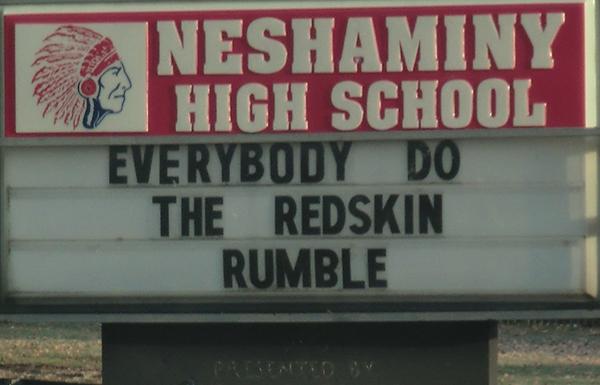

COLLEGE PARK, Maryland — Either publish the word Redskins or don’t print the paper at all.

That was the choice school administrators at Neshaminy High School in Pennsylvania presented to student newspaper Editor-in-Chief Gillian McGoldrick when the newspaper balked at using the name of the school’s official mascot.

McGoldrick and the paper’s staff went rogue. They printed the paper without using the name, prompting the principal to seize copies of the paper and later suspend McGoldrick as editor-in-chief for a month.

“I knew that there would be backlash,” McGoldrick said of the June 2014 decision. “I mean, we were defying a directive from the superintendent and the principal.”

At several high schools that have dropped the name Redskins in recent years — or, like Neshaminy, schools that are debating whether they should continue to use the name — students were deeply involved at every step of the process. In some towns, they led protests against changing the name. At others, they pushed for change and helped select a new team moniker.

- At Goshen High School in Indiana, at a time when the community sentiment about the nickname was split, a committee of 24 students helped lead the move away from the use of the name. The effort was successful, at least in part because “adults get (angry) at other adults, but they don’t get mad at kids,” according to Principal Barry Younghans.

- At Paw Paw High School in Michigan, athletes opposed to the change showed up after practice, some wearing Redskins apparel, at a board of education discussion about changing the name. The board voted 4-3 to keep the name.

- At Conrad Schools of Science in Delaware, students were asked to vote on new nicknames after the decision to abandon the name had already been made. They became the Red Wolves, a reference to the local Lenape Indian Tribe’s “wolf clan.”

At Neshaminy, a school of about 2,500 students in southeast Pennsylvania near the New Jersey border, the debate over the student newspaper’s use of the name has been deeply intertwined with a parallel effort to change it.

The seed for the battle between the student newspaper and school administrators was planted when Neshaminy parent Donna Fann-Boyle began denouncing the nickname at school board meetings in 2012.

Fann-Boyle, whose youngest son entered Neshaminy High School in the fall of 2012, spoke at over a dozen meetings, but she failed to convince the school board to stop using the name.

So in 2013, she filed a complaint with the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, an agency that enforces state laws prohibiting discrimination, setting off a legal battle that continues today.

“To have non-native students dressing up in headdresses and painting themselves, it’s a stereotype,” Fann-Boyle, who is part Choctaw and part Cherokee, told Capital News Service. “It’s like you’re saying, ‘This is what we see Natives as, we don’t see them as modern, productive citizens and a part of modern society.’ They’re stuck in this time warp.”

Fann-Boyle’s actions caught the attention of the editors of the Neshaminy monthly school newspaper, the Playwickian, a name related to a local Native American tribe.

“We started listening to (Fann-Boyle), and then we started having debates about (the name) and like, if it was racist,” said McGoldrick, a Temple University junior who was editor-in-chief from 2013 through her graduation in 2015. “We would have debates after school and one side of the room was for the mascot name and the other was against it.”

The debates led to the paper’s editorial staff deciding in the Fall of 2013 — by a 14-7 vote — to edit out or redact the “Redskins” name in future editions of the paper. The Playwickian ran side-by-side editorials — one for the change, one against — to explain the decision.

There was significant backlash from the student body, said Tim Cho, a 2016 Neshaminy graduate who became editor-in-chief after McGoldrick graduated.

“There was a lot of criticism over whether or not we liked the high school, whether we felt as if Neshaminy High School was a good place to be,” said Cho, who supported the decision to stop using the name. “Because a lot of students equated the high school with the mascot itself.”

A few days after the editorials ran, principal Rob McGee emailed the newspaper’s faculty adviser that he would “ban the ban” of the name, as McGoldrick put it.

McGee did not return several phone messages and emails from Capital News Service.

In November 2013, McGee told the Associated Press he considered the editors’ motives in refusing to use the name as “valiant” but saw the situation as “a First Amendment issue running into another First Amendment issue.”

Chris Stanley, the school district’s community relations coordinator, declined to comment.

