By Dana Amihere

GREENBELT – Built by the federal government during the Great Depression as a suburban sanctuary for low-income families, Greenbelt once again has proven a refuge through an economic crisis of historic proportions.

The walkable community of rolling green spaces and quaint homes marks its 75th anniversary this year, having glided through the housing boom and bust that led to a record number of foreclosure filings nationwide.

As one of every 25 homes in surrounding Prince George’s County faced foreclosure at the peak of the crisis in 2008 and 2009, the rate in Greenbelt was just one in 57.

Historians and economists say Greenbelt had many defenses against the turmoil. It’s a co-operative, which imposes many rules on how houses are bought and sold. It forbids rentals, so investors never destabilized neighborhoods. Its homes are small and older — not to the taste of all buyers in the overheated markets of the last decade.

“Greenbelt is a lifestyle as well as a place to live,” said Sheila Maffay-Tuthill, Greenbelt Museum education coordinator. “Some folks are into it and some folks aren’t.”

The Roosevelt administration designed and constructed Greenbelt and two other New Deal towns — one outside Cincinnati and the other near Milwaukee — to get low-income families out of the cities’ cramped and crime-ridden tenements.

Greenbelt city planners adopted a European-inspired concentric layout of 585 rental rowhouses interspersed with open spaces and footpaths. A Scandinavian company designed special furniture to ensure everything would fit comfortably in the diminutive floor plans.

Walkways were placed underneath the town’s streets and through lush greenery. Despite construction cost overruns, Eleanor Roosevelt lobbied her husband to allow completion of Greenbelt Lake, a man-made lake dug by laborers put to work in the New Deal.

More than 5,000 families applied to rent homes in Greenbelt. Those accepted couldn’t make more than $2,220 annually, about $30,000 today adjusted for inflation.

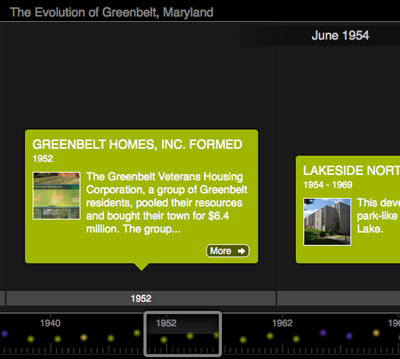

After World War II, the federal government sold the town to a corporation formed by Greenbelt residents for about $6.3 million. By then, the community had expanded to 1,580 units on 240 acres of land.

Residents reorganized as a cooperative, Greenbelt Housing, Inc., in 1957. Housing cooperatives operate as a corporation that owns real estate and acts as landlord. Residents don’t own their home outright. They own a share in the co-op, which gives them the right to occupy and sell their home — according to certain rules.

Families bought on payment plans. Those who couldn’t afford to buy in moved out, thus completing Greenbelt’s transition from working-poor to middle-class enclave.

The co-op’s organizational memo pledged to offer housing “in comfortable, pleasant surroundings at relatively low cost.”

Forty-five years later, that’s what attracted Dr. Catherine Plaisant to Greenbelt.

Plaisant, 54, a University of Maryland research scientist, sought out historic Greenbelt when she decided to downsize to a one-bedroom row house from her house in nearby University Park.

She chose Greenbelt because it was financially smarter to buy there than to rent elsewhere.

The price was so low — $50,000 — that she paid in cash.

“It was an incredible price, much better than any rental you could find,” Plaisant said. “But you have to be able to live in a close-knit community.”

Plaisant said she doesn’t find that difficult, given the perks of life in a co-op.

“I can close up for three or four months and be gone, and the co-op takes care of my home’s maintenance.”

Over the past half century, the co-op has adopted rules to protect values. Restrictions on additions, remodeling and reselling helped moderate prices and insulate the community from market shocks, said Eldon Ralph, co-op general manager.

During the recent housing boom, the practice of flipping — buying a low-end property at a cheap price, making marginal improvements and selling it quickly at an inflated price — drove up prices of some homes in Maryland and nationwide.

But that didn’t happen in Greenbelt. Co-op rules allow homes to be sold only to people who intend to live in them, and they may be resold at a profit only after two years of ownership.

“The bubble that we recently experienced all around in the Washington area, and really all over the country, didn’t really happen here because nobody could like ‘flip this house.’ I think it was something of an insulation from the bubble that was happening (in surrounding areas),” said Maffay-Tuthill.

In October 2007, at the height of the boom, the median list price for homes in Greenbelt was about $280,000, about $20,000 lower than the county, according to data from analytics service Real Estate Business Intelligence.

Some of the difference may be due to the design of the town — small homes in terms of square footage on tiny lots.

“You find that the average person isn’t going to live in a 75-year-old house with so many rules and regulations of a cooperative when you could have a lot more square footage,” said Maffay-Tuthill said.

Another reason historic Greenbelt may have been spared from the foreclosure crisis: Interested buyers must put down a minimum 10 percent deposit and get approval from the co-op. At a time when banks were giving subprime mortgages to families who couldn’t afford them with little or no money down, co-ops like Greenbelt had the power to accept or reject applicants for co-op membership based on their ability to pay the mortgage.

The difference between Greenbelt and the rest of the region may come down to the people, said Isabelle Gournay, a University of Maryland architecture and planning professor and Historic Greenbelt resident.

Americans “like to have total freedom over their property,” said Gournay. “Homeownership is sacred and we’re not exactly homeowners in the same way as most places. We’re people who don’t care so much about all the trappings of new housing and I guess that also keeps the price low.”

Melissa Major and Karl B. Hille contributed to this article.

You must be logged in to post a comment.