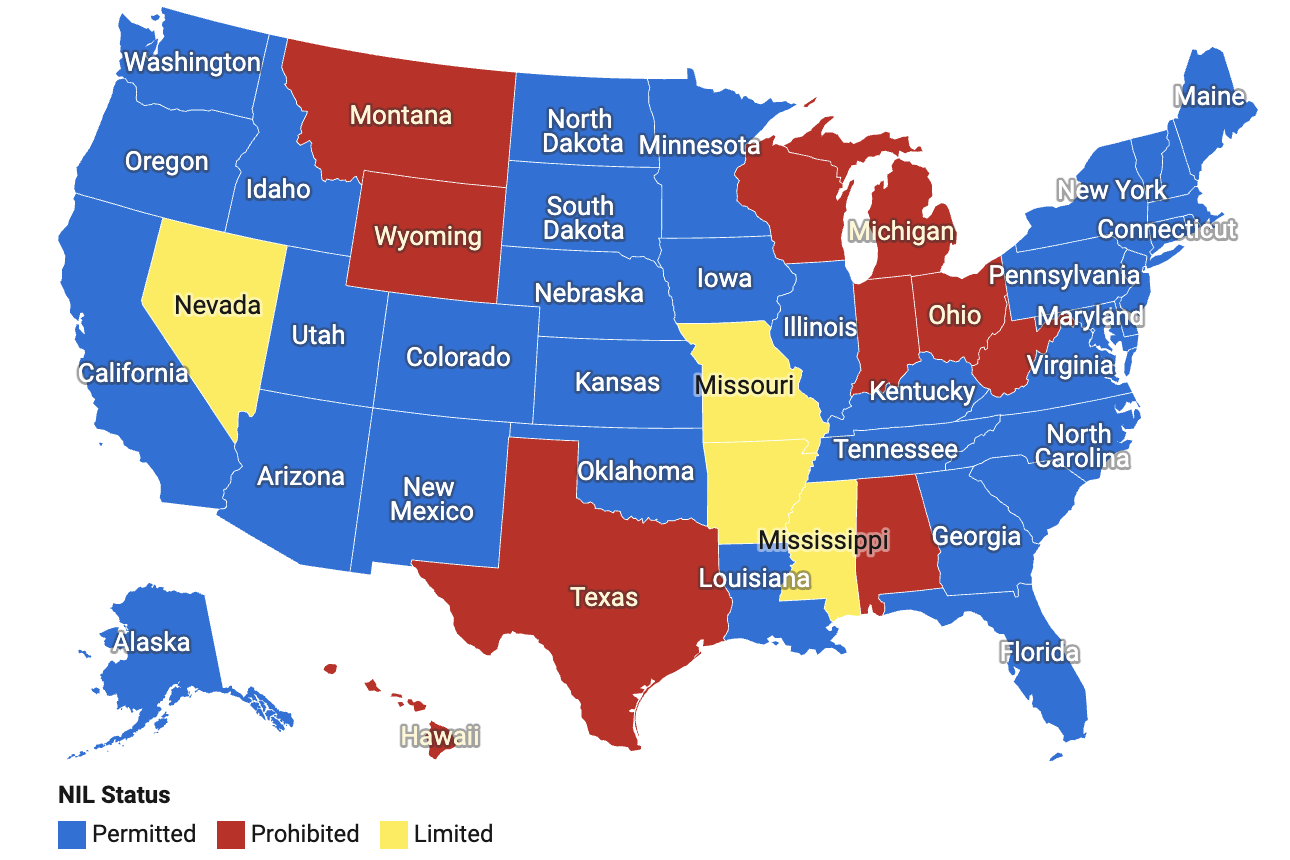

Name, Image and Likeness (NIL) is more the rule than the exception in high school sports. In 41 states and the District of Columbia, high school associations permit athletes to be compensated for appearing in advertisements and for using social media to pitch products. Four additional states permit NIL on a highly restricted basis.

An analysis by the Shirley Povich Center for Sports Journalism at the University of Maryland reveals a patchwork approach to regulating NIL.

In notable ways, state athletic association policies are similar, even identical. All prohibit mentioning an athlete's school or team as part of an NIL deal. They also prevent athletes from signing professional contracts or receiving performance-based incentives while participating in high school sports.

Similarly, over half of the current NIL-permitting state associations explicitly prohibit entering endorsement deals related to tobacco and alcohol products. Other commonly cited prohibited categories pertain to cannabis, lottery and sports gambling, weapons, adult entertainment and prescription pharmaceuticals.

High school NIL rules, though similar from state to state, diverge in important, sometimes unexpected ways. Some notable differences include deal reporting requirements to athletic and academic administrators (or a lack thereof) and an athlete’s ability to collect compensation earned in the Olympic Games.

In the four states in which NIL is highly restricted, including Mississippi, Arkansas and Missouri, athletes must navigate rules such as being eligible for NIL only after signing a letter of intent to a college or university in that state.

