WASHINGTON — William Lacy Clay Jr. remembers being 12-years-old and standing beside his father launching his campaign bid one day after the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in the spring of 1968.

It was a historic race for the House: William Lacy Clay Sr. became Missouri’s first Black representative elected to Congress, in part because of redistricting that gave him a seat containing the state’s largest concentration of Black voters.

Shortly after the monumental victory, the congressman-elect and his family — his wife, Carol, Clay Jr. and daughters Vicki and Michelle — moved to Washington.

Clay Jr. attended Montgomery County public schools in Silver Spring, Maryland, later enrolling at the University of Maryland, College Park. He took a full-time job where his father, the new congressman, worked.

“My assignment was a doorman in the U.S. House of Representatives, which allowed me to see my dad working Capitol Hill up close, and learning the legislative process,” Clay Jr. told Capital News Service.

In 1971, Clay Sr. joined 12 other Black House members to create the Congressional Black Caucus, six years after the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed.

The caucus is celebrating its 50th anniversary and remains in the forefront of struggles over civil rights and voting rights. In this Congress, the caucus, now grown to 57 members, has been battling to enact legislation intended to counter voter suppression efforts championed by Republicans in Congress and state legislatures.

The Congressional Black Caucus played an instrumental role in propelling the final passage of President Joe Biden’s bipartisan infrastructure bill, a $1.2 trillion spending package that will funnel federal dollars to bridges, highways, airports, water projects and expanded broadband services, among other projects.

“We believed that most members would want to go back home and say what they delivered,” Caucus Chair Joyce Beatty, D-Ohio, said on MSNBC’s “Morning Joe” on Nov. 8.

With six caucus members serving as chairs of committees, the group also has influenced the shaping of the so-called Build Back Better bill, a nearly $2 trillion investment in social programs Biden also is pressing Congress to pass. The measure passed the House on Friday.

“It’s transformational… We have had our fingerprints and footprints are all over this legislation,” Beatty said.

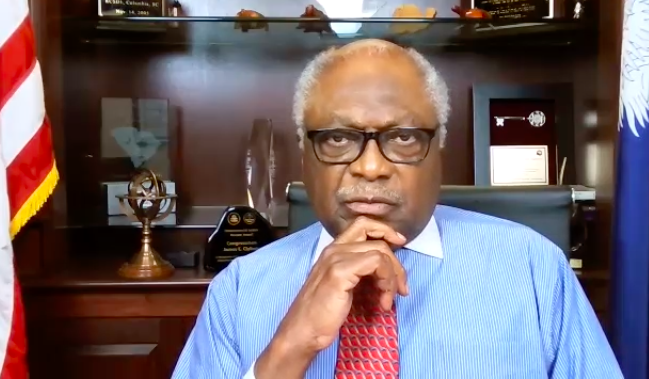

Since its founding, the caucus has had relationships with every president — some better than others. As for Donald Trump, there essentially was no relationship. He never officially met with the entire caucus, partly because he “demonstrated significant disrespect for the caucus,” House Majority Whip James Clyburn, D-South Carolina, said.

“I don’t know any better member to ever serve in the Congress as more lionized than John Lewis, but the former president insulted him in a way that is almost unbelievable,” Clyburn told CNS.

Lewis, a Democrat who represented Georgia’s 5th District and was a civil rights icon, died last year. Asked about Lewis, Trump said in an interview with Axios on HBO that the Georgian “chose not to come to my inauguration,” later saying “nobody has done more for Black Americans than I have.”

Like father, like son

William Lacy Clay Sr. was at the heart of the civil rights movement as an alderman in St. Louis, Missouri. He became a supporter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and was jailed for 112 days during the 1963 Jefferson Bank demonstrations, a series of civil protests aimed at addressing racial discrimination in workplaces.

Twenty years later, Clay Sr. and his caucus colleagues led the movement to make King’s birthday a federally-recognized holiday.

Clay is known for coining the phrase “just permanent interests,” his son said, “and it is the model for the Congressional Black Caucus. In politics, Black people have no permanent friends, no permanent enemies, just permanent interests.”

In 1992, Clay Sr. authored Just Permanent Interests: Black Americans in Congress 1870-1991. The book is “treated like the Bible of Black politics,” his son said.

After graduating from college, Clay Jr. got accepted into the Howard University School of Law, but was only there about a month before politics beckoned.

Nathaniel J. “Nat” Rivers, a member of Missouri’s state Legislature and close friend of Clay Jr.’s father, was resigning in 1983. Then 27, Clay Jr. entered a special election and won. He served for 17 years in both houses of the state legislature.

