WASHINGTON — A British-American engraver who once formed a whirlwind friendship with Baltimore’s most influential journalist is among more than 20 artists on view in a National Gallery of Art exhibition that explores cities through prints.

“The Urban Scene: 1920-1950,” which opens Sunday, features 25 works on paper including one by Clare Leighton, who briefly lived in Baltimore, Maryland, and became fast, if fleeting, friends with legendary writer H.L. Mencken.

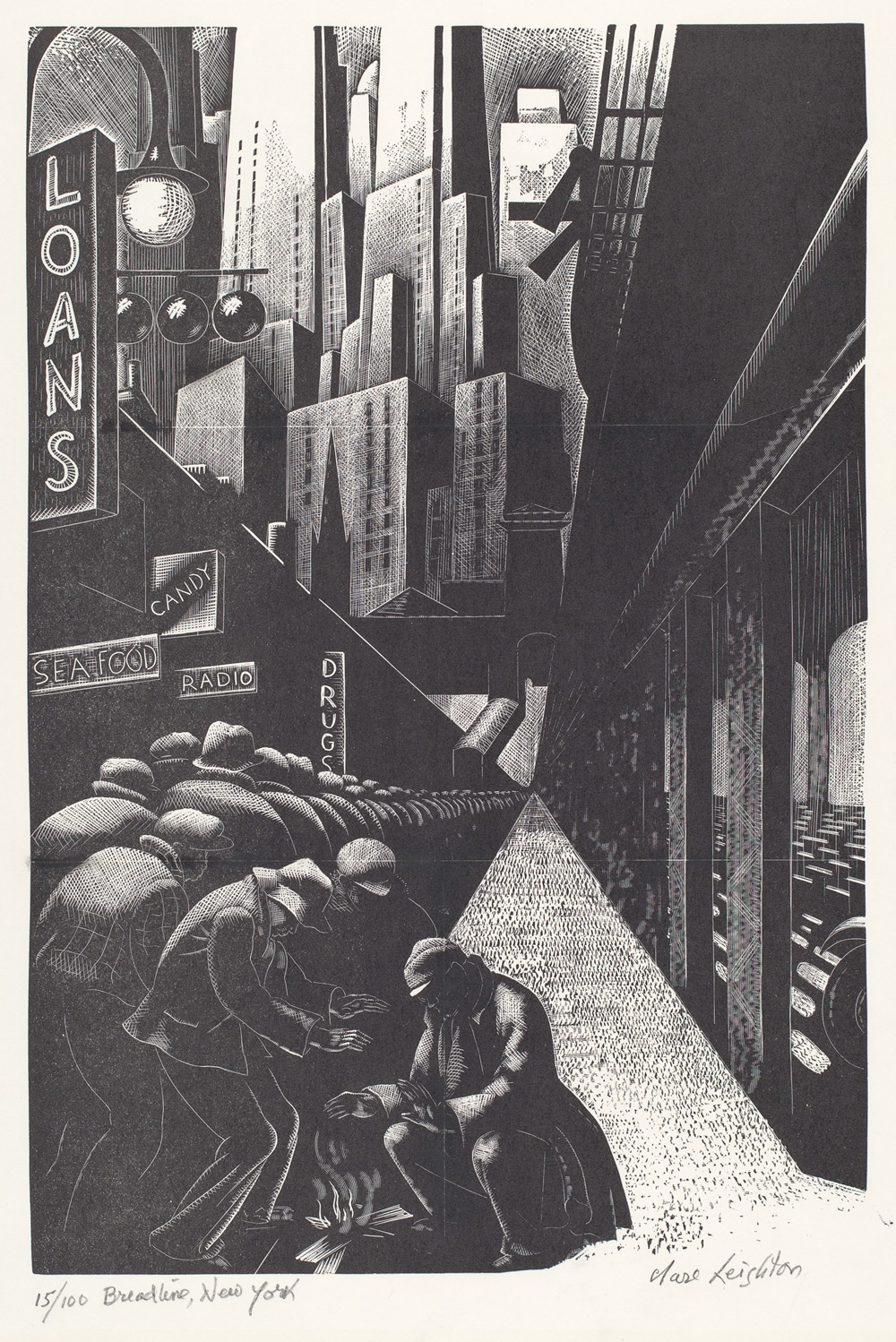

Leighton’s 1931 work, “Breadline, New York,” predates her acquaintance with Mencken by nearly a decade but shows an anti-urban sentiment, per exhibition curator Charles Ritchie, that would be rekindled by her brief, unsatisfying stay in Baltimore.

