On Sept. 1, 2021, California enacted a law that changed sports forever.

The Fair Pay to Play Act gave athletes playing for California universities the right to earn money from their Name, Image and Likeness. For the first time, they could retain their eligibility to play sports while being paid for signing an autograph, posting on social media and pitching a product.

Three years later, college players across the country are cashing in — and so are high school athletes.

Where are high school NIL deals allowed?

In 41 states and Washington, D.C., any high school player — from a quarterback to a soccer goalie — can have an NIL deal. A few other states permit NIL on a highly restricted basis — Arkansas permits it only for high school athletes who have been accepted into an Arkansas college or university.

Soon, NIL could be the rule in all 50 states and Washington, D.C.

A record eight million athletes played high school sports in the 2023-24 academic year, according to the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS). With that large number of athletes comes a wide range of opinions on whether NIL is positive for high school athletics.

“I truly believe that most high school students, or a lot of students, should play for the love of the game,” said Steve Savarese, who served as the Alabama High School Athletic Association Director from 2007 to 2021. “Once you receive compensation for your participation in sport, it becomes a degree of professionalism.”

Proponents of NIL, on the other hand, say that high school athletes are entitled to profit from the acclaim that follows them.

Sports economist Andy Schwarz, a co-sponsor of the Fair Pay to Play Act, said withholding those rights from high school players reflects an “un-American” viewpoint.

“It only makes sense [to deny NIL deals] if you believe that it’s fundamentally bad to earn a living,” Schwarz told Capital News Service.

Savarese predicts a list of “unintended consequences” if NIL comes to Alabama, most of which would be damaging to high school sports. That includes the potential neglect of girls’ sports, which he believes would result from heightened attention for football and boys’ basketball.

“In our state — the football-crazy state we live in — the football programs will always have money,” Savarese said. “Our other sports, our female athletes, our female programs, if money is given to individuals rather than the entire program at a school, I think there could be those unintended consequences.”

Wyoming, which has 21,213 high school athletes according to NFHS, also does not permit NIL, although attitudes are changing.

In an interview with Capital News Service, Trevor Wilson, commissioner of the Wyoming High School Activities Association, said he strongly opposed NIL four years ago but has since done a “180…on this whole thing.” Wilson said he now sees value in high schoolers learning how to earn money to help pay for books, tuition or other minor expenses.

“I’m hoping we can come up with something that’s fair and makes sense for our students, and they don’t get put in a bad spot,” Wilson said.

Wyoming hardly would be alone in reevaluating NIL. In 2024, at least eight state high school athletic associations changed their rules to allow NIL. (No state that has adopted NIL has reversed course to prohibit it.)

National poll shows majority support high school NIL

Just four years after the first NIL deals — and three years after Nike signed its first high school athletes — most Americans seem to accept the idea of high school athletes as endorsers and influencers.

A 2023 national poll conducted by the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism, The Washington Post, and the Center for Democracy and Civic Engagement at the University of Maryland revealed that 54% of Americans believe that high school athletes should be allowed to earn money through endorsement deals. Support was higher among respondents who are Black (74%) and Hispanic (73%).

In the poll, support for NIL for children before high school came to less than 50% overall. A majority of Black and Hispanic respondents, however, said they were in favor of pre-high school NIL, with 60% of Black respondents and 56% of Hispanic respondents approving of it.

Schwarz, who has written extensively about sports, economics, and athlete rights, said that the differing viewpoints reflects a long-standing “prejudice against athletes making money.”

“If a particular financial benefit feels like it goes disproportionately to minorities, we’re oddly against it in America,” he said.

Lack of data makes impact of NIL hard to determine

The impact of NIL on high school sports is unclear. That’s due in part to a shortage of data — no national organization comprehensively tracks NIL at the high school level.

The NFHS has record-keeping on sports participation. It can tell you how many girls are playing 11-player football in Alaska (five). But it does not track NIL policies. Dan Schuster, NFHS Learning Center Director, explained that the organization “is not in the requirements business.”

“The state athletic or activities associations, they’re the ones that really make the requirements or don’t make the requirements,” Schuster said.

NIL activity also is not tracked closely by state associations. All 50 states have at least one athletic association that makes policies for high school athletes. Rules about reporting NIL deals vary across those associations.

An analysis by The Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism and The Howard Center for Investigative Journalism revealed that no two state NIL policies are the same. Some span more than a page of the association’s handbook, some are a few sentences and some associations have no NIL language in their policies.

More than half of all states explicitly prohibit NIL deals with companies that sell drugs, gambling or firearms, while others include language that seems to rule out these categories, but the language is not uniform.

Penalties for breaking NIL rules also are far from standard. Some states have three-strike systems, meaning that a third violation generally results in the athlete losing their eligibility to play sports for their high school. Other state associations have adopted a zero-tolerance stance — one violation and the athlete is penalized. A few states that allow NIL appear to have no published rules for punishing violators.

High school stars can rake in dollars with NIL deals

A policy common among most states that permit NIL is a ban on athletes using school intellectual property in their NIL work, including team uniforms and logos. Most do not allow players to be pictured on school property for their promotional work. For instance, an athlete may sign a contract to appear in a commercial for the local restaurant, but the commercial could not be filmed on the team’s home field and they could not wear their game jersey. The commercial could not include any clips from league-sanctioned games or feature a cameo from the school mascot.

Still, the sheer magnitude of deals with some of the biggest pre-college names in the country have led to publicity for the schools where those players compete, even if no state policies were violated.

