Sophia Wilcox’s work to bring her Afghan team to the U.S. has always been difficult. Now the pressure is mounting even more.

The Taliban is targeting Afghans who worked with the U.S., including those who worked with the University of Maryland. Neighboring countries like Pakistan and Iran are cracking down on harboring Afghan refugees. At the same time, President Donald Trump is imposing a freeze on admitting refugees to the U.S.

It’s a humanitarian disaster, and the stakes are high.

“I was sent there, to wake these women up to the idea that they could be or do anything they wanted to if they put their mind to it,” said Wilcox. “We exposed them to the current danger that they’re in,” she said, “we are the reason they’re in that danger.”

Today, from her home in central Costa Rica, Wilcox is reassembling the UMD agriculture team that disbanded in 2017. She’s working with them to raise awareness for the people who she says are hiding in danger and waiting to come to the U.S.

They worked on agricultural projects

Wilcox was the in-country director, and Jim Hanson was the Maryland-based principal investigator for the “Women in Agriculture” program. Hanson ran that program from 2011 to 2017. It was funded by USAID through the UMD’s Department of Agriculture and Resource Economics.

The program taught Afghan women innovative ways to tend gardens and grow, harvest, store and sell food— skills they brought back with them to train other women in their communities. The goal was to increase food security and livelihood.

The Afghan staff supporting the program did an array of work. Some managed the offices and translated for the UMD team. While others provided logistical support and security for them against militant threats. The program had cooks, cleaners, bookkeepers and teachers, and they took on Afghan interns too.

After the program, said Wilcox, many of the staff and interns thrived in their fields. Some went to get higher degrees. Others ran their own businesses. That is, until the Taliban regained control of the country, the Afghan government crumbled and the U.S. withdrew.

Wilcox and Hanson said working with the program put a target on the backs of their Afghan team.

“It’s terrible. I feel terrible,” said Hanson. “Neither Bush nor Obama walked up to these individuals and promised we would be there forever, but no one expected this outcome,” he said. “We were trying to help them build a better life.”

When Wilcox learned that the staff and interns qualified for permission to come to the U.S., she began collecting the paperwork to help.

“We started working nonstop on how to get this done,” said Wilcox.

She organized the rescue project with the help of a former contractor. Wilcox uses a master color-coded tracker to visualize where each individual and family is in the process of coming to safety.

But when the Trump administration suspended the United States Refugee Admissions Program, the colors on Wilcox’s spreadsheet stopped changing. Eighty of the roughly 100 people on her list were still overseas. Most, she said, hiding for their lives.

They left home

Fatemah’s name on Wilcox’s tracker has been highlighted in light blue.

That color means she’s made it to the U.S. safely. She came with her husband and four kids and has a job at a daycare that keeps her busy.

“Their laughter calms me down,” she said about the children at the daycare.

Capital News Service agreed to refer to the Afghans interviewed in this story only by their first names out of concerns for their safety.

At the peak of her career in the northern city of Mazar-e Sharif, Fatemah was a mom, an active professional and an avid caretaker of her small personal farm that took years to build up.

Their home was on the eastern outskirts of the bustling city. From the yard where her family liked to sleep on the raised outdoor mattresses during the summer heat, she could see the mountains, sandy brown and often capped in snow.

Trained in veterinary medicine, Fatemah ran a veterinary pharmacy and led a women’s veterinary association, helping women overcome hurdles in experience and knowledge in the field.

When the Taliban took over, all that changed.

The U.S. considers the Taliban a foreign terrorist group that has fought for power in the country since the 1990s.

Fatemah said she began hiding her work as a veterinarian with an international nonprofit organization to avoid being arrested at Taliban checkpoints.

The Taliban forbade women from working with foreign aid organizations. So to get to work safely, Fatemah would disguise herself as a doctor, she said, a profession still permissible for women then.

The alternative, sitting at home after years of building her career, is something she said she could never accept.

Wilcox, she said, is one of her role models.

While treating sick animals one weekend afternoon in a district on the other side of the city, Fatemah got a phone call from people identifying themselves as members of an international aid organization that helps with resettlement, she said. The caller said it was time for her and her family to leave and asked her to send copies of everyone’s passports.

She immediately dialed her husband, Sayed Hosein.

Worried it could be a trick, he said he nervously told her to proceed. Fatemah used scans that were stored on her phone, sent them to the aid organization and said she received copies of their ticket to Kabul. That’s where they would undergo final evaluations before leaving for the U.S.

Instructed to stay extremely tight-lipped about their pending exodus, Fatemah said she tried to act normal for the remainder of her time on the job.

When Sayed Hosein picked her up, he could see her face was flushed.

“Wife, please relax,” he said. “It’s not a problem.”

They drove home in silence. Sayed Hosein would have to sell his car and organize a ride to the local airport. Fatemah would need to rush out that night to buy suitcases and make sure she and the kids were packed.

Neither of them slept that night.

The sun was just coming over the horizon when a neighbor came to take them to the airport. Fatemah could not say whether she looked back one last time or not at everything she had built for herself and her family over the past 21 years. Instead, she fell silent trying to contain her tears.

They’re still waiting

If someone is not highlighted in light blue on Wilcox’s list, they are not in the U.S. Some have made it to safer places – Canada, Europe. The bulk are laying low in Afghanistan waiting to hear any update on their cases.

Diba is hiding in Pakistan.

Her father worked as a driver for Wilcox’s team. That was a job, Wilcox said, that entailed learning how to evade kidnapping attempts and roadside bombs.

When Diba first met Wilcox, she was still a high school student in Kabul. Those days she loved to play soccer and enjoy the Kabul street food.

Wilcox helped Diba seek treatment for a blood disease, thalassemia, through the help of an aid organization.

