By CAITLIN JOHNSTON and CARL STRAUMSHEIM

CNS Special Report

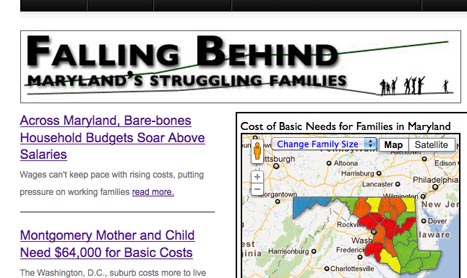

View the full project: FALLING BEHIND Maryland’s Struggling Families

COLLEGE PARK – A Montgomery County family of three — an adult, a preschooler and a school-age child — needs about $78,000 just to make ends meet, a new report shows. And, without government assistance, minimum wage barely gets them a quarter of the way there.

The 2012 Self-Sufficiency Standard calculates the cost of living for Maryland families by looking at the price of such necessities as housing, food, transportation and child care. The report, prepared for the Maryland Community Action Partnership, found that median wages in Maryland have failed to keep up with the increasing costs of basic needs.

While those costs increased statewide by 54 percent since 2001, median earnings failed to rise accordingly, increasing only 25 percent.

The result: a real cost squeeze, said Dr. Diana Pearce, director of the Center for Women’s Welfare at the University of Washington School of Social Work, who conducted the study.

“People are working just as hard and more efficiently and more productively, but it’s not showing up in wages,” Pearce said. “And their costs are going up.”

“The report shows taxes and health care costs in particular are leading the cost increases, rising by more than 70 percent each.

Dr. Diane Pearce explains the self-sufficiency standard.

This continues to add pressure to what Pearce calls the working poor — people whose jobs simply aren’t providing enough to meet basic needs.

“It’s not the lazy bunch,” said Zenobia Williams, executive director of the Maryland Community Action Partnership. “It’s hard-working Marylanders who just can’t make ends meet.”

The disconnect between incomes and costs means a lack of stability, meaning even families with two working parents are in danger of not being able to pay their bills.

They could lose their houses, their child care and their jobs.

“Movements like Occupy [Wall Street] focus on increasing income equality and wealth equality, but there’s also the issue of cost inequality,” Pearce said. “Wages have stagnated for people–especially the last few years–but costs in Maryland have continued to rise even during the recession.”

The country’s political debate is fraught with talk of tax cuts and job plans, and counties across the nation are facing the same challenges the report highlights in Maryland.

Dr. Diane Pearce explains how families living above the poverty line struggle to meet basic needs.

Out of the 37 states where the self-sufficiency standard has been calculated, Pearce said they haven’t found any place in the U.S. that hasn’t fallen victim to the growing gap between wages and cost.

In that sense, Maryland is typical of the national trend.

“It is true wages are stagnant nationwide, and these sort of good industrial jobs for low-skilled workers are basically unavailable now,” said John Ham, an economics professor at the University of Maryland, College Park.

“In terms of social programs, it’s certainly clear it’s not getting easier to be poor in America with all these budget cuts. Poor people don’t vote as much, so they’re much easier to cut than Social Security.

“And with an election looming, who votes and whom politicians pay attention to are critical pieces in this cost equation,” Ham said.

The national poverty rate stands at about 15.1 percent, meaning 46.2 million Americans are living in poverty — the highest number recorded in more than 50 years.

The federal poverty level, calculated by the federal Department of Health and Human Services, is set at $19,090 for a family of three in Maryland.

“The poverty measure is an inadequate measure of what people need to meet all their basic needs,” Pearce said. “In particular, the poverty measure hasn’t kept up with how needs have changed.”

The costs of working, including transportation and child care, were negligible when the poverty line was developed nearly half a century ago. The measure has failed to take demographic and economic changes into account, Pearce said.

And while the self-sufficiency standard is two to four times greater than the federal poverty level, Pearce said the findings might be too conservative, as they do not include expenses such as extracurricular and recreational activities, fast food and restaurant meals, and cable TV or phone service.

Despite the effects of the recession, the cost of living has seen a steady increase during the past decade. Although tax cuts and tax credits signed into law by President George W. Bush initially hid the growing disparity between wages and expenses, the gap continues to grow, Pearce said.

“Since the Great Recession, we have seen an incredible jump in people becoming eligible for and accessing food stamps and other programs,” Pearce said. “We need to not have people be demonized when they have to turn to those programs to support their families.”

State-run federal programs such as temporary cash assistance and the food supplement program are facing a growing demand.

While the state is broadening the application pool for some programs, it’s also encouraging independence from the safety net, said Pat Hines, the communication director for the Maryland Department of Human Resources.

“Welfare is a last resort. We’re here to help people with difficult times,” Hines said. “No one wants it to be a way of life. We don’t want to be in the poverty maintenance program.”

The recession has a whole new demographic trying to decipher how to apply for programs such as food stamps. And for people who find themselves in this category for the first time, public assistance is a complex beast.

“A basic part of human nature is to avoid anything that seems daunting,” Hines said, “And people are embarrassed. The last thing in their comfort zone is going to their neighbor and asking ‘How do you get public assistance?’ ”

Maryland has families of all kinds facing challenges, said Williams, at the Maryland Community Action Partnership.

“You have husbands and wives both working jobs, but it costs a tremendous amount of money to live in some of these counties,” Williams said.

The report also reveals striking differences within Maryland, from Montgomery County–more expensive than both San Francisco and New York City[–to Garrett County, where families can get by with less than half of what their suburban counterparts pay.

The range in the self-sufficiency standard for Maryland ranges from $30,291 in Garrett County to $77,933 in Montgomery County. Several suburban counties–Anne Arundel, Baltimore and Howard, among others–have seen their expenses increase by more than 60 percent.

Worst is Queen Anne’s County, where expenses have nearly doubled in the past 10 years.

While no single cause is driving the cost increases, the report shows child and health care costs in particular have risen more than 50 percent each in the last decade.

Not a single county saw their overall costs go down.

The University of Washington study did not determine how many working families have incomes below the Self-Sufficiency Standard. Census Bureau data show that roughly 1,215,591 people in Maryland — about 22 percent of the population — live in families with incomes less than 200 percent of the official federal poverty line. (For a family of four, twice the poverty line would be about $44,000.) The census data count the elderly and other categories that were not included in the self-sufficiency calculations for working families.