By Mary Clare Fischer

Capital News Service

Return to Locust Point: A Changing Waterfront

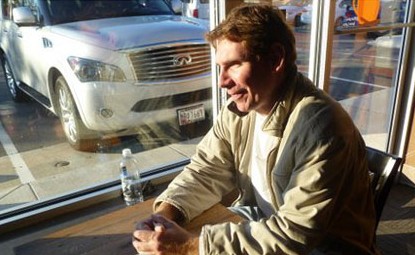

BALTIMORE – John Shea had lived in Locust Point for less than two years when two Francis Scott Key middle-schoolers got into a fight last spring, and the video went viral. Suddenly, a lot of negative attention was focused on the neighborhood — and Shea was concerned.

“When things like that blow up and give the school a black eye, it gives the community one, too,” he said.

Though he doesn’t have kids in school — his daughter MacKenzie is 2 years old — and though he’s relatively new to the neighborhood, Shea, 40, has become chair of the Locust Point Civic Association’s new education committee.

He helped choose the school’s new principal. He leads Saturday cleanups of the grounds. He’s helped empty rooms of old textbooks. He’s planning fundraising, and he talks up the school to everybody he meets.

For John Shea, a strong neighborhood needs a strong school.

“It’s about trying to connect with people in the community — create that network and make it a strong link,” Shea said. “We need people who are reliable and dependable and want to turn it around. We know it’s not going to happen overnight so we’re starting our efforts now.”

Most importantly, he wants to change the neighborhood’s perception of the school by transforming the “climate” in the school for the students. He said small changes, such as a new policy that children line up quietly to change classes have helped remind the students that school is a place to learn. And this year, no fight videos have made their way to YouTube.

It’s the message they’re trying to send to pupils within the school: “It’s time to focus on what’s happening inside the school walls. It’s not the time to be rambunctious and bouncing around,” he said. “Let’s be serious about what we need to learn today and how we want to move forward tomorrow.”

Shea wants to turn Francis Scott Key into a National Blue Ribbon School, a designation awarded by the U.S. Department of Education to schools where students are achieving at a high level and/or vast improvements have been made.

“That’s the one building block,” Shea says of public education. “That’s the one thing that all kids can have. Not everyone goes to the NFL and not everyone goes to the NBA, but everyone can still go to college and still be a productive member of society.”

Organizations including the Downtown Baltimore Family Alliance and Under Armour have become involved in partnerships with the school. Shea hopes this will help focus attention on Francis Scott Key and result in higher test scores as well as an atmosphere that feels safe for the students.

He said he’s never considered that his efforts might fail. He thinks that’s a “deflating” way to look at the world. He said that at every civic association meeting, more and more residents are saying they want to get involved.

A thick Boston accent gives away Shea’s background. Raised in Milton, Mass., outside Boston, Shea said his parents — his mother was a nurse and his father worked in insurance — were busy but paid attention to their children’s education.

They sent him and his brother and two sisters to the same public schools all the way through to college. He said they told him he could switch to private school if he wanted to, but he never did.

He obtained a degree in business management from Providence College in Rhode Island and worked in various jobs in financial services around the country before moving to Middle River, when he and his wife, Shari, were engaged in the fall of 2007. The couple moved to Locust Point in 2009, to be closer to the city and to give his wife an easier commute to her job in Silver Spring.

“We were looking to move closer to D.C. in the Ellicott City area and just weren’t finding anything we liked,” he said. “We kept reverting back to the city every time we wanted to go to dinner or take a walk. (Locust Point) seemed like more of a community or more of a neighborhood.”

Shea worked remotely for his previous employer — State Street Bank in Boston — for three years, but branched out into a new career in general construction when his daughter was born in fall of 2010.

He said he’d always been interested in education, but now he had to start thinking about where to send his child to school.

“To get involved now is a logical step from my perspective, because you want to be able to be an agent of change, and that’s not going to happen in a day or two,” Shea said. “You need to put in the effort and help turn things around, and then when the time comes for her to be school-ready, we’ll have options.”

He’s looking at everything from clean-ups to curriculum. Shea and other residents have brought rolling dumpsters to Francis Scott Key and helped move some of the heavier trash, deciding what items should be saved and what should be thrown away.

Shea also writes for the civic association’s newsletter, which is online and also hand- delivered to every Locust Point household once a month, highlighting any developments at the school to try and attract parents.

The school’s new principal, Mary McComas, said Shea even spent several hours weeding and trimming the bushes outside Francis Scott Key before the first day of school in September after she said she was worried they would be ignored.

“I don’t even have words for how impressed I was with his level of commitment, especially knowing that he didn’t even have children here yet,” McComas said.

Kate Williams, another resident who has also been working to reinvigorate the schools, said she thought of Shea when her 5-year-old daughter received a citizenship award from Francis Scott Key.

“John Shea would get a very solid citizenship award,” she said. “He’s going the extra mile, and he doesn’t have to. He very easily could sit and go, ‘I’ll think about it when my daughter’s closer to school age.’ Instead, he’s taken the initiative to pound the pavement and get some things organized for the school that I think are really amazing.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.