The planned bone marrow transplant never happened, Diba said, because the doctors thought she was too old for the treatment to be successful. She still deeply values Wilcox’s intervention. Today, she manages the blood condition with blood transfusions and medicine to regulate levels of iron in her liver.

“Ms. Sophia,” she said, speaking about Wilcox, “is an angel and the hero of my life.”

Diba said she, her parents and siblings drove to Pakistan in the summer of 2022, because of threats from the Taliban. It took a whole day. Now Diba and her family are waiting to hear when they can fly to the U.S.

Wilcox raises funds to help keep a roof over the family’s head, and Diba said they borrow money from relatives to sustain them. The longer they stay in transition, the tighter the money gets, said Diba. Food, medicine and additional visa fees all strain the family’s budget, forcing them to make tough sacrifices.

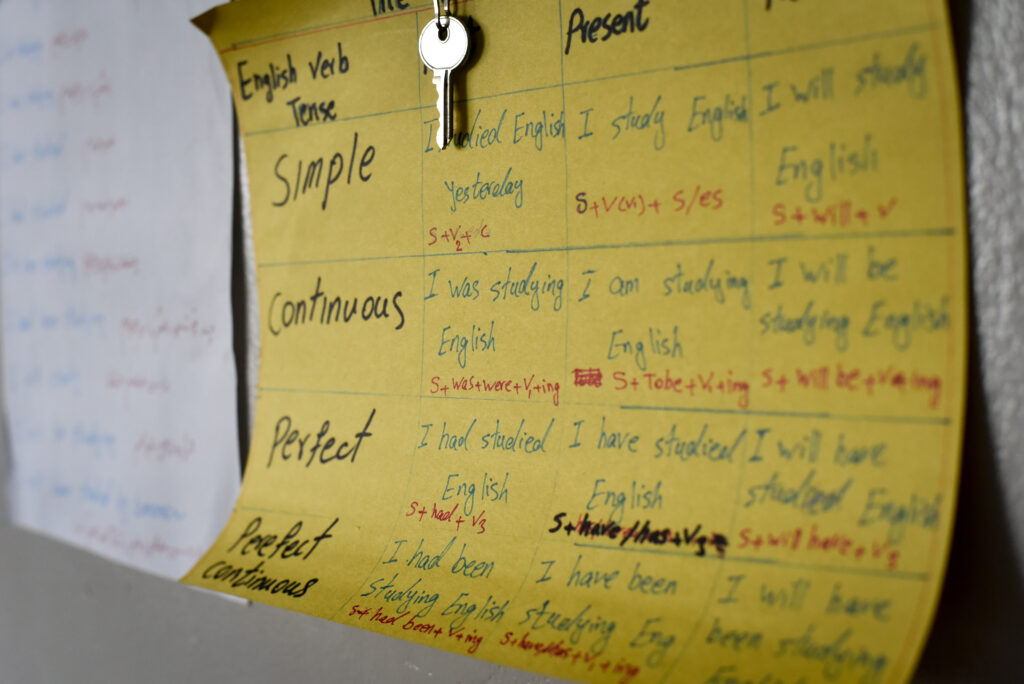

Much of her time is spent waiting, despite the family having already undergone the necessary evaluations to leave, she said. She practices English in her spare time.

“I don’t check my email every day,” she said. “I check it every hour, but unfortunately there are no updates.”

Diba and her family stay indoors as much as possible to avoid Pakistan’s authorities, especially after Pakistan started sending Afghan refugees back to Afghanistan. She said she battles depression. Diba hopes to come to the U.S. and start a foundation that helps people with thalassemia receive the treatment she could not.

“Life in Pakistan is getting harder and harder,” said Diba. “When I wake up in the morning, I say to myself, ‘I wish I was allowed to go to university like other girls.’”

They’re organizing

In Washington D.C., Kristyn Peck, Chief Executive Officer of Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area said today’s climate for resettling refugees in the U.S. is difficult.

LSSNCA is one of the largest resettlement organizations in the greater Washington area. The Trump administration froze funds and contracts, said Peck, placing significant financial strain on resettlement agencies caring for recently arrived “new neighbors.”

Peck says every major faith group has a calling to welcome people who flee violence.

“I think about World War II, Jewish refugees who were arriving on boats and were sent back,” said Peck. “That’s what we’re doing now. We’re preventing access to protection for people who are fleeing life and death scenarios who are fleeing persecution and violence”

Peck said the LSSNCA has seen an outpouring of community support since funding cuts hit. Local residents who want to make a difference, she said, can volunteer with the organization’s Good Neighbor Partners and Champions program. She’s also encouraging people to share real life stories of impact with their representatives.

“I think people are feeling a sense of helplessness right now,” said Peck, “and I think the antidote to that is helping.”

In Costa Rica, Wilcox, who is focused today on raising awareness for the Afghans, knows the transition to life in the U.S. won’t be easy for the people she’s helping get here. She’s in touch with her Afghan team and said people are suffering.

Some are sick like Diba, whose family has to decide between food and medicine, Wilcox said. Others are suffering severe depression and can barely speak with her.

Wilcox is especially worried about those facing deportation back to Afghanistan.

“You read the research from people like Human Rights Watch and other similar types of organizations,” she said. “They say arrest, torture, and possibly death.”

Wilcox is putting together a video package that she’ll deliver at a conference she and her fellow agricultural professionals are calling The Right to a Safe Home. It will take place at the end of April in College Park, Maryland. She wants to draw attention to the people in the waiting process – a process she called opaque, random, and nearly impossible to navigate.

“We were there with our white faces and our funny ways and exposed them to all the dangers, and the U.S. government promised that we would take care of them, and it’s now breaking that promise.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.