CUMBERLAND – Located in the middle of a small town, about as far west in Maryland as you can get, one power plant – and the technology inside it – could represent the future of coal power in America.

The AES Warrior Run power plant in Cumberland isn’t very large, with a capacity to generate about 180 megawatts of energy from coal – enough to power about 10,000 homes. What sets it apart is what it does after it’s done with that coal.

Instead of releasing all of its carbon dioxide emissions, the plant uses a chemical process to capture about 4 percent. It then takes that carbon dioxide and sells it to the food and beverage industry to store and package products.

Peter Bajc, the plant’s manager, said capturing, reusing and selling the carbon provides a small bit of revenue. And he likes the added bonus of recycling some energy, even if 4 percent doesn’t seem like a lot.

“I think it’s great that we have it and it’s great that it’s a part of the facility, but you’re right,” Bajc said. “It ain’t much.”

The plant may only remove a small portion of emissions, but its technology is important. That’s because as the government plans for more restrictions on power plants, the technology at AES Warrior Run could be a model for the future of coal energy.

Plants could use the technology on a larger scale, potentially capturing up to 95 percent of carbon emissions. But high costs and the need for more infrastructure have stalled that process.

The need for carbon capture technology comes from new Environmental Protection Agency regulations on greenhouse gas emissions from coal-fired power plants. Due to increasing worldwide greenhouse gas rates and the threat of climate change, the agency has proposed limiting emissions from new plants to about 1,100 pounds of carbon per megawatt-hour – nearly 40 percent lower than what most existing coal-fired plants emit.

If the proposal is implemented, new coal plants will need to cut greenhouse gas emissions. One way to accomplish that is by using the technology from AES Warrior Run.

The plant’s technology works by pulling out about 4 to 6 percent of greenhouse gas emissions. From there, it uses a process called “MEA absorption,” which sprays a chemical on the gas to pull out carbon dioxide.

When it’s sprayed, the MEA chemically attracts to the carbon dioxide and bonds to it, creating something Bajc calls an “enriched solution.” That solution – now a mixture of the MEA chemical and carbon dioxide, is transferred to a separate location and heated, boiling the carbon dioxide and separating it from the MEA.

The plant then cools the carbon dioxide to about minus 18 degrees, turning it into a liquid, and transports it to surrounding states to use for storing food and beverages.

George Peridas, a scientist with the National Resources Defense Council’s Climate Center, said the technology is necessary to capture carbon from larger plants.

“The technology is here today. It’s ready to be deployed,” Peridas said. “Companies are even starting to reuse this technology at a full commercial scale.”

As an example, Peridas pointed to the Boundary Dam Project, a carbon capture system being added to a coal-fired plant in Saskatchewan, Canada. By using technology similar to what’s at AES Warrior Run, but on a much larger scale and with different chemical mixes, the project is projected to capture up to 90 percent of the carbon from one unit at the plant when it launches in 2015.

What could hold back other plants from implementing similar technology, though, is cost. Plant manager Bajc said taking his plant’s technology and expanding it to capture something like 50 percent of carbon emissions could be difficult, mostly due to the new cost of powering a giant carbon capture system.

“It’s a big parasitic load to the facility. Not just from running the pumps, but the steam that it takes to make the process work,” Bajc said. “And as that system gets bigger, that makes the power plant less efficient because you have to send more steam over there and use more electricity.”

According to a 2012 report from the Congressional Budget Office, those costs could be a hindrance on new plants, potentially hiking up the cost to generate electricity by as much as 76 percent.

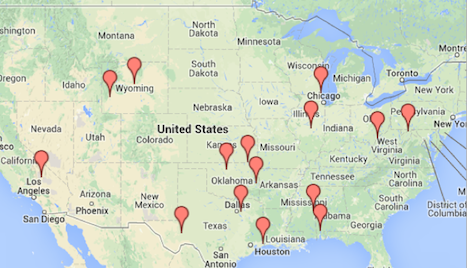

Those costs, and a lack of regulation on carbon emissions in the past, have made it so there are only about a dozen operational carbon capture projects in the United States, with only a few more scheduled to launch in the next few years.

But Edward Rubin, a professor of engineering and public policy at Carnegie Mellon University, said that even with those costs, carbon capture may soon look more appealing as more countries institute new carbon emission limits.

International committees like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have called for serious carbon reductions, and if more countries around the world comply with those recommendations, Rubin said, carbon capture may soon look like an affordable option compared to other technologies.

“That’s why we’re talking about it,” Rubin said. “Because when there aren’t any other options, if nationally you have an objective, carbon capture is actually cheap compared to other options.”

To reduce those costs even further, some scientists are looking towards new designs. In Maryland, W.R. Grace, a chemical and materials company based in Columbia, is working together with the University of South Carolina and two other companies to reach that goal using a new technology called “rapid pressure swing adsorption.”

The technology works by taking carbon emissions and flowing them over a material called a “zeolite,” which absorbs carbon dioxide while rejecting other gases, like nitrogen.

A larger-scale version of the technology is already being used at an ExxonMobil oil refinery, but the challenge for the W.R. Grace team is to make it smaller and more efficient. That will hopefully decrease costs enough to make the technology more affordable.

“All the technologies that are out there now have some limitation or the other,” said Manoj Koranne, the research and development director for W.R. Grace. “So most of the technology, there are a lot of problems with chemicals, emissions, and energy required to capture the carbon dioxide. So that kind of limits the economic feasibility.”

The project is still in development, so it’s a long way off from being used in a commercial-sized power plant. But if W.R. Grace or a company like it can develop a low-cost, high-efficiency system to capture carbon, coal-fired power plants could stay a part of the country’s energy mix for years to come.

You must be logged in to post a comment.