As state high school associations regulate NIL, elite athletes are pulling in dollars that only a few years ago would have been reserved for top pro athletes. Lakers guard Bronny James, whose superstar father LeBron has played 22 seasons in the NBA, signed a reported multi-million dollar deal with Nike when he was a senior at Sierra Canyon School in Los Angeles. Cameron Boozer, son of former NBA All-Star Carlos, who has committed to attend Duke University in the fall, has a NIL valuation of $1.6 million according to college and high school sports media website On3.com.

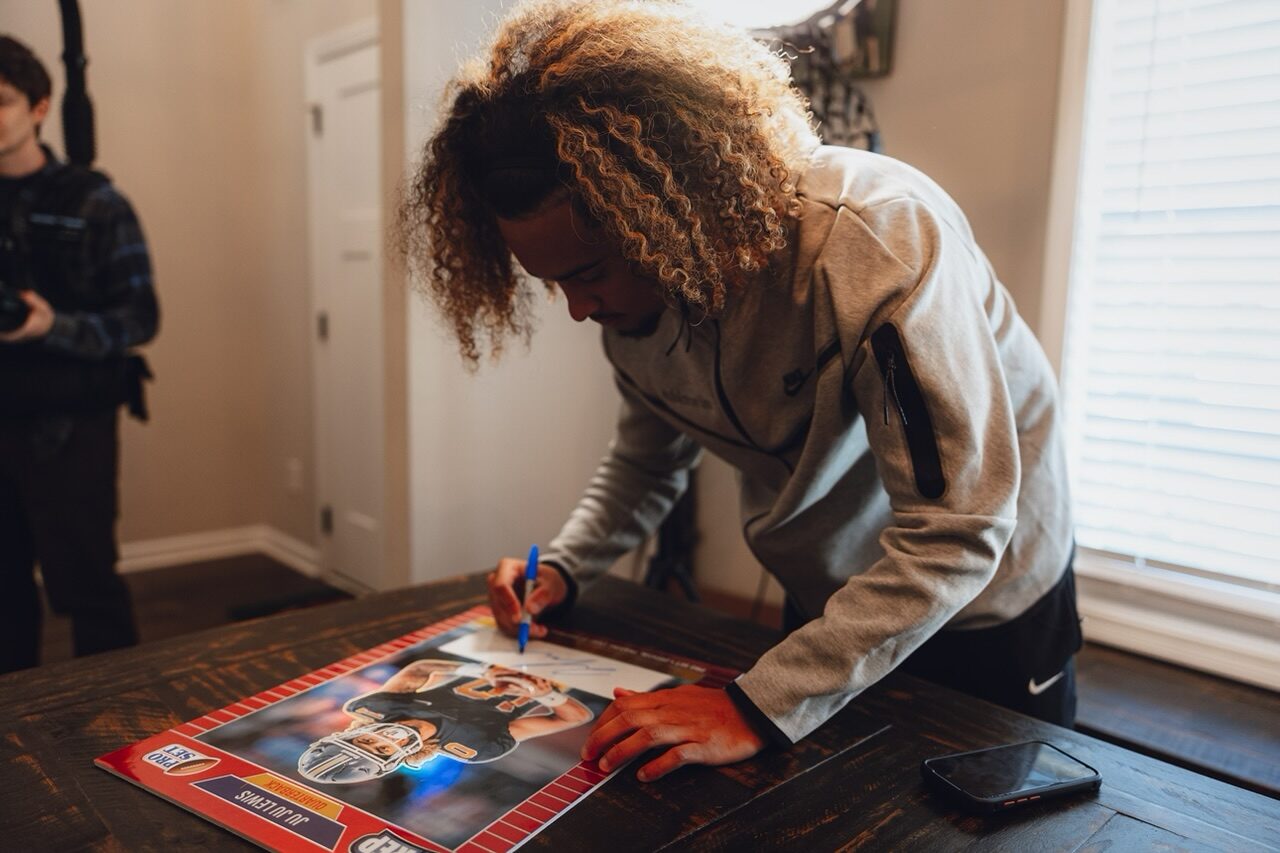

Julian “JuJu” Lewis, ranked 12th on ESPN’s list of the top 300 football recruits nationwide for the class of 2025, cashed in as a high school player in Georgia by signing a deal with Leaf Trading Cards, a Dallas-based trading card company. Not long after, Lewis brought attention to the brand by displaying one of his signed cards during an interview on The Pat McAfee Show, a widely watched sports interview and commentary program..

“NIL really became an opportunity to go after some of these kids before they were huge stars, so that we could build relationships with them, get to know them, get to know their family,” Leaf President Josh Pankow told CNS.

Leaf has agreements with 50 to 60 high school athletes, Pankow said. They include recent top quarterback prospects Jaden Rashada, Trae Taylor and Lewis. Leaf also made a deal with Bella Rasmussen, a star female football player in California who graduated high school in 2023.

Still, high school NIL is in its infancy. In the 2023 Povich Center-Washington Post-CDCE survey, only 7% of respondents said they had seen a high school athlete endorse a product or service on TV or social media. The percentage of athletes with such deals is low, though tracking of NIL in high schools is inexact.

Dan McMahon, principal at DeMatha Catholic High School in Hyattsville, said that of the roughly 650 students playing on sports teams, he is aware of just two who have had NIL deals. One was the star quarterback during the 2024 season for the Stags’ football team, a perennial power in the Washington Catholic Athletic Conference. The student, Denzel Gardner, is committed to playing football in the fall at the University of Southern Mississippi.

McMahon sees a future in which NIL gains momentum and more DeMatha players have deals. “My guess is in two years, that number will be eight or 10 kids. And two years after that…..”