requests for comment via email.

Tax benefits for athletes who launch public charities vary widely. It can depend on whether athletes are contributing their own money to the cause.

Some charities launched by athletes rely mostly on contributions from others. In that case, players receive little or no tax benefit — they’re leveraging relationships and fame to raise money but aren’t contributing their own.

Morgan Moses, a former Washington Commanders player now with the New England Patriots, Alex Smith, former Washington Commanders quarterback, and Dwight Howard, an NBA all-star who played one season with the Washington Wizards, all have public charities that received the majority of their support from donations made by the public, according to the most recent 990 documents available.

In 2017, the Morgan Moses Foundation raised more than $91,000, most of which was raised through public support.

Athletes’ personal donations to a public charity are significant as well, sometimes totaling millions of dollars. For this group, tax implications could be significant.

Since 2015, former Washington Wizards guard John Wall has donated thousands of dollars to his private foundation, the John Wall Family Foundation. In 2023, he contributed more than $386,000, according to the organization’s most recent 990. Wall contributed more than $605,000 in 2022 and nearly $153,000 in 2021 as well.

Cousins and his wife also personally gifted their foundation an average of nearly $6.5 million per year, according to the foundation’s five most recent 990 filings.

Ryan Sklar, a Certified Public Accountant, said that an athlete who supports their charity with their own money gets “an immediate tax deduction on their personal return.”

“If they’re in the 37% [tax] bracket and make a $100,000 contribution, that saves them $37,000 in taxes,” Sklar said.

A predictor of how successful a public charity will be is whether the athlete is committed personally or doing what a team or marketing advisor has recommended as an image-making boost, said Kunkel, the Temple University professor.

“The biggest issue we see is when someone starts a charity because someone else pressures them into doing it or society pressures them into doing it and they don’t really care too much,” Kunkel said.

Still, the vast majority start their charities with good intentions and care deeply about the causes they support, researcher Sarah Fields said, but their philanthropy falters “when they don’t know what they’re doing.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.