Natasza Bock-Singleton could smell it from where she was sitting in her home office in the basement. She could hear it too — a gurgling sound, coming from the bathroom. She got up to find out what was going on.

It was “this kind of geyser of human poo that was coming out of the toilet,” Bock-Singleton said.

She grabbed galoshes and gloves from her mudroom, threw them on and used a Shop-Vac to divert the sewage that had built up out to her backyard.

“If you can imagine walking into a public restroom where somebody hasn’t flushed the toilet, multiply that by 100, that’s what it was like,” Bock-Singleton said.

The flood of sewage came shortly after a heavy rain. She, her husband and their three kids then set to work cleaning up the remains of sewage, bits of toilet paper, condoms and other debris that spilled into their home.

“It was all hands on deck to kind of get everything clean,” Bock-Singleton said.

After having to throw away her contaminated Shop-Vac, ceramic tiles and replacing the bathroom drywall, she invested $30,000 into installing backflow prevention valves into her home’s lateral sewer line to prevent future backups.

It was the first time her home had flooded with sewage.

Thousands of Baltimore residents report sewer backups into their homes each year. In an effort to address the problem, the city launched a reimbursement program in April 2018. The program, run by the Department of Public Works (DPW), allows residents to request reimbursement from the city for sewer backup cleaning costs, up to $5,000 for a given backup.

Sewage backups reported to 311 in 2020, over time

Source: Baltimore’s open data portal. (Matt McDonald/Capital News Service)

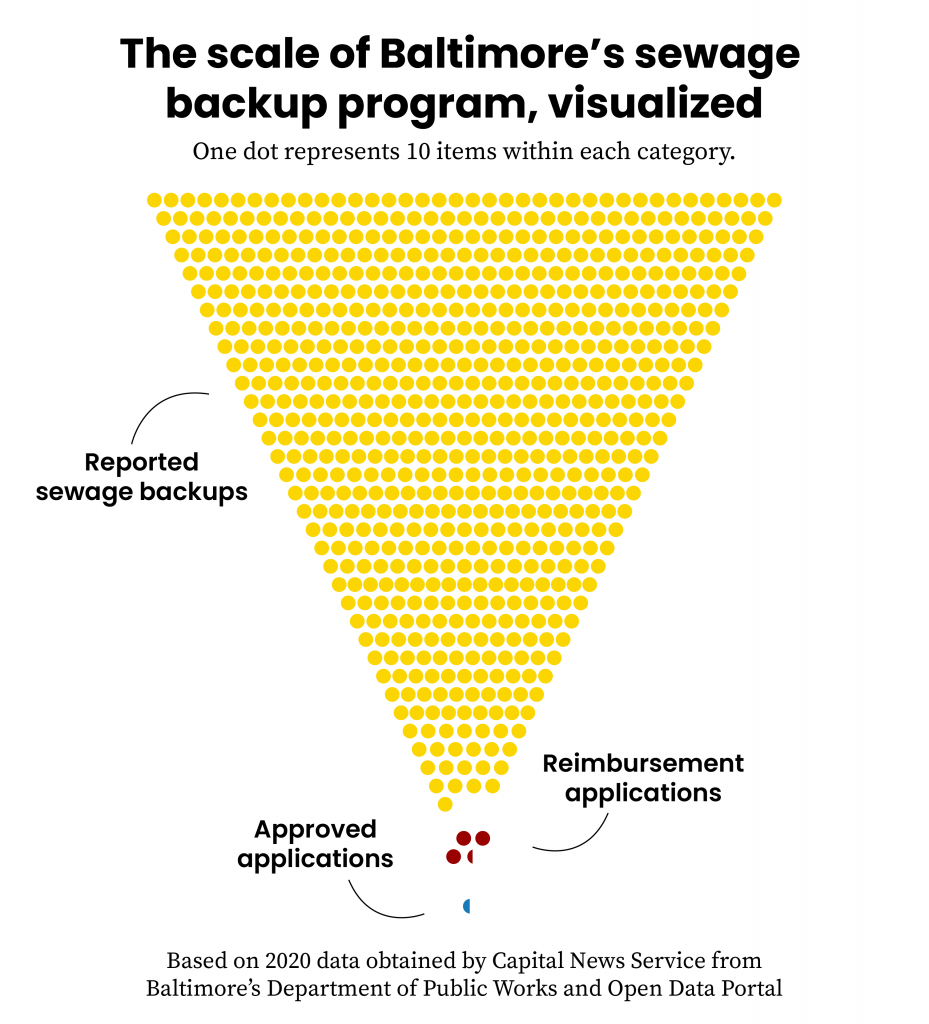

Yet few apply to this program, and only a small fraction of those who do see a payment from the city. The eligibility requirements of the program result in the majority of applications being rejected, a Capital News Service analysis found.