Clay Sr. announced his retirement in 2000, opening up an opportunity for his son to run and ultimately succeed him after fending off a competitive bid for Missouri’s 1st Congressional District.

The younger Clay was sworn in with the rest of the 107th Congress in 2001. Carol W. Clay, his daughter, stood to one side, while his father, Clay Sr., stood on the other.

“It was a recreation of what I did in January of 1969, when my dad was first sworn in,” Clay Jr. remembered.

He said his new job wasn’t a drastic adjustment.

Clay Jr. already knew many of the Black lawmakers from his younger days serving as a doorkeeper: Georgia’s Lewis, Reps. Charles Rangel, D-New York, Ronald Vernie Dellums, D-California, and Louis Stokes, D-Ohio, a former neighbor in Silver Spring whose lawn he used to cut.

“My job description was to know all 435 members of Congress by name and state and to inform them on what the votes were, and for me to come back 17 years later, as a member, it was just the thrill of my life,” Clay Jr. explained.

He also made new friends among fresh faces in the caucus, too.

Clay Jr. said he and then-Sen. Barack Obama, a junior Democrat from Illinois, “quickly became close friends and worked on legislation together.” Clay and Obama spearheaded legislation to fund the construction of the Stan Musial Veterans Memorial Bridge, which connects St. Louis, Missouri, to St. Clair County, Illinois.

Neither Clay nor his father believed they would ever witness the election of a Black president during their lifetimes. But in 2009, Clay Jr. was on the inauguration platform on the West Front of the United States Capitol watching his friend Obama take the oath of office as president.

The seemingly impossible happened once again in 2020, when a CBC alumna, Sen. Kamala Harris, D-California, battled her way to the vice presidency, breaking racial and gender barriers in the process.

“It’s amazing the progress that has been made through the CBC over fifty years,” Clay Jr. added.

After serving two decades, he lost his seat in a contentious primary in 2020 against Cori Bush, a nurse and Black Lives Matter activist.

Still permanent interests: 50 years later

Harris acknowledged her ties to the caucus while speaking at the 10th anniversary of the MLK Memorial alongside President Joe Biden in late October.

“Chairwoman Joyce Beatty and my — I will call you, still, my colleagues at the Congressional Black Caucus. Thank you all for your leadership,” Harris said at the podium while standing in front of the towering 30-foot tall white granite statue.

Rep. Barbara Lee, D-California, remembers serving as the chairwoman of the caucus during Obama’s presidency, a time when the memorial was just constructed. Lee told CNS the caucus still plays a crucial role in “fighting constantly for justice, not only for African Americans, but for the entire country.”

“Fifty years later, we’re championing many of the issues that we were championing back then,” Lee added.

The legacy built in part by Clay’s father is being expanded by the 57 Black caucus members serving in the House and Senate. They represent 27 states as well as the Virgin Islands and the District of Columbia. Sens. Cory Booker, D-New Jersey, and Raphael Warnock, D-Georgia, are only two of a total of 11 Black senators who have served since 1870.

Black representation in Congress had a brief flowering after the Civil War. In 1870, Hiram Revels, a Republican from Mississippi, became the first Black senator in U.S. history. The election the same year of Rep. Joseph Rainey, R-South Carolina, the first Black member to serve in the House, also gave hope for Black communities that sought to become a part of the political process.

Other Black lawmakers followed in their footsteps, but by the start of the 20th century, a resurgence of white racism and racial violence — buttressed by segregation, voter suppression and Jim Crow laws in the South — extinguished Black ambitions for a role in national political life.

“The people who founded the new caucus reminded me that no matter how long I stayed in Congress, or how many stories were written, I owe it to myself to talk about the original African American members of the Congress, who by 1901, had completely disappeared as a result of Jim Crow, and redistricting and gerrymandering,” Rep. Kweisi Mfume, D-Baltimore, told CNS.

Fifty years ago, the original 13 founding Black caucus members made up only two percent of the Congress. Today, the caucus is 10 percent of the Congress.

Marc Morial, president and CEO of the National Urban League, said the caucus has evolved “where it’s a far more diverse body, because its members represent mixed districts.”

“Some represent dominantly white districts, some represent predominantly Black districts,” Morial, former mayor of New Orleans, told CNS.

Not only is the CBC a representation of “Black America on Capitol Hill,” Morial said, it also serves as “the conscience of Congress.”

Parren Mitchell was Maryland’s first Black House member, representing the 7th District from 1971 until 1987.

Mfume was first elected to Congress from Maryland’s 7th District in 1986, succeeding Mitchell in the same district. He served until 1996, when he left to become president and CEO of the NAACP.