For several months, the paper’s editors got around the ban by simply editing the word out. “It was such an easy switch” changing the “Neshaminy Redskins” to the “Neshaminy football team”, McGoldrick said. Then, in June 2014, Neshaminy student Stephen Pirritano submitted an editorial to the Playwickian denouncing the paper’s policy, calling it “Stalinesque.”

“No student has the right to censor another; in our paper, every student has an equal right to expression allowed under the First Amendment,” Pirritano, who died in 2016, wrote in a letter published by The Morning Call newspaper.

The Playwickian decided to publish Pirritano’s editorial, in which the word “Redskins” appeared several times, redacted to read “R——-”. When it submitted the issue to school administrators for review, McGee and then-Superintendent Robert Copeland made clear that the paper had just two choices, according to McGoldrick: publish the paper with the editorial and the word intact — or don’t publish at all.

Copeland, now superintendent of the Lower Merion School District, did not respond to multiple requests for comment. McGoldrick said it was a staff decision to print the paper with the letter from the editors, but she personally sent the final go-ahead to the printer with an email.

“I knew that this was the best decision,” she said. “I made sure to sign my name on the email (to the printer) because I didn’t want anybody else to get in trouble.”

McGee initially confiscated some copies from the school’s hallways. He later relented and allowed the paper’s staff to hand out copies of the paper at the 2014 graduation, according to McGoldrick. Copeland called the confiscation of 40 copies of the paper “prudent,” according to a story in the Philadelphia Inquirer.

McGee eventually suspended the paper’s faculty adviser, Tara Huber, for two days, and suspended McGoldrick from her editor-in-chief duties. Huber could not be reached for comment. McGee also cut funding to the paper, at the approximate cost of the June issue.

Around the same time, the district amended its policy that regulates the student newspaper. The policy now requires editors to submit the paper for prior review earlier than before and gives administrators the right to prohibit publication of material “for any reasonable reason.”

The new guidelines also provided some protection from discipline for student editors for editorial decisions, including “the deletion of the word ‘Redskin’ from any article or editorial or for objecting to its use in any advertisement.”

While the Playwickian controversy was playing out, Fann-Boyle continued trying to get Neshaminy High School to change its name.

Fann-Boyle resolved to push for a change when she saw the word and Native American imagery everywhere on Back to School Night before her son’s freshman year in 2012. “I had to speak up, I had to say something,” she said.

The legal division of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission found probable cause in May that the use of the name in the Neshaminy School District violates the Pennsylvania Human Relations Act, which prohibits discrimination because of race or ancestry, according to David Dickieson, an attorney at Schertler & Onorato, who is working with the human relations commission on the case.

The human relations commission declined to confirm the finding of probable cause because the case is open, said Christina Reese, a commission media representative.

Neshaminy School Board member Stephen Pirritano, the father of the student who wrote the editorial arguing against the newspaper’s policy, told Capital News Service in an email, “Neshaminy has always and will continue to be supportive of and display our heritage in a prideful and dignified manner…Neshaminy is a place (where) all peoples’ come together, where the bonds of community make this a special place of growth and opportunity for all.”

The case will next go to a public hearing, likely next year, where each side will present expert testimony on the impact of the name on students, according to Dickieson.

At the student newspaper, the debate over using the name has continued.

In April 2016, then-co-managing editor Jessica McClelland submitted an article about the school’s annual male beauty pageant, called “Mr. Redskin.”

The paper’s editors voted to redact the word, against McClelland’s wishes. She appealed to the principal, who upheld her appeal. He directed Tim Cho, the new editor-in-chief following McGoldrick’s graduation, to publish the article on the paper’s website with the word.

“I was always taught to stand up for what I thought was right, not for what was the easy way out. The easy way out would have been to redact the word,” McClelland said in a Facebook message to Capital News Service.

Cho, now a student at New York University, published the article with the name redacted. That prompted school administrators to revoke the editors’ access to the website and change the article to include the word.

“It was my belief that the editors have the authority to determine what the guidelines for editing and publishing are, whereas the principal’s role is more of a watchdog,” Cho said of his decision, in a Facebook message to Capital News Service. “If we had complied with the principal’s directive without challenging it, I feared it would have set a dangerous precedent.”

This time, the consequences were different. No one was suspended and the paper didn’t lose any funding, but the story remained online in its unredacted form. A month later, Cho graduated and then-junior Grace Marion succeeded him as editor-in-chief. School administrators returned access to the website to Marion, but it was a conditional return.

“I had to be completely supervised by my adviser at all times and the adviser had to change the password after each login so there could be no tampering,” Marion said.

A year and a half later, the issue is still not completely settled. Marion said she’s told the staff to go back to writing around it, as they had in 2014-2015. “I’ve told the writers to avoid (the name) like the plague.”

-30-

You must be logged in to post a comment.