Since the program began in April 2018, only 120 requests for reimbursement have been filed by residents as of March 24, 2021, according to data obtained by CNS through a Public Information Act request. Of those requests, only 19 were ever approved.

During the same time period, the city received more than 18,700 reports to its 311 service related to sewage backups in homes, according to records obtained by CNS through the city’s public data portal. Residents reported more than 7,000 backups in 2020 alone.

When asked about the low number of applicants to the program, Yosef Kebede, the DPW’s acting head of Water and Wastewater, admitted the city’s outreach efforts weren’t robust when the program began in 2018.

“I can see why that raises eyebrows,” Kebede said.

He said communication has since improved. For example, he said, the DPW sends out reminders about the program on social media when heavy rains are forecasted.

Bock-Singleton’s home backed up again later in 2018 after two inches of rainfall pushed sewage past the backflow preventers. This time, she applied for reimbursement from the city. She was rejected, she said, because the city found a stick in her sewer line.

The reimbursement program only covers cleanup costs if DPW investigators determine that the sole cause of the backup is a wet weather event. Though it had rained more than two inches the day before Bock-Singleton’s backup, the stick in the line disqualified her.

Aging infrastructure

Sewage backups in homes are part of a larger problem: Baltimore’s sewer infrastructure is old and overburdened.

The city’s sewer system is more than a century old. The pipes are in places cracked, misaligned, or otherwise faulty. Those faults allow storm and groundwater to flood into the sewer lines, leading to sewage backups.

Other issues can also cause or contribute to overflows, including blockages caused by tree roots or products improperly flushed down the toilet, such as baby wipes and menstrual products.

“You quickly reach a threshold where the system is overwhelmed,” said Marccus Hendricks, the director of the Stormwater Infrastructure Resilience and Justice Lab at the University of Maryland.

It is a combination of “vulnerable infrastructure systems, increasing development, and, because of climate change, more frequent and intense wet weather events that are coming to a head that are causing these overflows and backups, not only in Baltimore, but in cities across the country,” he said.

Baltimore’s sewer system has long dumped human waste in places it doesn’t belong. Relief valves built decades ago have directed sewage overflows into rivers and tributaries leading into the Chesapeake Bay. The city reported overflows totaling nearly 50 million gallons of sewage mixed with water in 2020 alone, almost all of it into the Jones Falls.

The city has poured over $830 million into stopping overflows and improving sewer infrastructure since an agreement it struck in 2002 with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the Department of Justice and the Maryland Department of the Environment. That agreement, called a consent decree, headed off the threat of a lawsuit from the agencies, which alleged the city was violating the Clean Water Act by polluting waterways.

As the city closed relief valves, sewage backups in homes began to happen frequently. There were 622 backups in 2004, according to The Baltimore Sun. There were more than 5,000 backups each year in the decade leading up to 2015.

The city’s response

The city created the Expedited Reimbursement Program as part of a modified consent decree negotiated after the city failed to complete its sewer overhaul by the 2015 deadline.

The program only covers clean-up, disinfection and disposal costs related to “capacity-related wet weather events,” defined on the DPW website as when at least a quarter inch of precipitation within 24 hours causes “sewer lines to surcharge or overflow.”

Homeowners and tenants can apply for reimbursement by filling out an application online, by email, or by mail. Applicants must provide supporting documentation, including copies of receipts for cleaning and disinfection costs. Residents whose applications are rejected can still file a general liability claim for property damage to the city’s law department.

The city denied about 84% of applications it has received since the program’s April 2018 start date — 101 out of the 120 submitted by residents. (Four applications were rejected because they related to backups that had occurred before the program began.) The most recent application in the data reviewed by CNS was received in February 2021.

About 23% were denied because they did not report the sewage backup within 24 hours of it occurring, a requirement until July of 2020. Even after lifting the 24-hour reporting requirement, the city went on to reject more than 80% of applications.

The city has paid out less than $20,000 to applicants since the reimbursement program began, according to the program data. The consent decree set the annual funding for reimbursements to “at least $2 million.”

Asked why there are so few payouts, Kebede said that the bureau’s budget, which is funded by resident water bills, necessitates a limit on how the funds are used.

“The denials are based on procedures and protocols that we have to follow and be consistent with,” he said. “Nobody feels good about that.”

City Councilman Kristerfer Burnett sponsored a bill that would require the DPW to study the expedited reimbursement program and a related program and report on whether it would be feasible to allow the programs to cover all sewage backups, not just ones caused by wet weather.

