BALTIMORE — In his West Baltimore barbershop, Troy Staton for years has been listening to his customers’ problems and helping their families with everything from food and diapers to suggestions they see a doctor.

In East Baltimore, Wesley Hawkins, who says his mother died of addiction, stops every week to check in with teenagers he aims to keep in school until they get a diploma.

At Frederick Douglass High School, three students are proud of their time at City Hall, where they explained to elected officials what it’s like to grow up oppressed by trauma.

Baltimore is afflicted with problems that challenge many families: high rates of poverty, struggling schools and stubborn crime rates. A network of government agencies and venerable nonprofit organizations support residents who need help.

But the efforts to help go far beyond that. In neighborhoods across the city — in places including barbershops, schools and City Hall hearing rooms — people are working in small groups and nontraditional ways to help blunt the impact of those problems and provide ways to thrive.

Now city government has a new tool to help ease trauma. In February, the Elijah Cummings Healing City Act was signed into law. It mandates training for city employees so that they can recognize trauma in the people they encounter and then respond with help. Staton, Hawkins and the Frederick Douglass High School students all supported the measure.

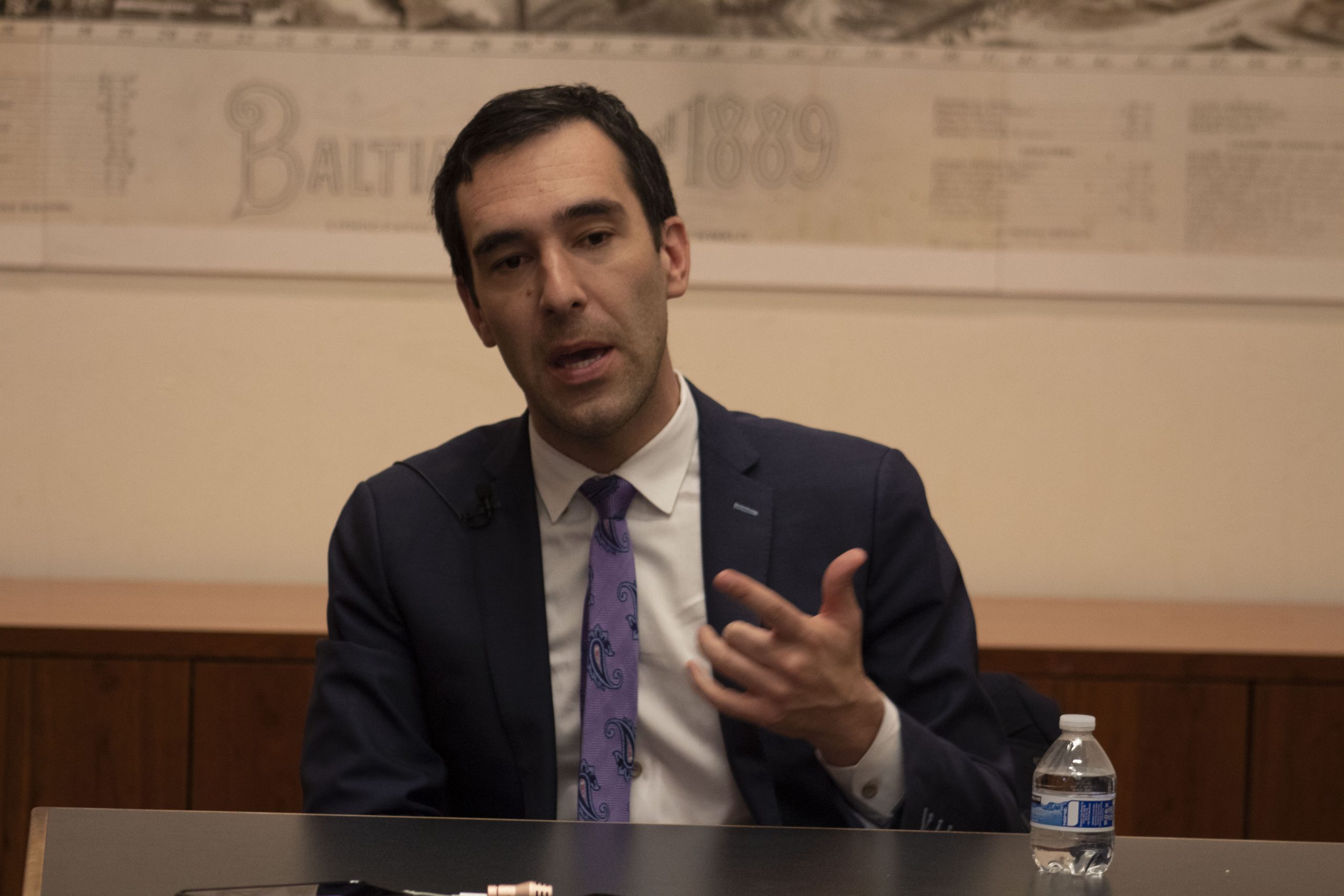

Baltimore City Councilman Zeke Cohen, a former teacher in a West Baltimore middle school, sponsored the bill. He envisions city employees from police officers to school cleaning crews and rec center coaches intervening to get help for people, especially children, who are suffering. For example, instead of writing off a depressed child, coaches at the rec center or janitors in school hallways should try to find that child help.

Decades ago, researchers began describing certain events that some children face as “adverse childhood experiences” — referred to as ACEs. The list of adverse experiences is long and includes growing up in an unstable home, having a parent in prison, living with an alcoholic parent and being the victim of neglect or abuse.

“One of the things we know about trauma: It changes the way we view the world,” said Michael Sinclair, associate professor at the Morgan State University School of Social Work.

The impact of trauma may shape a child’s life, increasing the risk for everything from depression to teen pregnancy, from failure to graduate to problems settling into stable relationships, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

To allow people to deal with trauma and thrive, policies must change, “a paradigm shift,” Cohen said in an interview. A “trauma-responsive” approach can change Baltimore’s future.

“We are a city with an enormous amount of pain,” Cohen said. “But we also have an enormous amount of potential to heal.”

And community leaders will continue to work alongside government to find ways to help support neighbors dealing with trauma.

“If we don’t take a chance,” said Wesley Hawkins, who counsels teenagers, “then what?”

At City Hall, Cohen said, “The sense of urgency to do this work could not be higher.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.