The small, black-and-white wood engraving depicts a column of monotonous, hunched-over men “that seems to sweep to infinity back to the city itself,” Ritchie said.

The men — as well as a wall of signs advertising drugs and pawn shops to their left and an elevated railway viaduct to their far right — converge in two dark triangles on a midground vanishing point. Intersecting in a lighter tone is the gleaming New York skyline above and a sliver of lit sidewalk paralleling the breadline below.

At its base, disheveled men gather for warmth over a small fire while the last vestige of an automobile speeds by under the “L.”

There’s a tension, Ritchie said at a Wednesday preview, “between the power and the possibility and the hope of the city, and yet the masses cannot be fed.”

Leighton’s attitudes about New York, expressed in “Breadline,” would return later in life when she recounted her time in Baltimore.

“Two years in Baltimore convinced me that I did not belong to the American city,” she wrote in a 1947 article Ritchie provided.

One bright spot, though, was a quick-blooming friendship with one of the city’s brightest native sons, The Baltimore Sun’s H.L. Mencken.

Mencken was a prominent reporter, linguist and social critic, and his Hollins Street home is now a national historic landmark.

When Leighton first met Mencken in 1939, their inaugural lunch date at the Hotel Belvedere lasted for nearly four hours, preeminent Mencken biographer Marion Rodgers wrote in an email.

Their friendship blossomed, Rodgers wrote, and Leighton soon met two or three times weekly with Mencken, the “Sage of Baltimore,” according to a 1956 letter Leighton wrote to publisher Alfred A. Knopf that Rodgers provided.

Soon, Mencken’s circle made hay of his “ravishing blonde at the Belvedere,” Rodgers wrote, and Leighton faced questions over the genre of her budding relationship with the man more than 17 years her senior.

The pair insisted it was just a roguish friendship, Rodgers wrote, but the pressure was enough to move their regular lunches to restaurants like Marconi’s or Haussner’s that were already on their way to becoming Baltimore institutions.

However, “their friendship was circumspect,” Rodgers wrote, and it wouldn’t last. Leighton moved to North Carolina in 1941, leaving Mencken “resentful and sad,” according to a Leighton letter Rodgers referenced.

Leighton would find a new artistic groove there, and her 1947 remarks as well as “Breadline,” make clear her views on city life and Baltimore proper. But while she dropped out of contact with Mencken, she considered him an important friend in writings to others for the rest of her life.

“I look back to my friendship with him as one of the richest experiences of my life,” Leighton wrote to Knopf in the 1956 letter.

Leighton’s sole work in “The Urban Scene” joins prints from other artists including Louis Lozowick, a Russian-American artist who was prominent in Precisionism, the first modern art movement to originate in the U.S., and others.

Made up almost fully from acquisitions since 2000, the 25-work show features many artists often overlooked by the art historical discourse, Judith Brodie, the National Gallery’s head of American and modern prints and drawings, said at the preview.

“The exhibition offers a corrective of sorts,” Brodie said. “It counters the view that museums like the National Gallery focus only on canonical artists.”

“[Ritchie] has searched through our boxes and he has unearthed artists who … are hardly household names,” she said. “The title of the exhibition, in fact, could also have been, ‘The Urban Scene: Artists You’ve Probably Never Heard Of — But Should Have.’”

“The Urban Scene: 1920-1950” runs at the National Gallery of Art through Aug. 6

You must be logged in to post a comment.