Burnett said that his constituents experience backups caused by both wet weather and dry weather. The programs also have issues with equity, he said; cleanup costs for backups hurt those that are struggling with income the hardest.

“There’s just some criteria [in the programs] that I think still doesn’t go far enough to serve our citizens,” he said.

Families struggle with sewer backups

The city rejected claims if investigators found an obstruction such as rags, grease, debris or roots in the sewer line. In such cases, a wet weather overload was ruled out — even if it had rained right before sewage backup.

That happened to Dorothy Conaway, a retired educator who has lived in her home on Belvieu Avenue for nearly 47 years. During a phone interview, she read from the denial letter she received from the city in response to her reimbursement application for a July 25, 2018 backup.

“The agency investigators responded to your incident and determined that the incident was not caused by surcharging in the sewer collection system due to wet weather, but caused by rags and debris that were removed from the sanitary sewer main line,” the letter said. “And it says ‘see attachments,’ which I never got,” Conaway added.

It had deluged more than four inches in the city the day before on July 24, the second wettest day on record.

On May 27, 2018, the same day torrential rains pelted down across the state of Maryland, flooding the streets of Ellicott City, Rachel and Nicky Mutinda’s West Baltimore home filled with sludge from the sewers.

The city found that the sewer lines had surcharged, reimbursing the Mutindas for $1,000 of the $2,500 they had requested because insurance had covered part of the costs, according to the program data, making them one of 19 households approved for reimbursement.

Rachel Mutinda said she thinks that she and her husband found out about the city’s reimbursement program from an article shortly after the backup.

“It is not obvious where to find this information,” Nicky Mutinda said.

Rachel Mutinda said following an application all the way through to success took a combination of persistence, internet savvy and the freedom to be able to follow up with the city during the workday.

“Not everybody has that ability to have that persistence,” she said.

Exposure to human waste can be very dangerous; it can carry parasites, viruses and bacteria, Christopher Heaney, an environmental epidemiologist and associate professor at Johns Hopkins University, told city councilmembers at a hearing on sewage backups in 2019.

And the moisture from sewage backups can lead to the growth of mold, fungi and other harmful microorganisms, Heaney added — “a huge concern for individuals who have respiratory health problems.”

Leah Brown worries about the health of Tierney, her six-year-old daughter, who has asthma.

Their home has been inundated with sewage multiple times, seeping up from the basement shower drain and into the home Brown shares with her husband, Tony Murray, her daughter, and two teenage sons in Howard Park. After one such occasion, a contractor found black mold as they cut away at the basement walls.

There was “so much” of it, Brown said. “That part was really scary.”

On March 23 this year, Mayor Brandon Scott and the DPW announced a one-year pilot program that would have the city contract with third-party cleanup services directly and send them to the people experiencing backups. With the reimbursement program, residents need to pay for cleanup and then request reimbursement. For the new Sewage Onsite Support (S.O.S.) Cleanup Program, the city pays for third-party cleanup services and sends them to the people reporting backups — if they qualify. (The S.O.S. program does not replace the reimbursement program; residents can choose between the two.)

Once investigators determine a resident’s backup was caused by wet weather, they’ll ask if the resident would like the city to dispatch a cleaning service to their home. Kebede said he hopes the S.O.S. program’s simplified process will let it reach more residents. He said that the program had so far helped five people, at the time of the May 5 interview.

Brown’s home filled with sewage again the day after the Mayor’s announcement. When she called 311, the city didn’t inform her about the existence of either cleanup program, Brown said. Instead, she heard about them from a member of Clean Water Action, an advocacy group.

Brown’s entire house smelled of excrement. Tierney couldn’t be there anymore. Brown took her to her neighbor to watch after her. One of Brown’s sons tried to help clean but grew so nauseous he nearly vomited. Her other son, Chandler, spent his sixteenth birthday cleaning up sewage in the basement bathroom.

It rained more than one and a half inches the day of the backup, breaking a record for rainfall on March 24. But when Brown spoke with city officials about the S.O.S. program, she was told she didn’t qualify — DPW investigators had found roots interfering with the main sewer line and the pipe leading to her house.

Brown said it seemed to her like the city is dodging accountability for its century-old sewer infrastructure. Her basement has never backed up with sewage on a sunny day, she said — only when it rains — and yet the city blamed roots.

Brown was hopeful about the new cleanup program when she learned of it. But she expects most people will end up with experiences like hers.

“On paper, if I’m sitting here looking at it, I’m like, ‘Oh, this looks great,’” she said. “But then once you start to read the fine print, that’s when you start saying, ‘Oh, it really doesn’t help me.’”

You must be logged in to post a comment.