ANNAPOLIS, Md. — Maryland police officers who are dealing with stressors — such as family issues, substance abuse or mass protests — will have access to confidential mental health aid under a bill progressing in the state Legislature.

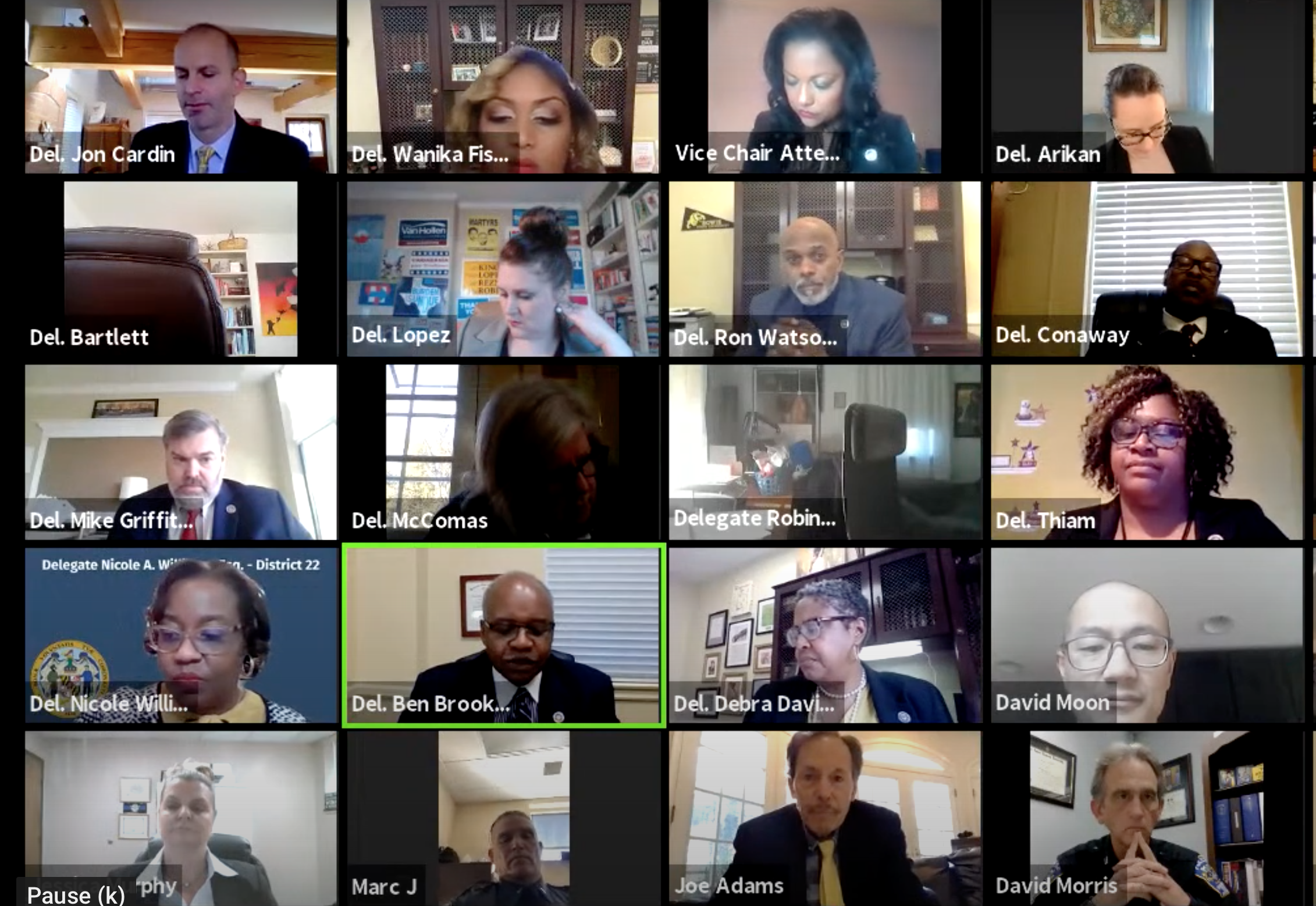

The Police Officers Mental Health Employee Assistance Program, sponsored by Del. Benjamin Brooks, D-Baltimore County, and Sen. Mary Washington, D-Baltimore, would require each law enforcement agency to provide its officers with access to an employee assistance or mental health program at a minimal cost to the officer.

These employee assistance programs include confidential counseling services, crisis counseling, stress management counseling and peer support services for police officers.

“One in four police officers have thought about committing suicide at one point in their career,” Brooks told Capital News Service.

An important component of these employee assistance programs focuses on protecting police officers’ mental health during periods of public demonstration and unrest.

Looking out for police officers’ mental health during those periods is now more prevalent than ever, as protests have increased throughout the United States over the past year.

Currently, an Employee Assistance Program, administered through the Department of Budget and Management, is only offered to state employees.

However, this bill would mandate similar programs in every law enforcement agency throughout Maryland, allowing police officers in local municipalities around the state to receive mental health assistance if necessary.

“It doesn’t matter whether your police department is 25 people or 400 people,” Washington told Capital News Service.

While providing police officers mental health resources is a key priority, so is ensuring the confidentiality that comes along with accepting those services.

“Confidentiality is the biggest thing with mental health,” Dr. Annette Hanson, joint legislative committee chair for the Maryland Psychiatric Society and Washington Psychiatric Society, told Capital News Service.

Confidentiality is vital when it comes to mental health because it’s become such a highly stigmatized issue — particularly in fields like the military and law enforcement.

Under this bill, police officers would receive the help they need, and avoid potential repercussions from the department or fellow officers.

“It makes our law enforcement officers feel that they’re more than a badge, that they’re human,” Lt. Marc Junkerman of the Harford County Sheriff’s Office, said in support of HB0088 at a Tuesday hearing.

Before initially introducing the bill last year, Brooks began to conduct research as he came across some information about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

A Vietnam War veteran, Brooks was aware of PTSD, but he began learning more about the startling statistics related to police officers and mental health struggles.

In 2019, 228 police officers died by suicide compared to 172 officers the year before, according to Blue H.E.L.P. an organization dedicated to reducing the stigma around mental health.

Not only do these mental health challenges affect the police officers, but their family members can also be greatly affected as well.

Last year, a police officer’s wife approached Washington and explained the challenges that family members deal with when their partner is experiencing mental health issues.

Some of these challenges can include the officers exhibiting a change in behavior — possibly turning violent or turning to alcohol and other sources as coping mechanisms for the traumas they’ve faced.

To mitigate some of these familial challenges, under this program family members can report to the employee assistance program if they feel their spouse or parent is in need of mental health assistance.

Brooks and Washington initially introduced this bill last year, when it passed through the House unanimously but halted in the Senate because the 2020 session ended early due to the coronavirus pandemic.

However, Washington is still confident that the bill will pass this year given the insights they’ve had over the previous year.

No official date has been scheduled for the bill to be voted on.

“When the officer goes to my door or my neighbor’s door, I just want them to be whole,” Brooks said.