By Joseph Antoshak

With reporting by Carlos Alfaro and Zoe Sagalow. Read the full-series, Discharging Trouble

COLLEGE PARK – Vonda Wagner and Andrew Edwards said they were kicked out of their licensed nursing homes and wound up in an unlicensed assisted living facility. Here’s how that happens in Maryland…

1. Staffing shortfalls prevent the state from adequately monitoring assisted living and nursing homes

The Office of Health Care Quality regulates nursing homes in Maryland and it doesn’t have enough people to do the job. At the end of last year, about 1 in 5 positions in the OHCQ was vacant, according to an analysis of its 2017 fiscal year budget.

The staffing shortage affects OHCQ’s monitoring of licensed assisted living homes, as well as how it keeps tabs on the network of those operating without a license. According to a state legislative budget analysis, OHCQ “has faced chronic staffing shortages over the past few years due to the combination of an increased workload, a structural deficiency in positions allotted for survey and inspection activities, and chronic vacancies among surveyor positions.”

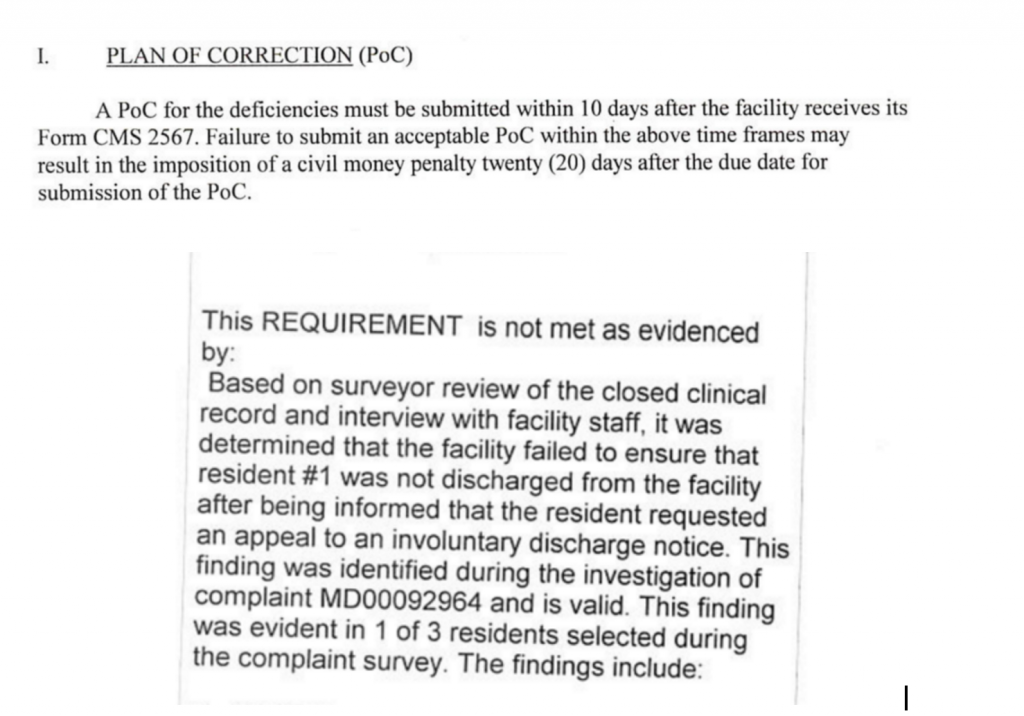

It has also affected OHCQ’s ability to monitor skilled nursing homes. Last year, it took the office 34 days on average to initiate nursing home complaint investigations, though federal regulations require that they are initiated in 10 days or fewer. That can widen the door for abuse and neglect in the discharge process and beyond.

For its part, the OHCQ said it is performing the required inspections and surveys to make sure nursing home and assisted living patients are treated properly, said Christopher Garrett, spokesman for the Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

2. Technical jargon and buried information makes researching nursing homes extremely difficult

For those looking to enter a nursing home, digging out information is no easy task. While the Medicare.gov nursing home compare tool is probably the most useful due to its one- to five-star rating system, it doesn’t guarantee a speedy research process.

“It’s not perfect, but it sure is a good starting point,” said Alice Hedt, former Maryland state long-term care ombudsman.

The problem stems from OHCQ not keeping records on all people discharged from nursing homes. It only tracks cases where residents have filed complaints.

That means that a person would have to obtain OHCQ’s annual or semi-annual surveys of the state’s nearly 230 skilled nursing facilities — which are packed with technical jargon — to find this information. This poses a potential problem for consumers, who could otherwise recognize sites with abnormally high discharge rates and steer clear of them.

The end result can be a self-perpetuating problem: Residents could unknowingly enter facilities with questionable records.

3. All this leads to a greater chance of winding up in an unlicensed assisted living facility

Nursing residents face significant problems when it comes to assisted living homes. Capital News Service has examined three cases where residents were discharged to unlicensed assisted living facilities with dangerous outcomes.

One of the ways this happens is that site managers operate both licensed and unlicensed homes at the same time and move residents to facilities unregulated by the state.

“They bring people in through the licensed facility,” said Anne Hurley, former director of Maryland Legal Aid’s Long-Term Care Assistance Project. “And then a lot of times they shuttle them to unlicensed facilities.”

Assisted living homes may network and use placement agencies to find residents being discharged from nursing homes, other consumer advocates say. OHCQ, having investigated cases in which this practice ended with elderly abuse or neglect, has expressed concern over the potential for problems.

Because there is no comprehensive assisted living home rating system in Maryland, the best a discharged resident needing daily care can do is make sure his or her assisted living home is licensed with the state by checking the state-uploaded PDF file, where all licensees are compiled.

4. An overwhelming nursing home admittance process complicates understanding of rights

What happens when a person enters a nursing home is generally referred to as disorienting, complete with a stack of paper and a “sign here … sign here” urgency.

As required by law, nursing facilities must present a contract consistent with Maryland’s skilled nursing care rights. But the ombudsman reported that due to the volume of papers and general stress of the admittance process, many residents are unaware of their legal resources until they’re issued a discharge notice and need legal counsel.

Additionally, many companies ask incoming patients to sign arbitration clauses, which require that if a complaint comes up, the patient will settle with the nursing home through a third party rather than seek public litigation.

Arbitration clauses are fairly standard practice in the industry, officials said, but Bennett added a caution that consumers should ask about it when being admitted.

“The lesson to the consumer is, if you’re an older adult like I am, don’t wait to learn about nursing homes and assisted living,” Hedt said. “Try to learn about it even before you need it, so that you can make decisions in an emergency if you have to.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.