State-specific variations in NIL reporting regulations

Only five of the 42 NIL-permitting athletic associations — Arizona, Delaware, Georgia, Pennsylvania and Virginia — specify when an athlete must report entering an NIL deal to a school administrator.

Georgia allows the most time, requiring an athlete, parent or guardian to notify a school principal or athletic director within seven days. Arizona requires the student or guardian to inform the school’s athletic director within five school days.

Pennsylvania, Delaware and Virginia require notification within 72 hours of signing a deal. Only Virginia requires a principal or athletic director to be notified in writing. The District of Columbia State Athletic Association also requires written notification but does not offer a reporting deadline.

There are also differences among states regarding the involvement of a parent or guardian in NIL deals or for a school to be notified. For example, most NIL-permitting states, including California, Florida and New York, do not specify that athletes or their guardians must notify athletic, school or state administrators of entering an NIL agreement.

Just nine NIL-permitting states share guidelines mandating some degree of notification to administrators. Those include the five states that demand timely notification of NIL agreements, as well as Oregon, Connecticut, North Carolina and Massachusetts.

Instead of giving explicit directions, states such as Iowa encourage parents and athletes to receive outside legal counsel and tax advice. Iowa also recommends that those parties seek guidance from the athlete’s member school.

How five states handle NIL violations

The most common forms of punishment faced by players who break NIL rules include potential loss of amateur eligibility, obligations to return earned funds, and suspension from athletic participation.

Schools can be sanctioned, too.

Five states — California, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, South Carolina and Florida — use three-strike policies with escalating penalties for repeat offenses. Of the five, only Pennsylvania suspends the offending athlete on their first violation.

Florida is also the only state among those that includes penalties for schools, employees and contractors, and it contains language specifically about “falsifying information” related to NIL deals.

Operation Gold: Evolving rules for Olympic-bound athletes

At the 2024 Paris Olympics, six high school athletes joined the ranks of Team USA to compete on the world stage.

Previously, amateur athletes competing in the Olympics often waived monetary prizes earned from competition to maintain their amateur status. Six states have amended their NIL and amateurism guidelines, enabling high school athletes to be paid by the United States Olympic and Paralympic Committee’s Operation Gold program.

Connecticut, Wyoming, Maryland, New Jersey and Pennsylvania created exceptions to allow high school athletes to collect Operation Gold funds.

Texas, which currently prohibits high school NIL, also permits athletes to accept funds “administered by the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) or other national governing body.”

Alaska, an NIL-permitting state, waived amateurism restrictions for athletes “participating as members of official United States Olympic Teams,” but did not include guidelines for compensation earned from participation at that level of competition.

Expanding NIL opportunities: Digital assets and instructional roles

Although states generally agree on permitted NIL categories, Maryland, Vermont, North Carolina and Massachusetts allow their athletes to promote non-fungible tokens (NFTs), which serve as digital ownership certificates for assets such as artwork or collectibles, including trading cards.

Hosting youth training camps or instructional clinics is another alternative to traditional NIL activities. But states remain divided on their use. For example, Kentucky, Missouri and South Carolina are among several states that permit athletes to participate in coaching or officiating opportunities if their earnings do not violate school-affiliated NIL restrictions.

New Jersey, an NIL-permitting state, deviated from its peers by banning its athletes from running or profiting from sports camps. This policy prevents NIL opportunities from extending into paid instructional roles.

Holdouts and the road ahead

High school state athletic associations across mostly southeastern states like Florida, Georgia, South Carolina, Mississippi and North Carolina have approved NIL activities within the last two years, leaving only ten states as holdouts nationwide.

The most notable holdout is Texas, with over 850,000 high school athletic participants during the 2023-24 school year, ranking it first among states, according to figures from the 2023-24 National Federation of State High School Associations Participation Survey, a leading advocacy nonprofit for high school athletics.

The Midwest is the region with the largest number of remaining NIL-prohibiting states — Michigan, Indiana and Ohio — while the rest include West Virginia, Wyoming, Montana, Alabama and Hawaii.

As of May 2025, athletic associations and legislatures in these states are still divided on adopting NIL at the high school level.

For example, the Michigan House of Representatives passed HB 4816 in 2023, voting to extend NIL privileges granted to college athletes to high schoolers. The bill has comprehensive guidelines for permitted and prohibited NIL activities and requirements to provide notice of entering NIL agreements to a Michigan High School Athletic Association (MHSAA) representative. Yet, the bill still awaits a vote in the Michigan Senate and, as a result, NIL activities remain banned by the MHSAA.

In January, the Montana High School Association approved an amended bylaw permitting athletes to profit from NIL. Whether the new rule goes into effect depends on approval from the Montana Legislature.

Consensus and clarity regarding these policies are even more imperative as the United States experiences its highest high school athletic participation totals.