Dangerous Reporting: A series of profiles about foreign journalists imprisoned, in hiding, or silenced by courts for reporting on the most sensitive subjects in their countries

By CANDICE SPECTOR

Capital News Service

COLLEGE PARK, Maryland – When her son didn’t show up for his scheduled visit, Stanislav Aseyev’s mother went to his apartment in war-torn Donetsk, Ukraine, and found the door kicked in, his belongings scattered and the young reporter and his laptop missing, a former Ukrainian lawmaker in touch with his family told Capital News Service.

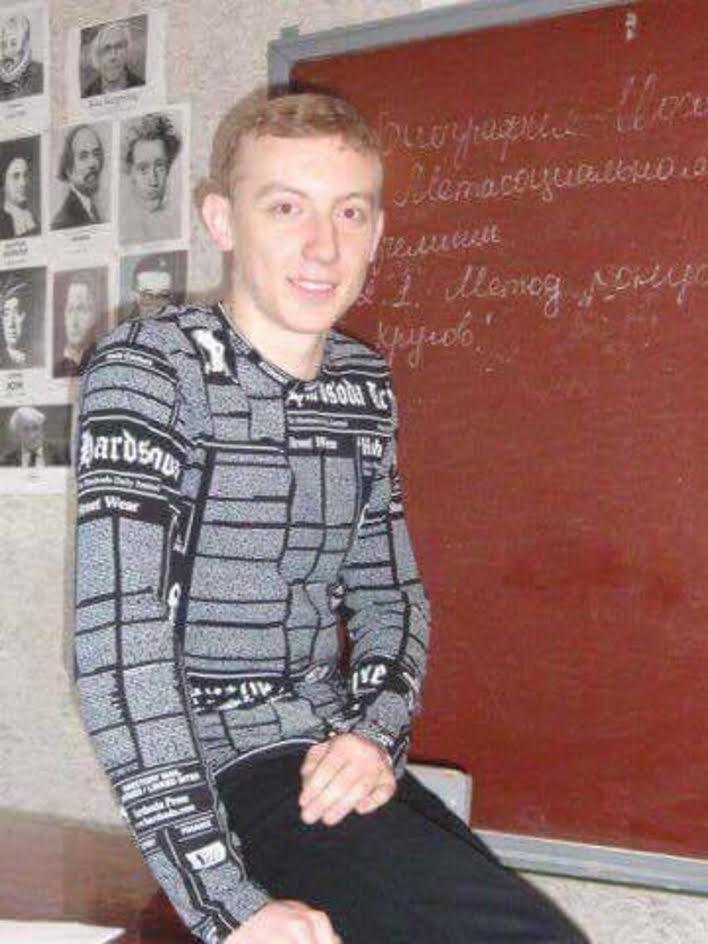

Aseyev, 28, was one of the few reporters on the ground covering the conflict in eastern Ukraine. For safety reasons he wrote under a pseudonym, Stanislav Vasin.

At the time of his disappearance on June 3, Aseyev was reporting for the U.S.-funded Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty’s (RFERL) Ukrainian Service and various Ukrainian publications.

For more than seven months, Aseyev has been imprisoned by the Donetsk State Security Ministry (MGB), the group handling intelligence and security for the Russia-backed separatists who control the eastern Donbas region in Ukraine, the Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR).

Ukrainian and RFERL officials say the authorities detained him for his reporting on daily life in Donetsk. His most notable work revealed the names and ranks of the DNR’s top five leaders.

Aseyev also exposed the lack of water supply for civilians and publicized photos that proved Russia had occupied the region, which the Russian government repeatedly denied.

The former deputy from the Donetsk region, Yegor Firsov, who is in contact with Aseyev’s family and girlfriend, said they understood immediately that his disappearance was not a robbery gone wrong.

“There were expensive things in his flat, but only his laptop was missing,” Firsov told CNS. “We realized quickly that he was arrested.”

Firsov said Aseyev’s Facebook page was open and online after he had gone missing, leading him and the journalist’s mother to believe his captors were rummaging through his online accounts after he was detained.

The journalist was held incommunicado for more than a month, according to a report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. His mother was not formally notified of his detention for nearly seven weeks.

Aseyev is one of two journalists known to be imprisoned in the Russian-occupied Donbas region. Seven journalists have been killed in Ukraine since 2014, according to Reporters Without Borders, a media advocacy group.

Aseyev has been charged with treason and espionage. He faces 14 years in the separatist prison.