Rep. Elijah Cummings, D-Baltimore, succeeded Mfume. Cummings died in office in 2019. Mfume won a special election in May 2020 to return to the House, again representing the 7th District.

In Maryland’s 4th District, Democrat Albert Wynn served from 1993 until 2008. Democrat Donna Edwards succeeded him, serving until 2017.

Rep. Anthony Brown, D-Upper Marlboro, succeeded Edwards, and is now running for Maryland attorney general.

Mitchell, Mfume and Cummings all served at different times as chairmen of the CBC — the most chairmen to come from the same House district.

“I can simply say that caucus, and the opportunity that you get to represent issues and people beyond where you are elected from is significant, and it’s humbling,” Mfume said.

The caucus chairmanship also means wielding power — the ability to focus some attention in Washington toward the interests of Black constituents — a responsibility Mfume said he carried very seriously.

“It was an opportunity to put together a plan that would move the agenda forward,” the veteran Baltimore lawmaker said. “For me, it meant having 40 votes in your back pocket on any given day.”

Bill Clinton. Rosa Parks. Nelson Mandela. Mfume met many prominent public figures during his tenure as chairman. During the Clinton administration, Mfume recalled, he pressed caucus members not to sign off on any initiatives unless they “fell in line” with their expectations.

“That was the most rewarding aspect of my term as caucus chair, to be able to parlay votes in a way that had not been done before,” Mfume added. “But in a way now, that is sort of kind of second nature to how we operate.”

Still facing challenges

But even with 55 votes in the House, the power of the Black caucus alone has limits: the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, a bill that passed the House in 2020 and again in March, has stalled because of Senate Republican opposition.

“It’s heartbreaking for families across this country, who wanted to believe that their Congress would in fact find a way to deal with this issue of police, excessive use of force,” Mfume said. “The Senate had no stomach for it and eventually found a way to walk away from it.”

Much like the police accountability legislation, the Senate doesn’t have a stomach for addressing threats to voting rights either, advocates like Morial say.

Brown believes passing legislation like the Freedom to Vote Act and John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act are possible ways of addressing “one of the most fundamental issues” the nation faces.

“Without the right to vote and the unencumbered access to the ballot, then everything that we fight for becomes that much more difficult,” Brown told CNS.

“We shoulder a responsibility to not only champion the aspirations, the dreams, the goals and the pursuits of the Black community, and frankly, the Black diaspora,” he added. “Our work goes beyond domestic policy… to protect and defend the interests and the rights that continue to be under assault and attacked in this country, even today, in 2021.”

Reparations for slavery is an integral part of that conversation for the caucus.

Mfume remembers cosponsoring a reparations bill by former Rep. John Conyers Jr., D-Michigan. The measure was introduced consecutively for a decade and Mfume said it’s frustrating to return to Congress without any progress on that front.

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, now is sponsoring House Resolution 40, a bill aimed to establish a commission to determine possible paths forward for slavery reparations.

“If you’re going to get real reparations on behalf of the Afro-American community, there has to be a federal commitment.” Brown added. “It’s difficult for that to happen without first having a commission.”

Clyburn, another former CBC caucus chair who now serves as the Democratic majority whip, says the agenda shifts from time to time, depending on which issue “ought to be at the front of the line.”

“There are times when I think things like HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) should be at the front of the line. Other times, I think that closing the wealth gap should be at the front and closing the healthcare gap. These gaps are all there… we know they’re there,” Clyburn told CNS. “It all depends on what’s taking place in the Congress and the country as to how we ought to be prioritizing.”

Even though Rep. Eleanor Holmes Norton, D-District of Columbia, is one of the most senior members from the caucus, sharing that title with Rep. Maxine Waters, D-California, she said she still feels largely left out of the legislative process.

“Even when I came, we’re under-represented,” Norton said in an interview with CNS. “The Congressional Black Caucus took the role of Congress, men and women at large, recognizing that many African Americans were in districts where they had no hope of representation and somebody needed to speak for them.”

That was especially true for the District of Columbia, an underserved constituency, even to this today.

“We need all the help we can get,” she added. “I think the most important issue facing the Congressional Black Caucus is statehood for the District of Columbia.”

For Norton, having full voting powers representing the new “State of Washington, Douglass Commonwealth,” as House-passed bills would rename the District, could be crucial in a narrow House Democratic majority like the one now.

But prospects for getting statehood for the District through the current Senate, divided evenly between Republicans and Democrats, are very poor.

“I have all of the powers of any other member of the House except that final vote in the House of Representatives,” Norton said. “Now when we control the House by only three votes, you can see how that would matter.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.