The journalist is on the list of prisoners the militants are willing to exchange, Ukraine’s representative in the Tripartite Contact Group, Iryna Gerashchenko, said in a statement to Radio Liberty.

A prisoner exchange involving 73 Ukrainians and more than 200 separatists took place Dec 27, but Aseyev was not included in the swap.

Aseyev is being held in the basement of the old Izolyatsia factory in Donetsk, according to Igor Kozlovsky, who was freed in the exchange.

Ukraine’s war

Since 2014, pro-Ukrainian factions have been at war against the Russia-backed separatists in the eastern part of the country.

The eastern cities of Donetsk and Luhansk, self-proclaimed breakaway regions governed by the DNR and Luhansk People’s Republic, seek independence from Ukraine. The Ukraine government deems them to be terrorist groups. They are notorious for their mistreatment of journalists, according to human rights groups.

After Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych declined to sign an agreement to join the European Union, Ukrainians who supported becoming closer to western Europe and those who wanted a closer relationship with Russia began to clash.

The Russian government had offered Yanukovych $15 billion worth of Ukrainian Eurobonds and price cuts on Russian state-controlled resources, like gas, to kill the deal, according to news reports at the time.

The United States backs the Ukrainian government and continues to provide aid in the form of money and intelligence.

Debates have been ongoing about whether the United States should provide lethal arms to pro-Ukrainian troops. Many analysts believed it was not likely to happen, according to Arizona State University international conflict expert Braden Allenby, “because then you would have a conventional conflict on the border of a relatively nuclear state – that state being Russia.”

But in mid-December the Trump administration approved the largest U.S. commercial sale of lethal defensive weapons to Ukraine since 2014. The sale was worth $41.5 million.

Since the beginning of the conflict in April 2014, the war has displaced more than 1 million citizens, injured at least 24,000 people and killed some 10,000 – one-quarter of them civilians, according to a May 2017 United Nations report.

Media in the middle

Both sides have accused the media of misrepresenting the facts.

One militant, in an interview with CNS, denied that separatist officials treat journalists poorly and defended their apprehension of the media.

“The DNR and LNR aren’t violent toward journalists,” Bret Roberts, a British citizen, said in an interview. “They are understandably nervous around people going to and from places.”

Aseyev received threats to his Facebook page from separatist leaders saying his reports were “endangering innocent people.” A man named Sidor Fedorov issued Aseyev a warning on Feb. 3: “count your days to the end, kid,” “it is just a matter of time, my little patriot,” and “you don’t have long to live.”

Both the government of Ukraine and the separatists have deported and banned foreign reporters and maintain media blacklists to limit journalists’ access to the conflict, according to various media advocacy groups.

As a result, the Donbas has become a “black box,” said British journalist Jack Losh, who reported in the separatist-controlled region of Ukraine for the Washington Post and VICE.

“It’s bloody frustrating,” Losh said. “There are so many stories that need reporting, but you just can’t now.”

Losh described one of his confrontations. He was summoned to the DNR’s Ministry of Information and given “a big grilling by a Finnish (man) who really believed in the cause.”

“The conversation was designed to intimidate me,” he said.

Losh said journalists are captured and held in various places. “It could be in a basement, an office, a dog kennel, in a factory, or in conventional normal jails. Anything goes,” he said.

A 2016 annual report by the Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine detailed instances of mistreatment in what they called “unofficial places of detention,” such as “basements, sewage wells, garages and industrial enterprises.”

Days in prison

Since his capture, Aseyev has spent his days reading books, writing, playing sports, jogging and going on walks, according to a letter he sent to his family.

“Everything’s all right,” he wrote. “Psychologically, I’m not losing my mind. I’m staying active. There is not much space, but I have a lot of time to myself.”

Aseyev wrote that he was aware of the risks involved in his work. “I always knew one day handcuffs could snap shut,” he wrote, “so I was kind of ready for that…”

His only regret, he wrote to his family, is “forcing you to go through all this.”

Aseyev is now mentioned regularly in a song on RFERL’s special eastern Ukraine radio project, an effort to bring attention to his case, according to the director of RFERL’s Ukrainian Service, Maryana Drach.

“We have a special jingle about him, saying that we remember (him) and that he is one of our authors,” Drach said.

The song, translated from Ukrainian, says in part, “If something will happen in occupied Donetsk now, Ukraine and the world might not find out about that. There are very few professional journalists who are still working in the uncontrolled territories… It is dangerous to live without journalists. Stanislav Vasin must be released.”